Yclept is an Elizabethan word, one form of the past participle of to clepe, meaning to name, to call, or to style. […] Ycleptance means the condition or experience of being classified, branded, labeled, or typecast. It has its phyletic basis in likeness and unlikeness between individual and group attributes. Human beings have named and typecast one another since before recorded time. The terms range from the haphazard informality of nicknames that recognize personal idiosyncrasies, to the highly organized formality of scientific classifications or medical diagnoses that prognosticate our futures. The categories of ycleptance are many and diverse: sex, age, family, clan, language, race, region, religion, politics, wealth, occupation, health, physique, looks, temperament, and so on. We all live typecast under the imprimatur of our fellow human beings. We are either stigmatized or idolized by the brand names or labels under which we are yclept. They shape our destinies. 1

Near noon, Janet awoke with a throbbing head, a roaring in her ears, and a wet feeling under her nose. She touched it: bright blood. It had stained the pillow. On the bedside table, the torn-open packet of Aspros she’d swallowed the night before, and the empty water glass she’d used to chase all those bitter pills down. Staggering to her feet, she found her face in the mirror, a dusky red. She turned on the tap and vomited, unexpectedly filled with wonder and delight, thankful still to be alive.

By Monday morning, she was feeling better, just a slight headache. She decided she’d have to give up teaching, a commitment that had been weighing her down with crippling anxiety. The problem wasn’t the children, whom she loved, but the adults—being scrutinized by the headmaster, dealing with the parents, facing the dreaded afternoon tea with the other teachers. How they all stared at her!

Being a student at the University was easier going, more anonymous. It played to her strengths. For an assignment in her psychology course, she was supposed to submit a short autobiography. Self-disclosure came far more naturally in written sentences. As she wrapped the essay up, Janet added, “Perhaps I should mention a recent attempt at suicide,” and described what she’d done, although to make the attempt more impressive, using the chemical term for aspirin—acetylsalicylic acid.

This got the handsome young lecturer’s attention. He asked her to stay after class.

