In particle physics, the so-called “Standard Model” is a flawed yet widely accepted picture of how the universe works—the rules and formulas governing elementary particles like electrons and quarks, the forces holding together atoms and molecules, the theoretical basis of electricity and magnetism. It’s been in development since the Atomic Age in the mid-20th century, continually tweaked and refined but never upended, and it accounts so precisely for so much of what we can observe in the lab that alternative theories are often regarded as exotic, even fringe. For now, it has no serious competitors.

Still, we know that it really can’t be complete or even correct, because it has no way of accounting for the big picture: the force of gravity that tells us which way is up, the mysterious dark matter that holds together galaxies, the accelerating expansion of the universe. It’s a convenient fiction.

When it comes to sex, relationships, and reproduction, something like a Standard Model also exists, and it, too, found a name in the Atomic Age: the Nuclear Family. This supposedly elementary social building block consists of one man and one woman in a sexually and romantically exclusive relationship, typically having children together and raising them in a house until they’re ready to move out and eventually settle down with spouses of their own to repeat the cycle.

In a Nuclear Family, the man has a paid job and brings in money, while the woman runs the household. 1 People (men especially) are defined by specialized work and valued for their individual achievements. Ownership of assets is individual or “joint” (meaning belonging to the couple), and one of life’s main goals is to amass as much wealth as possible. People are free to dispose of their assets more or less as they wish, with their legal children inheriting any remaining loot when both parents die.

Sexual or romantic liaisons outside the exclusive pair bond are verboten. When pursued furtively, they’re a source of both guilt and, if exposed, shame. Any children known to have been born of such an unsanctioned liaison face inheritance challenges and lifelong stigma as “illegitimate” or, to use an older and even uglier term, “bastards.”