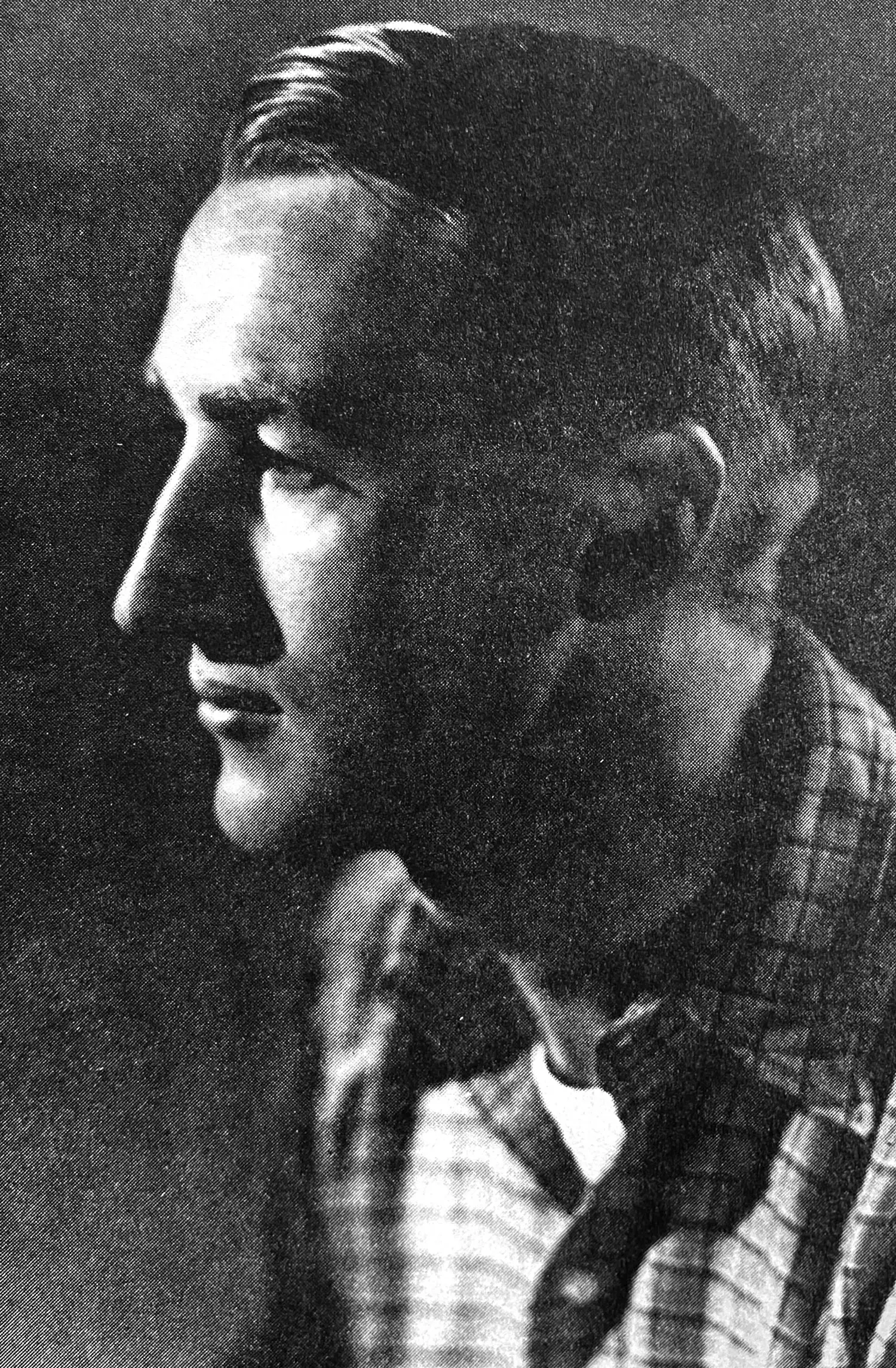

Janet’s family were working class folk from the country. Though barely three years her elder, John Money exuded all the charm, confidence, and worldliness she as yet lacked. A bit of a heartthrob, really, and quite aware of it. He played the piano beautifully, bantered easily with the students about music and books, and dressed flamboyantly, in tomato-red socks and a rust-colored sports coat. In her head, Janet had nicknamed him Ash, after Ashley, the fair young man in Gone with the Wind, played by Leslie Howard.

“I enjoyed your autobiography,” he said. “All the others were so formal and serious but yours was so natural. You have a talent for writing.”

Janet may have felt a flush rising. “Oh I do write. I had a story in the Listener—.” He was impressed. The Listener was hard to get into.

That evening, Mrs. T, her landlady, answering a knock on the door, called up to her, “There are three men to see you. From the University.” And there they were: John, another young lecturer, and the head of the psychology department.

The department head spoke first. “Mr. Money tells me you haven’t been feeling very well. We thought you might like to have a little rest.”

“I’m fine, thank you,” answered Janet.

But he insisted, “We thought you might like to come with us down to the hospital—the Dunedin hospital—just for a few days’ rest. John will come to visit you.”

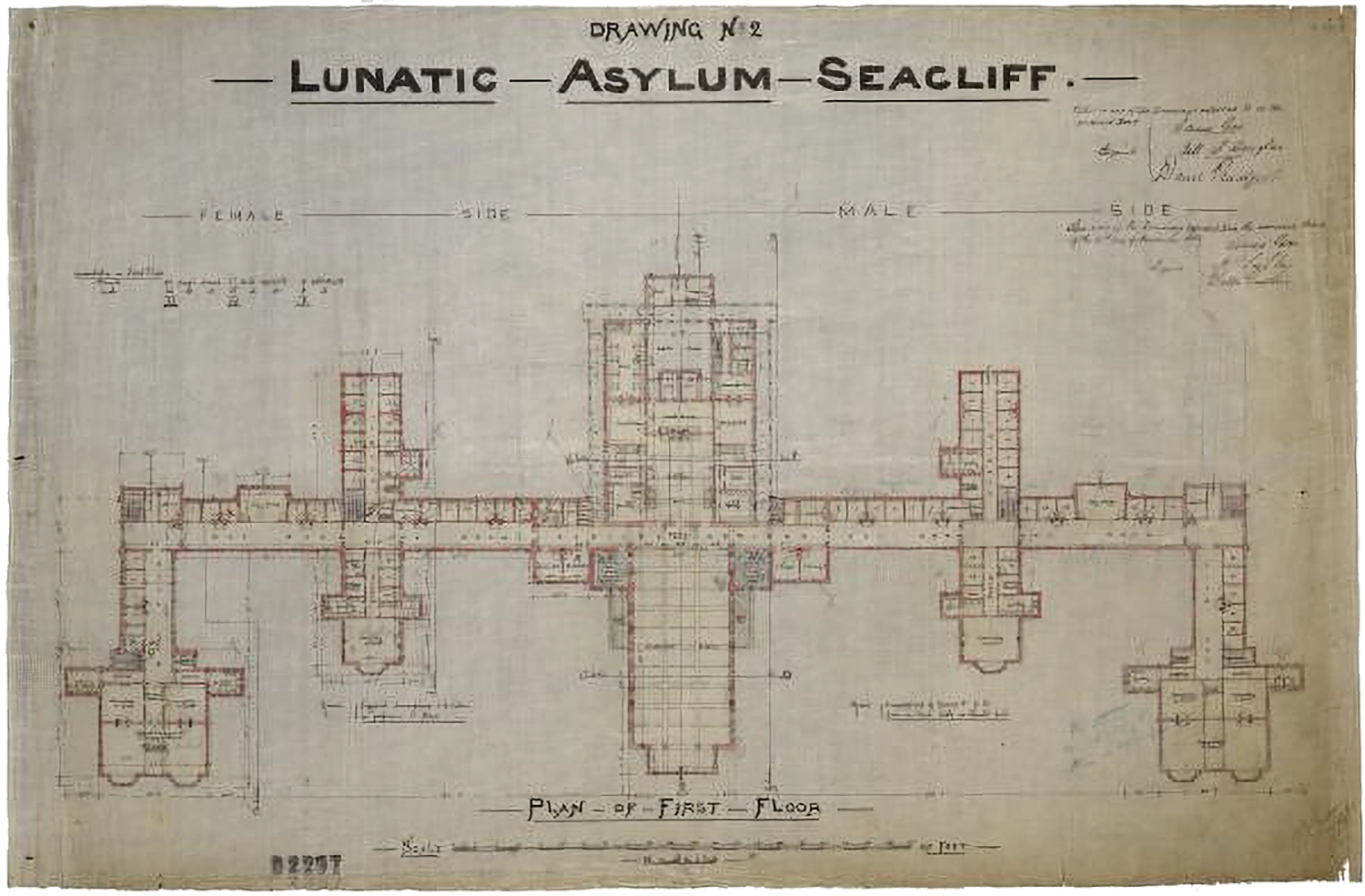

Thus began eight years in and out of New Zealand mental wards, where Janet Frame, who would eventually be shortlisted for the Nobel Prize in literature, was (incorrectly) diagnosed with schizophrenia. She underwent the insulin and electroconvulsive shock therapies popular at the time. After being given the “new electric treatment” at Sunnyside Mental Hospital, as she wrote in her autobiography many years later,

[…] suddenly my life was thrown out of focus. I could not remember. I was terrified. I behaved as others around me behaved. I who had learned the language, spoke and acted that language. I felt utterly alone. There was no one to talk to. As in other mental hospitals, you were locked up, you did as you were told or else, and that was that. 2

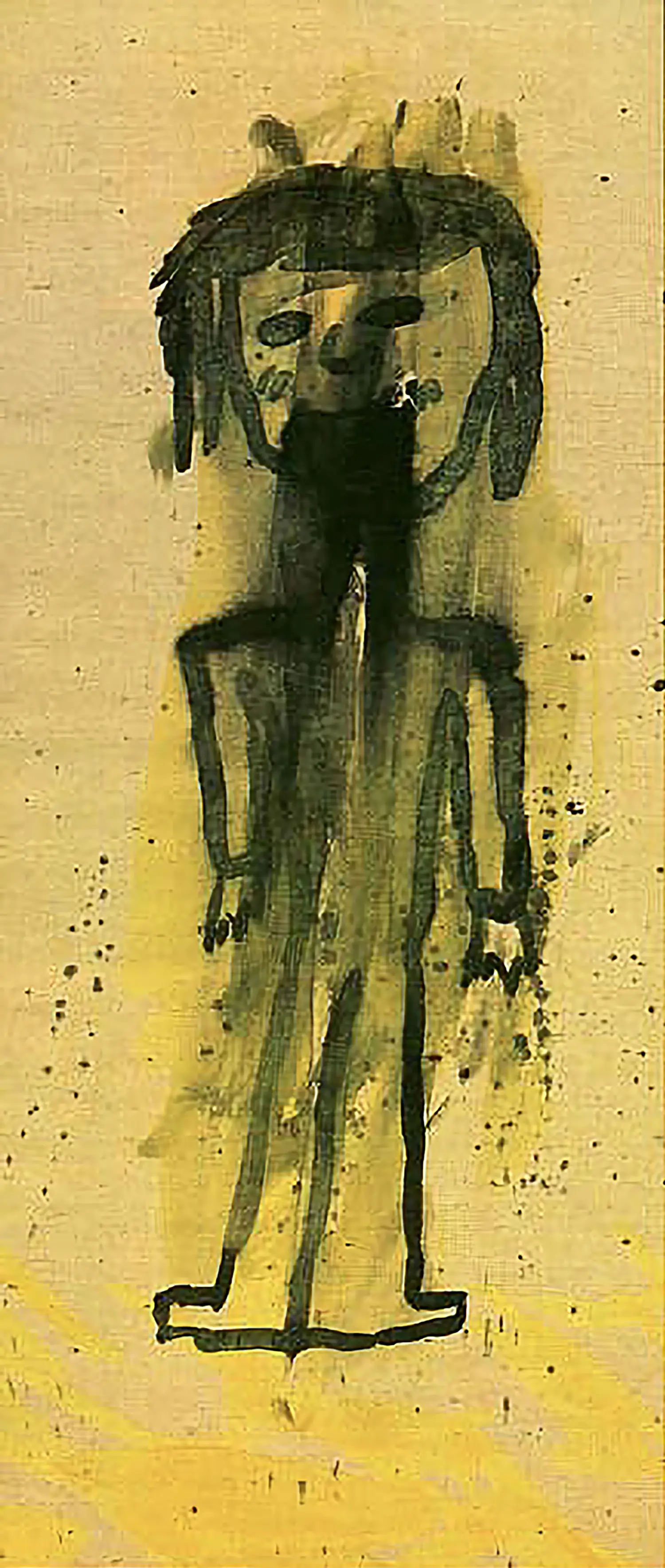

Throughout much of this period, though, she did have one person to talk to. Fascinated by her, both professionally and perhaps in other ways, John Money visited regularly. When he learned that she was writing stories and poems, he suggested that she bring them to their therapy sessions for him to keep. He had all the instincts of a great collector, both of art and of people. At some point he showed her stories to Denis Glover of the Caxton Press in Christchurch, who expressed interest in publishing them in a book, with the poems perhaps following.

Though painfully shy and socially anxious, her hand always in front of her mouth to conceal her rotten teeth, Janet craved John’s attention and praise. Playing up to his expectations, she tailored her symptoms—and her writing—to the case histories she was reading, keeping the “pure schizophrenia” for the poems, where it was “most at home.” There was a dark glamor in the diagnosis. “When I think of you,” said Money, “I think of Van Gogh, of Hugo Wolf.” Looking up these unfamiliar names, Frame found that “all three were named as schizophrenic, with their artistic ability apparently the pearl of their schizophrenia. Great artists, visionaries… My place was set, then, at the terrible feast.”