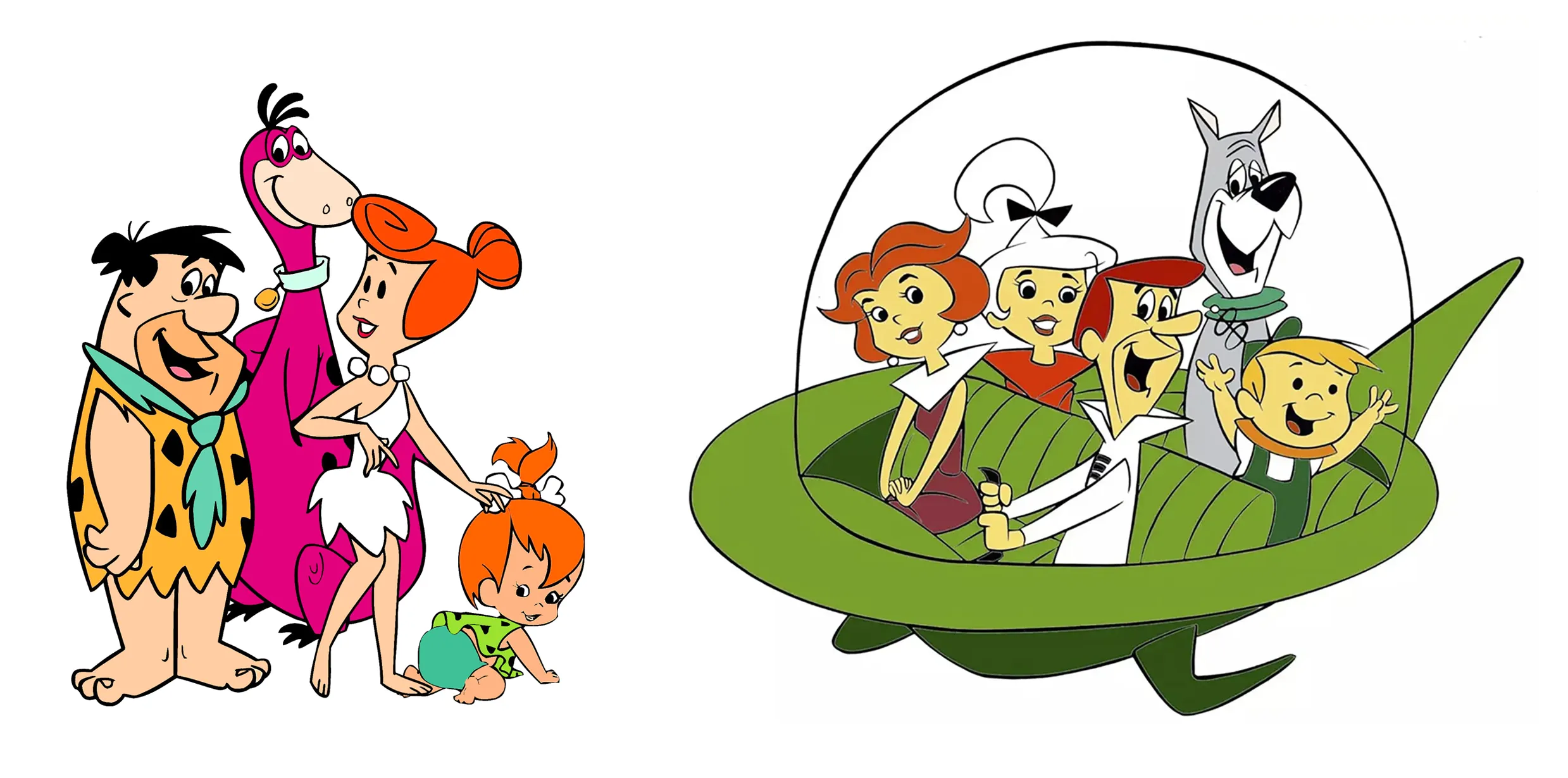

These rules and norms doubtless all sound familiar. Many of us were brought up to think of them as not just familiar, but universal. Whether ironic or not, the endless reruns of Hanna-Barbera cartoons I remember watching—The Flintstones, The Jetsons—embraced the premise that from the Stone Age to the Space Age, however much the technological trappings may evolve, the Nuclear Family has always been and will always be the fundamental unit of human sociality.

Hanna-Barbera cartoons were hardly an isolated case. The edifice of mainstream 20th century media, from Norman Rockwell paintings to Leave it to Beaver sitcoms, all agreed. More broadly, much of Western society was built on the presumption of this kind of domesticity: laws, institutions, customs, entertainment, housing, transportation, jobs, infrastructure, and even—as with handedness—the very language we think with.

Nuclear Families may not be a law of physics, but neither did they come out of nowhere. To understand their underlying logic, we can ask: Why and when did they arise? And what’s really at stake when we start questioning them?

In his 1837 book The Philosophy of Marriage, the physician Michael Ryan summarized the widely held view—especially then, and still today—that the monogamous pair bond underlies not only our entire political economy, but the reproductive future of humanity. There are some obvious wrinkles: the monogamous pair bond is far from universal today, it’s not the historical norm, and it’s “unnatural,” insofar as it doesn’t come easily to many, requiring constant legal, social, and moral enforcement.

I’ll quote from Ryan at length, in the spirit of showing rather than telling:

POLYGAMY, or Polygyny, is sanctioned by laws of eastern nations […]. Although polygamy is interdicted by our laws, it does not exist the less in the hearts of most men who profess to be monogamous, but who are no less polygamous by their actions. […] St. Augustin, Grotius, and other moralists, admit this truth, but declare it would be contrary to morals, the interests of society, and the increase of population. Nevertheless, polygamy, or concubinage, is common among the higher classes in all civilised countries. […] [The] promiscuity of the sexes would be justifiable according to many writers (Pliny, Diodorus, Siculus, &c.), and […] there are some few eastern countries in which a community of women was, and even now is tolerated. […] It is easy to adduce many valid reasons to prove that this community of women, and promiscuous intercourse of the sexes, can never be tolerated in any enlightened country. It must be obvious to the commonest understanding, that without marriage, neither paternity, nor family, nor patrimonial possession, nor division of landed property, nor legitimacy could be accurately determined; and thence it would follow that all would belong to all, every one would be benefitted in common, no one would exert himself for all his race, and the result would be a state of barbarism as in savage nations, and all the laws of society would be overturned.

You read that right: monogamy must be enforced so that capitalism and patriarchy can be preserved! What might an alternative look like? Ryan continues:

This perfect community of women and property, if it could take place, could only exist among people living as savages, and among a very small number on a vast territory. Suppose the community of women was established, what man would willingly allow an infant to be affiliated to him, of which he had any right to doubt that he was the father? The woman would violate the sacred duty of nursing her own infant only, and in a few centuries the human race could not be preserved; there would also be incessant desertions of infants, and a great increase of infanticides, crimes unfortunately too common; even under existing laws, but which would be innumerable in proportion as the people and their morals became more corrupted, and where no asylums would exist for the fruits of universal debauchery. Every fine feeling of paternal and natural love would be destroyed; all cares and protection of children would be at an end, and the mortality would become so great as in a few ages to exterminate the human race. 2

Whew, that’s a lot to unpack!

For starters, Ryan’s curious phrase “community of women” read differently in 1837 than it does today. He didn’t mean a sisterhood or community among women, but that they’d be communally owned—meaning the communal property of men, who are clearly the intended readers here. Ryan would have considered it nonsensical to talk about a “community of men”! So, he can imagine non-monogamy—it looks a lot like communism—but if anything, it’s even more patriarchal than the monogamous alternative, in which a woman “belongs” to one man, rather than to all men. A grim picture.

Despite Ryan’s chauvinism and catastrophizing, there are elements of truth here. Among documented societies, sanctioned polygyny (sexual relationships between one man and multiple women) is a good deal more common than sanctioned polyandry (sexual relationships between one woman and multiple men), 3 and polygynous societies do tend to be highly patriarchal. 4 Also, as we’ll see, a relationship between communism and non-monogamy does exist, both in traditional societies and among the freethinking sexual pioneers advocating “free love” who had begun to spring up in Ryan’s day—much to his dismay.