One day, while perusing case histories, Janet read about a woman who was also afraid to visit the dentist, though in her own case, the reluctance was mainly borne of poverty. However, fear of the dentist was apparently common among schizophrenics, which, “in the Freudian manner … [was] interpreted as guilt over masturbation, which was said to be one of the causes and a continued symptom of schizophrenia!” Money, “glistening with newly applied Freud,” pounced on Frame’s ersatz confession of lifelong guilt, hastening to reassure her that masturbation was “perfectly all right, everyone did it.” Was that a gleam in his eye? Well, certainly, she was doing it now too, although she had only learned how in the course of her furtive reading a few weeks earlier. Better late than never!

By the end of 1946, Janet was once again living in a boarding-house in Dunedin, her state of mind in fragile equilibrium. But then, John let her know that the “little talks” she so treasured would soon be coming to an end, for he had applied to the Psychiatric Institute at the University of Pittsburgh, and planned to emigrate to America. She tried to conceal her sense of betrayal in the wake of his blithe announcement, and her embarrassment over the asymmetry of their relationship. It hurt.

Perhaps grasping for something consoling to offer, he recommended a therapist friend in Christchurch, who, being of an artistic temperament, was interested in Janet’s case. It was an awkward referral, as Christchurch was many hours away by train. But, having no reason now to stay in Dunedin—her abusive family nearby was hardly a draw—Janet resolved to move there. It might make a fresh start.

Soon, she stood waiting on the platform with her few possessions, little more than a folded-up reference from Mrs. T in her pocket (“Polite to the guests at all times, industrious, a pleasure…”) and a tiny black kitten, supposedly male but actually female, whom she had first named Sigmund, then corrected to Sigmunde, and finally shortened to the gender-ambiguous Siggy.

After a couple of years’ study at the Psychiatric Institute of the University of Pittsburgh, John Money went on to Harvard for a doctorate in Psychology, submitting the dissertation Hermaphroditism: An Inquiry into the Nature of a Human Paradox. His career began to take off. Before even being awarded his PhD in 1952, he had already assumed a professorship in pediatrics and medical psychology at Johns Hopkins, a position he would hold onto until his death in 2006. Although his interests were broad and interdisciplinary—some would say unruly—much of his work focused on sexology, endocrinology, and, especially, intersexuality.

He became a giant in his field. The Psychohormonal Research Unit he founded soon after arriving at Johns Hopkins set the standard for the understanding and treatment of trans and intersex people for decades. Money’s name is on about 2,000 articles, books, chapters, and reviews; he received dozens of prestigious awards and honors in his lifetime.