This passage also reminds us that the 20th century Standard Model had already departed in significant ways from its 19th century precursor (itself a recent invention), mainly due to the slow but steady progress of the women’s rights movement. It wasn’t until the 1848 Married Woman’s Property Act, passed in New York and used as a model in other states, that a married woman could enter into contracts, collect rent, receive inheritances, or enter into lawsuits on her own. 5 Such basic obstacles to independence survived far into the 20th century; until 1974, many American banks required married women’s husbands to cosign any credit application, and in Ireland, women only won the right to own their own homes in 1976. Legally and financially, a married woman in the 19th century really was her husband’s property.

An 1854 critique of marriage by Thomas Low Nichols (1815–1901) and Mary Sargeant Gove Nichols (1810–1884), just the kind of free love activists Ryan was railing against, described the state of marriage in the starkest possible terms:

In the early ages slave and wife were convertible terms. The slave became the wife of her master, the wife no less became his slave. In both cases they were sometimes purchased, sometimes taken captives in war; sometimes they were presents, given as the hostages of peace and friendship. […] The great wrong of slavery consists in the power which it gives to one human being over another. A husband has almost precisely the same power over the wife that the master has over the slave. 6

A century later, this comparison would have been less appropriate; Mary Nichols might have kept her original name, Mary Neal, and she would have been able to vote, sign contracts, and own her own assets, whether married or not. Then again, she was white, educated, and lived in New England. Gender inequalities like those of the 19th century US, and worse, still hold in many parts of the world. In 2017, the International Labour Organization first classified forced marriage as slavery, estimating that nearly 22 million women are thus enslaved. 7 In every country, women’s equality remains very much an incomplete project.

In traditional American marriages with one wage-earner, that earner is still more likely to be the husband than the wife, though the balance has started to shift. 8 Even when a woman works a paying job, her wage is likely to be significantly lower than a man’s. Numbers from the Bureau of Labor Statistics tell the story. 9

Here the dots are raw data from the Bureau, and the lines are smoothed versions to make trends easier to see amid the random year-to-year fluctuations.

On average, women of all ages, from 1979 until 2020 (the year these data were released), earn at most 95% or so of what men earn. Despite gradual improvement over those 38 years, the gap has stubbornly refused to close. To many, like Cris, a woman in her forties from Tennessee, this isn’t news:

I was born on a day that was a huge step forward for womans rights, while my full name indicates female, i have never went by it, nor was I raised with my parents calling me by it. They done this so it would be easier on me in life for the job market.

Women of high school age have been consistently earning about 95% of men’s income for decades, while older women have been catching up to, but never exceeding, that plateau. In dollar terms, incomes are much lower at younger ages, so even those modest gaps for 16- to 24-year-olds can make the difference between being able to scrape by on their own and not. Among older people making more money, the differences become far greater, both in dollars and in percentages. If you were a 50-year-old woman earning an average wage in 1979, that amounted to less than 55% of what the average 50-year-old man earned. By 2020 the figure had risen to about 80%—an improvement, but still not great.

Now, consider this difference in terms of accumulated savings, with compound interest, over a lifetime; you’ll start to appreciate why women have so much less wealth at retirement than men, and fall below the poverty line at far higher rates. 10

Such considerations would have strongly incented a young Wilma to marry Fred Flintstone, even if she worked full-time and wasn’t all that into him. Of course people can remain in less-than-happy marriages for many reasons. Money and motherhood tend to curtail women’s choices disproportionately, though. When Wilma’s baby came along, the case for keeping her Nuclear Family together might strengthen, given the primary role mothers play in providing for their children. Was Fred shouty and unhelpful—abusive, even? Did he spend his weekends reclining on the La-Z-Boy watching football? Did he get caught messing around with Betty next door? In a patriarchal world, there are still hard economic realities. Alimony notwithstanding, 11 many unhappy wives have stayed married for the kids’ sake, or because there was simply no viable alternative.

Despite these powerful social forces, the Standard Model for US families has never been as universal as it was made out to be on TV—with working moms, grandparents, and other relatives living under the same roof, communal arrangements, children moving back in after college or never moving out in the first place, divorce and blended families, adoption and surrogacy all commonplace. For that matter, it’s hard to ignore the whiteness, suburban-ness, and middle-classness of this supposed standard. In the Antebellum South, the “standard” certainly didn’t apply to the enslaved population; nor have Black, Native, and immigrant communities of later generations necessarily fit the mold.

The mismatch with reality goes beyond minority and immigrant populations in the United States today. Confronted with a wealth of historical evidence from still-extant traditional societies, researchers working at the intersections of evolutionary biology, psychology, economics, and anthropology have finally begun to realize how peculiar the Nuclear Family really is.

Traditional societies, which is to say, nearly all societies until recently, tend to be built instead around clan structures, with high rates of cousin marriage continually reinforcing extended kinship networks. The old-fashioned phrase “kith and kin” is sometimes used, emphasizing that these networks include both genetic relatives, or kin, and so-called “fictive kin,” or “kith.” (If you had “uncles” or “aunties” as a kid who were in fact not related by blood or marriage, these were kith.) Such social networks are at once stable and fluid, meaning that dense interconnectedness maintains a sense of belonging and community stability even as people occasionally join or wander off to seek their fortune elsewhere.

How does family life work in such a setting? Anthropologist and primatologist Sarah Blaffer Hrdy has convincingly argued that much of what makes humans special (and unique among the great apes) is made possible by alloparenting—our habit of caring for each others’ young—and in particular cooperative breeding, in which the babysitters aren’t themselves mothers; they may be young or post-menopausal females, or males. 12 Our survival likely depended on alloparenting for hundreds of thousands of years, since in a traditional society, it’s extremely difficult for a mother alone to procure the thirteen million calories needed to raise a child to maturity. It helps to have dads, grandmas, and friendly neighbors bearing snacks.

And not just snacks. Humans are born helplessly inept. Unlike other animals with more complete (though also more limited) instinctual behavioral repertoires, we must learn a great deal from others to become self-sufficient. This requires an investment in time and mentorship from multiple adults, older siblings, cousins, and so on. Raising children truly does take, if not a village, at least a committed social network of helpers.

Hrdy also points out a related, darker finding: “Along with humans, marmosets and tamarins are virtually the only primates where mothers have been observed to deliberately harm their own babies or leave newborns to die.” 13 As it turns out, these species also stand out as the most cooperative breeders among our primate cousins. The mothers tend to commit infanticide when they know they won’t have the community support they need to raise their offspring successfully.

Consider the high rate of infanticide and baby abandonment that so horrified Michael Ryan (the pearl-clutching author of The Philosophy of Marriage) in this light. The 18th and 19th centuries saw a dramatic rise in these practices throughout Western Europe. 14 The rise coincided with the start of a great migration of people away from a more traditional life in the countryside and into cities, far from kith and kin. Those cities, in turn, did not yet provide anything like the state assistance, food banks, social services, daycare centers, kindergartens, and so on that might have taken up the alloparental slack for the displaced poor.

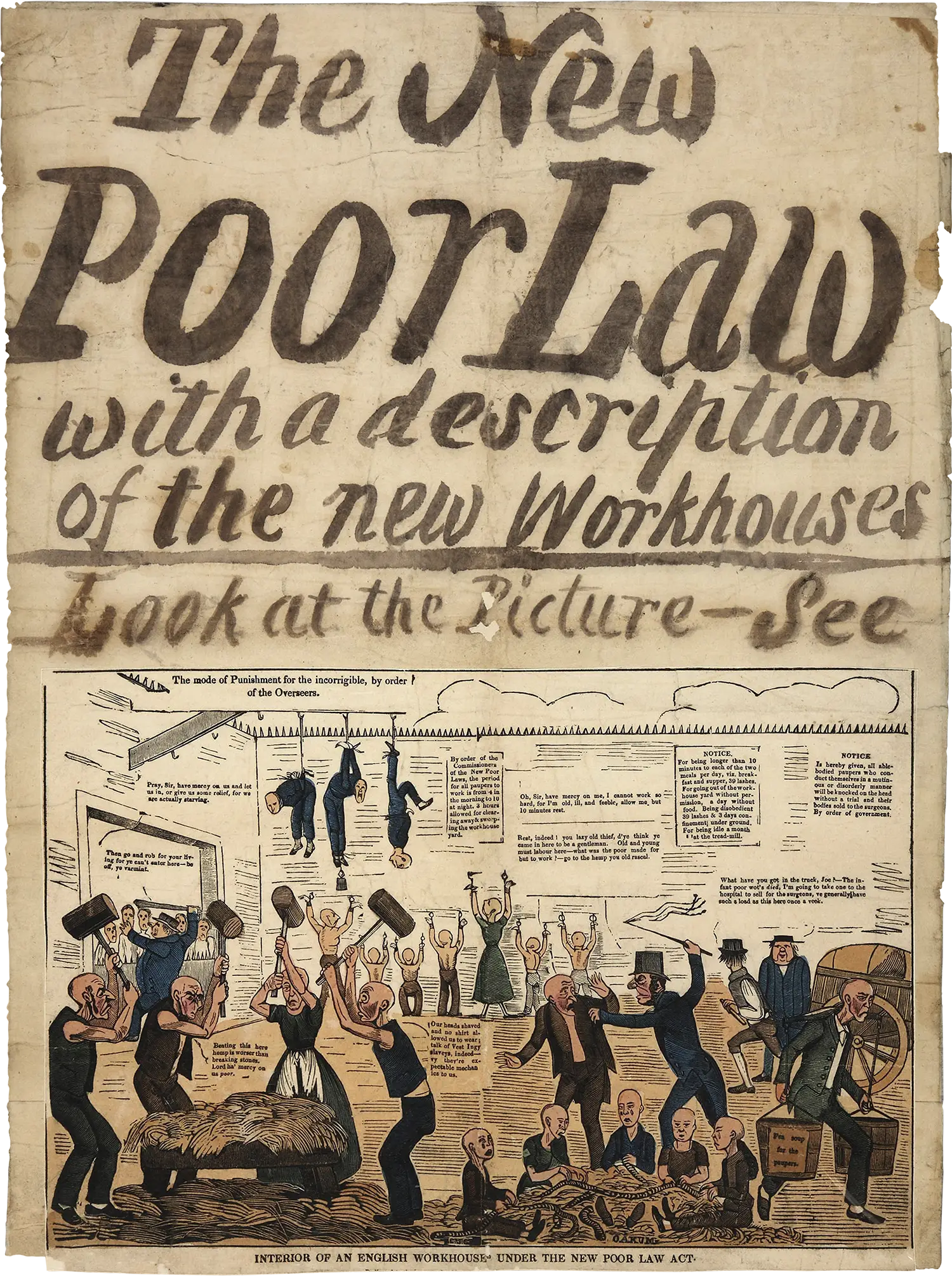

The English Poor Laws were important steps toward organized state assistance, but gave rise to Victorian-era workhouses designed to be punitive, with revolting food, forced family separation, and other disincentives making life in such an institution a last resort. Since poor working people were already immiserated, ensuring that the workhouse remained strictly worse often meant truly grim conditions.