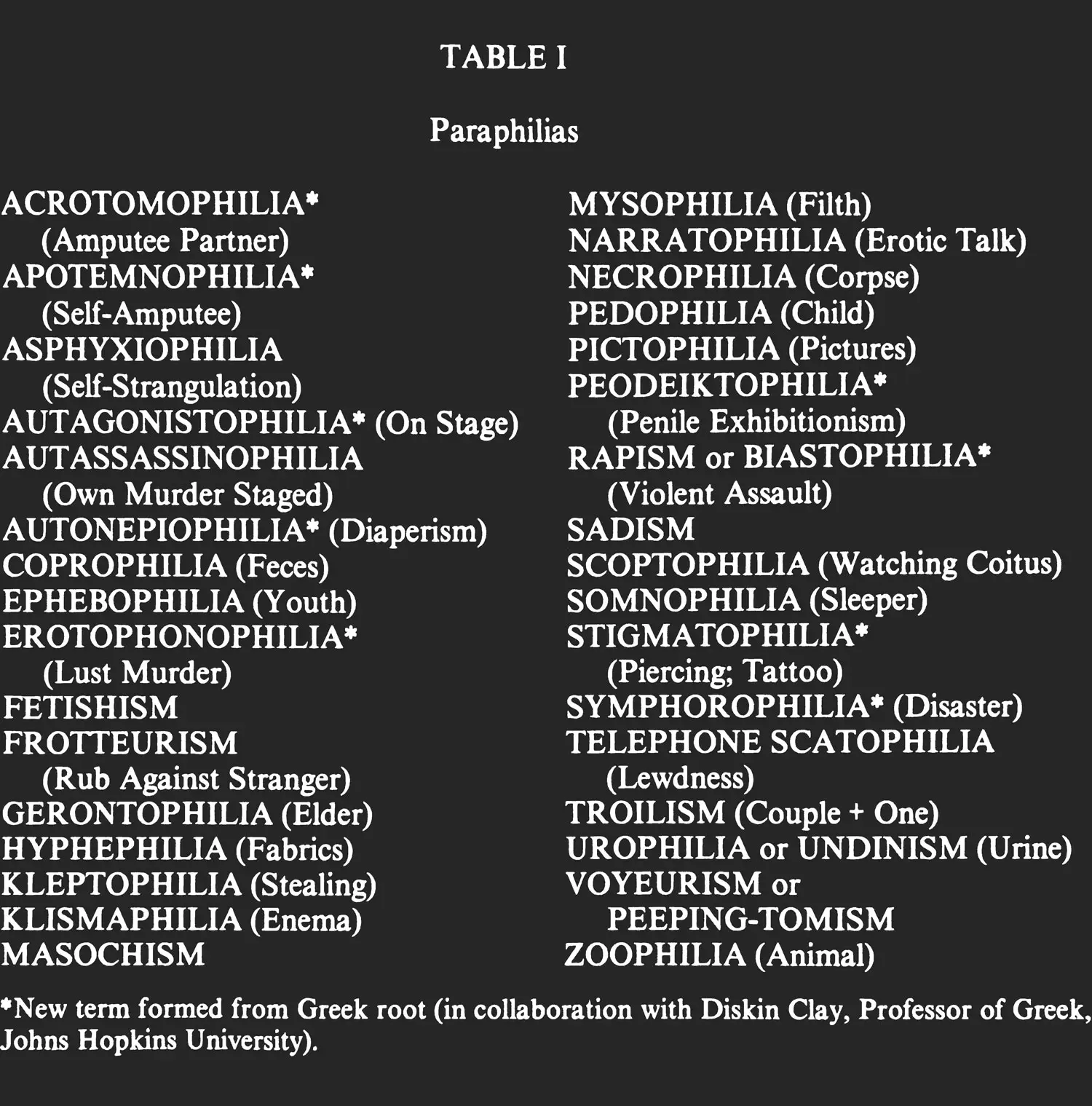

He was a prolific coiner of words and phrases, too. Some, like “foredoomance,” “behavioron,” “gynemimesis,” and “ycleptance,” never caught on; nor did his own name for his favorite subject: “fuckology.” But other terms, like “sexual orientation,” “gender role,” and “gender identity,” have insinuated themselves into everyday English so thoroughly that they no longer sound made up. The word “gender” itself, in its modern usage, owes much to him. Money was the Shakespeare of sexology.