Ryan likely had it backwards, then, when he claimed that free love communes would result in wholesale infanticide. It was the rapidly industrializing, capitalist, and Nuclear Family-oriented London of his day that did so.

In traditional “kith and kin” societies, where extended relationship networks are paramount, individualism plays a more modest role than in modern urban life. Work tends to be less specialized. As we’ve seen, child rearing is a collective effort. Housing and property ownership (when they exist) are often collective too, and are usually controlled by men—patriarchy being perhaps the one Flintstones-Jetsons motif that does have a long history.

Such patterns persist even in the lives of white city-dwelling Westerners today, and are especially evident in the (underrepresented) accounts of the contemporary poor and working class. For instance, English activist and author D. Hunter writes in his 2018 autobiography, Chav Solidarity,

As a seven year old I was shown how to be a lookout during a robbery, and not long after, my cousins taught me how to steal a car. All of the rewards for this were collectivised […]. One of my uncles was fiercely respected for the amount of money he brought into our family, but he lived in a one bedroom flat which was furnished with a mattress, a TV and nothing else. I only have a thin recollection of the flat but I’m not convinced it had a bathroom. This was acknowledged, but never challenged, it was raised by others as an example of how we all should be. […] The money went to uncles and aunts with children instead, so that those kids wouldn’t go short. […] My grandfather took whatever he wanted from the collective pot, and I’m sure he would say, that as the responsibility for everyone else was with him, it was only right. […] If one of my cousins was given something, they would share it without a second thought. Nothing was saved for later; nothing was personal property. 15

When a dominant society enforces norms and creates institutions at odds with the traditional cultures of families like Hunter’s, those families tend to be marginalized. Often, they live in undocumented ways and outside the law, rendering the underlying structures that have organized their lives for countless generations invisible to outsiders. They might get by mainly with cash, in a black- or gray-market economy. Many of the resources cities offer their middle classes become harder for such communities to tap into, locking them into cycles of intergenerational poverty. Schools, governments, banks, potential employers, and social services demanding that forms be filled out (parent or guardian, permanent address, occupation, income, etc.) require semi-fictional responses.

Similarly, while legal marriages do exist, the many and varied intimate relationships and sexual encounters Hunter recounts often don’t occur within them, or within any of the parameters considered socially or even legally acceptable today. They certainly don’t follow the monogamous Nuclear Family model.

Non-monogamous sexual relationships (meaning, anything outside a sexually exclusive long-term pair bond) are also the norm in traditional societies, whether settled, nomadic, or somewhere in between. The specifics vary widely, but tend to be more fluid and less patriarchal among hunter-gatherers or other societies with temporary (often seasonal) settlements.

Nomadic or seasonally settled societies are also less dependent on property ownership. In such settings, polyandry may be a good idea: a mother’s vagueness about the paternity of her children won’t cost them an inheritance, but might offer a fine strategy for expanding the network of alloparents (including potential fathers and their kin—a bonanza of indulgent aunties, uncles, and grandparents). 16

In traditional agricultural societies, though, land and livestock tend to be owned by men. Fixed settlements of varying grandeur can be built on that land, and the labor needed to farm it can itself become a commodity. Then, patriarchy tends to predominate. Number of wives, as much as access to land, livestock, and labor, signifies a man’s social rank, and since assets pass from fathers to sons, paternity is all-important. Given roughly equal numbers of women and men, many women end up sharing a high-status male partner, while large numbers of lower-status men remain single. Some version of this more patriarchal traditional model still holds in many places today.

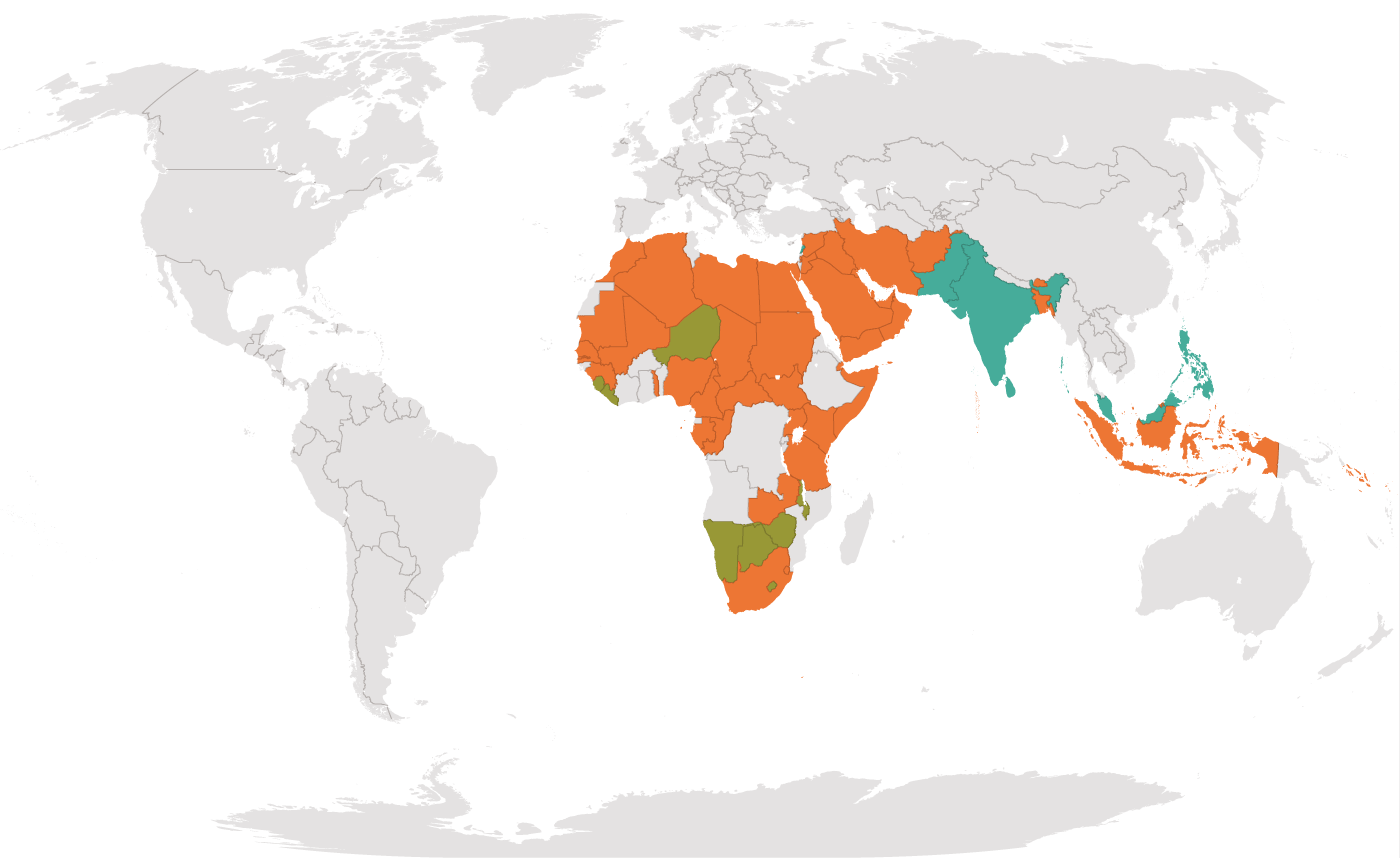

So where did Nuclear Families come from? Joseph Henrich, chair of the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology at Harvard, argues that they’re a defining feature of what he memorably calls WEIRD societies: Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic. 17

Monogamy and the suppression of cousin marriage, both key to establishing the Nuclear Family model, were Christian religious policies, advanced with varying success throughout Europe in the Middle Ages as natural laws and expressions of God’s will (despite numerous Biblical counterexamples 18 ). These policies had profound economic and political consequences. As a somewhat cynical 26-year-old survey respondent put it,

I do not believe in monogamy or marriage. I believe they are created by those in power (government and religion) to keep people under control. The government needs couples to buy homes, create children and keep the economy humming. And religion uses marriage and monogamy for power, control and access to money.

While there’s a whiff of conspiracy theory about the way this is put, it’s… not wrong. (Though of course non-monogamous arrangements have their own politics, and their own ways of perpetuating power.)

Beyond offering avenues for social control by the church or the state, though, WEIRD societies foster social stability in other ways. Several lines of evidence suggest that large numbers of unpartnered males with little to lose drive higher rates of violence and instability in traditional societies, which might be one reason that enforced monogamy created a competitive advantage for the WEIRD.

A Christian belief in the universality of God’s strictures may have kept most Westerners from realizing how unusual their Nuclear Family model was, even when, as with the Flintstones and Jetsons, Christianity wasn’t overt. Or maybe it was hard to notice how atypical this model was simply because the worldwide influence of WEIRDness has grown so pervasive over the past several centuries.

Scientific research, technology, political power, and wealth are all overwhelmingly WEIRD-dominated today. 19 WEIRD media, social norms, and psychology have also infused many other societies globally, both through imposition from outside (which we might call cultural hegemony), and through voluntary copying, appropriation, or local adaptation, as humans have always done. These phenomena have all created feedback loops, perpetuating and reinforcing each other. Still, it’s important to remember that WEIRD people remain a minority, and represent a small fraction of humanity historically.