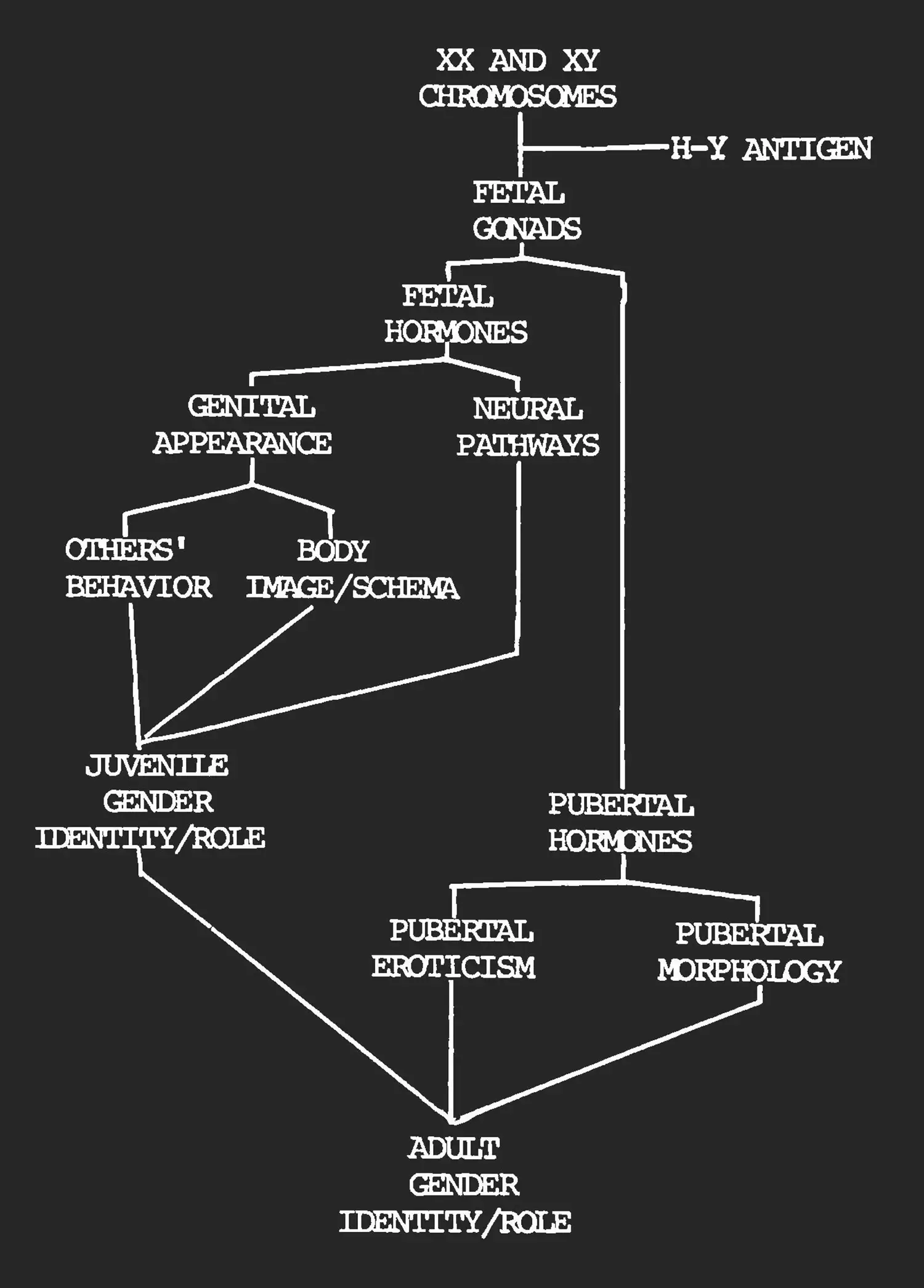

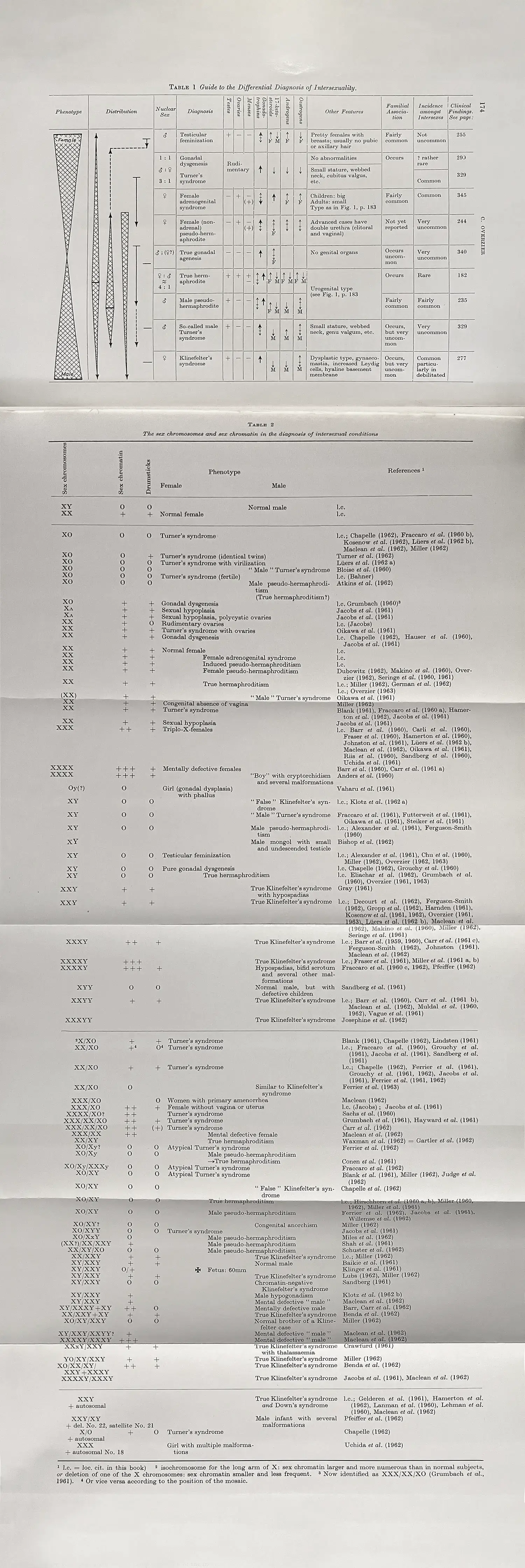

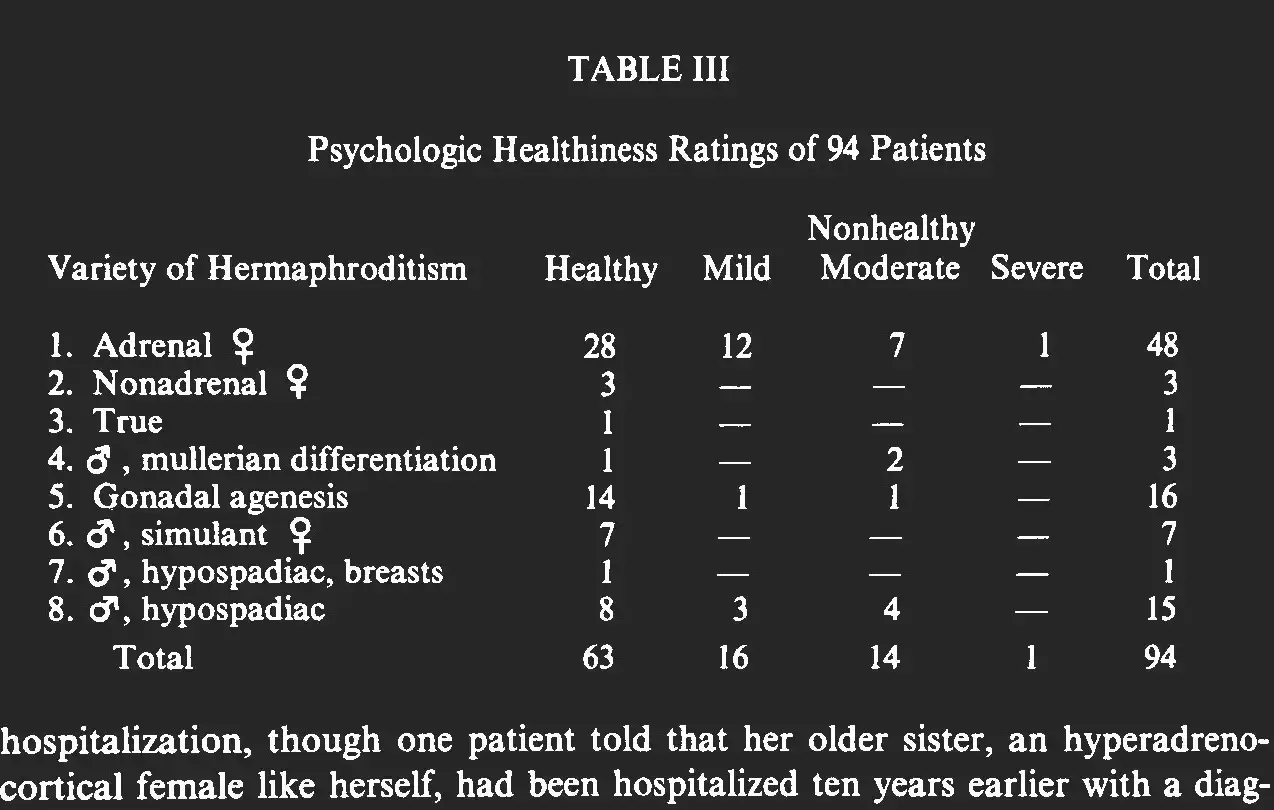

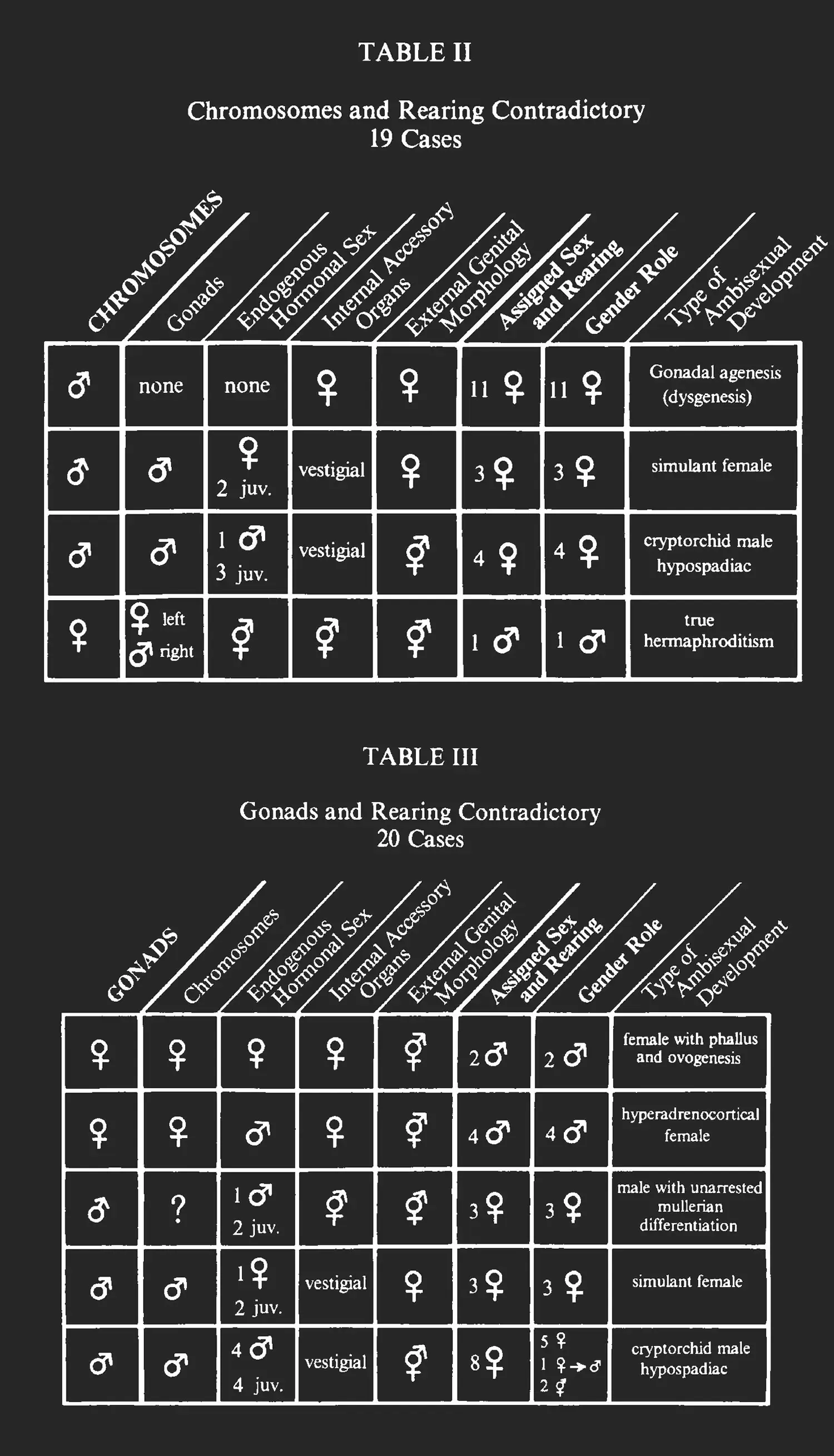

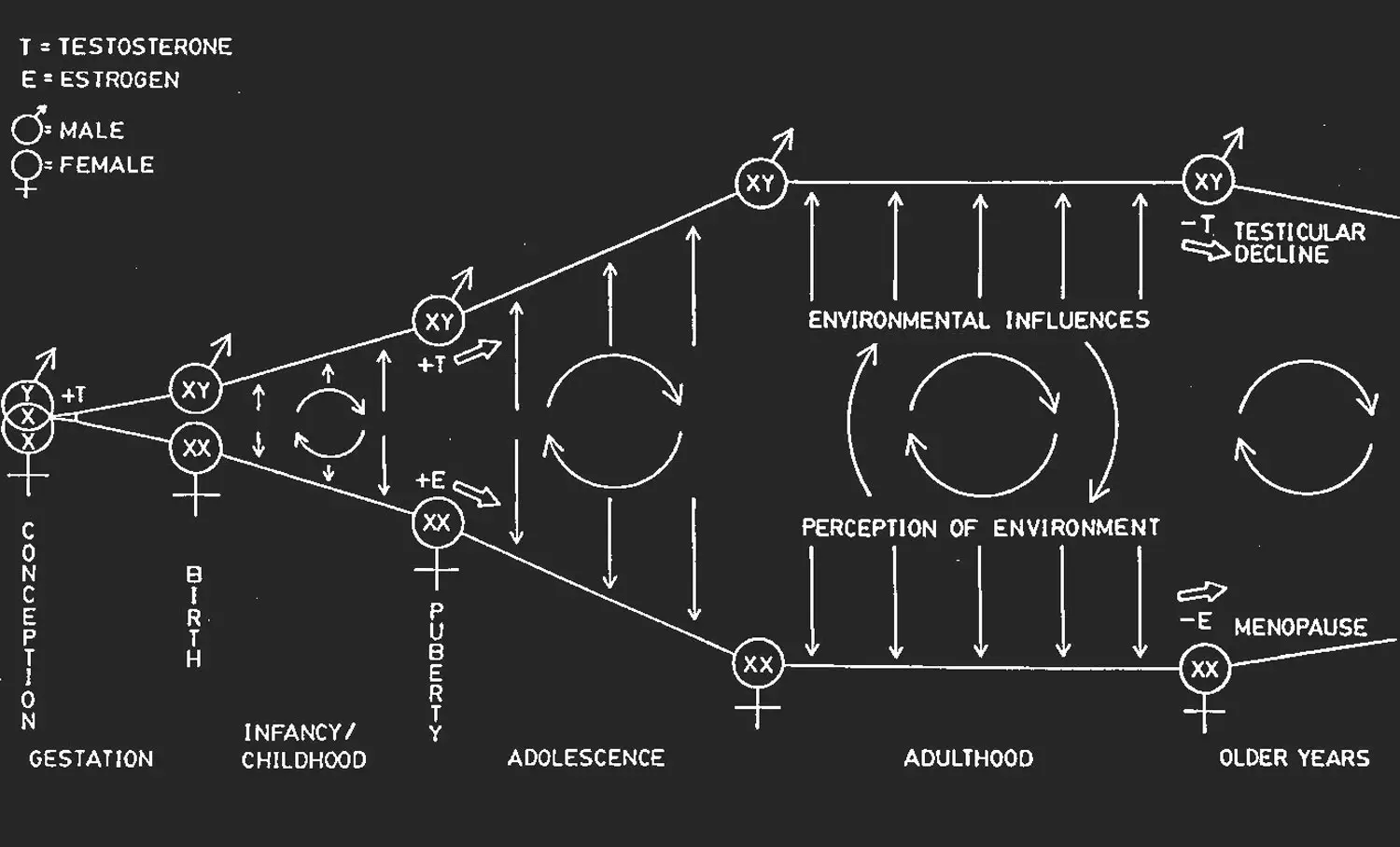

His framework for thinking about sex and gender was sophisticated for the time, synthesizing a wealth of new medical and psychological findings into a coherent theory. Like the Gaian ideas of James Lovelock (and, for that matter, Oberon Zell), it was powerfully influenced by cybernetics, the new science of complex dynamical systems and feedback. Money and his colleagues realized that while most of us think of each individual as intrinsically “male” or “female,” in reality there are many variables working in concert to establish “maleness” or “femaleness,” with a tangle of causal connections and nonlinear feedback loops linking them all together. There are chromosomes, of course. Then, there are gonads (meaning ovaries or testes), which begin as