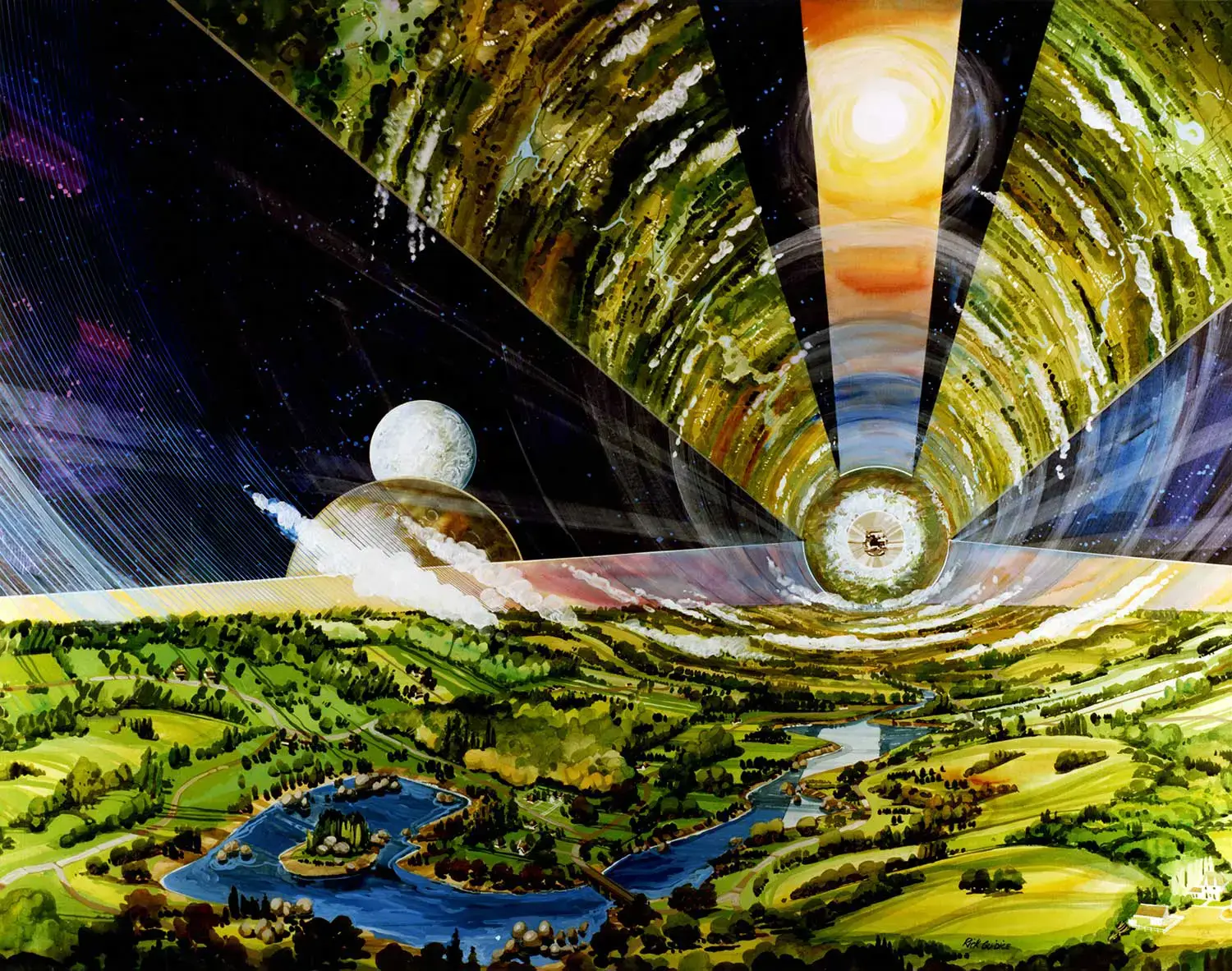

The real Flintstones, then, were decidedly not WEIRD; Paleolithic people’s daily lives wouldn’t have made for family-friendly TV in 1960s America. But what about the Jetsons?

Let’s assume a non-dystopian scenario in which future generations are at a minimum educated, industrialized, and rich (“EIR”). Even so, far from being a universal norm, the Nuclear Family may turn out to be a short-lived historical footnote, a transitional step between a “kith and kin” past and an emerging model whose outlines we can just start to make out.

What are those outlines? That’s one of the central questions Part II of this book will attempt to answer. Chapter 5 focuses on emerging patterns in romantic and sexual exclusivity—in a way, the least radical of the changes we’ll explore, since this exclusivity has always been preached more than practiced. In Chapters 6 and 7, we’ll take a closer look at the decline of heteronormativity, the force that binds Nuclear Families together, and in Chapters 8 and 9, we’ll delve into the implications for (and about) women’s sexuality. Finally, in Chapters 10 to 15, we’ll see how biology and culture are interacting to redefine sex and gender.

Today, many people aren’t romantically or sexually exclusive; aren’t having children, or are approaching parenthood in different ways; aren’t heterosexual; aren’t as reliant on property ownership; and aren’t living in either multigenerational or nuclear households. Even conservative columnist David Brooks knows something is up; his 2020 think piece in the Atlantic, “The Nuclear Family Was a Mistake,” points out that it has been “crumbling in slow motion for decades.” 20 Feminist writer Sophie Lewis goes further in a 2022 book, spicily entitled Abolish the Family. 21 To her, as journalist Marie Solis writes, the call for abolition means “caring for each other not in discrete private units (also known as nuclear households), but rather within larger systems of care that can provide us with the love and support we can’t always get from blood relations […].” 22

Increasing numbers of people are also questioning, tweaking, or entirely discarding the gender binary that has underpinned both the Nuclear Family and earlier, more traditional social structures. Gender Abolition, too, is an old social movement now gaining mainstream traction.

Though historical context can help us find antecedents to, and make sense of, these trends, they’re far from a return to a preindustrial past. They represent something new.

But how new? Seen from a certain perspective, changes to family, sex, and gender can have radical, even posthuman overtones. Science fiction writers like Octavia Butler, Pat Cadigan, Justina Robson, Annalee Newitz, and Kim Stanley Robinson have imagined futures in which gender is just one of many fluidly alterable bioengineered variables for our descendants… who may also range from three to ten feet tall, splice in the DNA of other species, merge with robots, and adapt themselves to live anywhere from the dark side of Mercury to the moons of Saturn. 23 Human lifetimes may become unconstrained by any inbuilt biological clock; babies may become rare, and may be grown in artificial wombs.

Even these versions of posthumanity are conservative compared to “uploading,” in which we all scan our brains and become virtual beings, unmoored from bodies or the constraints of the physical world. What could human or personal identity even mean in a universe like that?

Imagining such futures can induce a kind of vertigo, even horror. Then again, our lives would be equally alien to our recent ancestors. It helps to remember that we humans are a uniquely culturally constituted species. So much about our lives and bodies is already a product of our cumulative culture and technology—from our lack of fur (due to the invention of clothes) to our short gut (due to cooking with fire) to our ability to drink milk in adulthood (still a work in progress, or if we all end up vegan, an evolutionary spur). 24

In this sense, we’re already highly engineered, and we have ourselves been the unwitting engineers. Profound culturally induced changes in gender and sexuality may, then, just be the next steps on a long road we began walking millions of years ago when we tamed fire, our brains began growing rapidly, and cultural development began to snowball over generations, radically reshaping not only our bodies but Earth itself.

The “man alone is the breadwinner” aspect is the most dated, but disparities in income continue to cast a long shadow, as we will see.

Ryan, The Philosophy of Marriage, 91–93, 1837.

Starkweather and Hames, “A Survey of Non-Classical Polyandry,” 2012.

White and Burton, “Causes of Polygyny: Ecology, Economy, Kinship, and Warfare,” 1988; McDermott and Cowden, “Polygyny and Violence Against Women,” 2015.

McCammon, Arch, and Bergner, “Early US Feminists and the Married Women’s Property Acts,” 2014; Chused, “Married Women’s Property Law: 1800-1850,” 1982.

Nichols and Nichols, Marriage: Its History, Character, and Results, 91–92, 1854.

International Labour Organization, Walk Free, and International Organization for Migration, “Global Estimates of Modern Slavery: Forced Labour and Forced Marriage,” 2022.

Pew, “The Rise in Dual Income Households,” 2015.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Highlights of Women’s Earnings in 2020,” 2022.

Inequality.org, “Gender Economic Inequality.”

In 2001, only 52% of divorced mothers in the United States received their full child support payments. For women who had children out of wedlock, the figure was about 32%. These data are per Dominus, “The Fathers’ Crusade,” 2005.

Hrdy, Mothers and Others: The Evolutionary Origins of Mutual Understanding, 2009.

Hrdy, 99.

Fuchs and McBride-Schreiner, “Foundlings and Abandoned Children,” 2014.

Hunter, Chav Solidarity, 2018.

Ryan and Jethá, Sex at Dawn: The Prehistoric Origins of Modern Sexuality, 2010.

Henrich, Heine, and Norenzayan, “The Weirdest People in the World?,” 2010.

The Old Testament is full of patriarchs and kings with multiple wives, including Esau, Abraham, Jacob, Elkanah, David, and Solomon. Exodus 21:10 advises that if a man takes another wife, then of the first one, “her food, her raiment, and her duty of marriage, shall he not diminish”; Deuteronomy 21:15–17 clarifies the rules of inheritance for sons in polygynous marriages.

China is now poised to surpass the West in a number of ways, and lacks the “D” as well as the “W,” though significantly, during its “modernization” in the 20th century, it systematically adopted a number of WEIRD social norms and concepts, as did many other countries.

Brooks, “The Nuclear Family Was a Mistake,” 2020.

Lewis, Abolish the Family: A Manifesto for Care and Liberation, 2022.

Solis, “We Can’t Have a Feminist Future Without Abolishing the Family,” 2020.

Robinson, 2312, 2012.

Pagel and Bodmer, “The Evolution of Human Hairlessness: Cultural Adaptations and the Ectoparasite Hypothesis,” 2004; Wrangham, “Control of Fire in the Paleolithic: Evaluating the Cooking Hypothesis,” 2017; Leonardi et al., “The Evolution of Lactase Persistence in Europe. A Synthesis of Archaeological and Genetic Evidence,” 2012.