undifferentiated “sex glands” but, once differentiated, are made up of tissue that looks distinctly ovary-like or testis-like under a microscope. There are internal organs like the vagina, uterus, and fallopian tubes. There’s the menstrual cycle. There are external genitals. Breast development. Different patterns of body hair, and, often, of hair loss in middle age. Different patterns of growth, musculature, fat distribution, and bone structure, especially in the face and the pelvis. All of these physical changes are driven by different sex hormone levels during development, both before birth and throughout life; these are secreted not only by the ovaries or testes, but also by the adrenal glands, fat cells, and the pituitary gland in the brain.

Sex hormones also work on the brain, both during early development and later on, although given how poorly we understand how the brain works, quite a few unknowns about the timing, nature, and extent of this influence persist. These unknowns are hard to pin down, partially because, as highly social beings, the answer to that first question—“boy or girl?”—determines how a baby is raised, or “socialized,” which in turn profoundly influences that child’s self-concept or identity.

To further complicate things, out of all of these body, brain, mind, and societal variables, the only one that’s arguably binary is chromosomal makeup (and even there, chimerism and chromosomal variations can complicate the picture). Every other item in the list can be modeled as a continuous variable, with plenty of excluded middle. While genes usually kick off the cascade of events that ultimately drive all of the other effects, many factors may contribute to chromosomal sex not aligning with these other variables, all of which are a lot more socially, psychologically, and even anatomically relevant. Imagine these sex and gender variables like a bank of switches (or, more accurately, sliders) in a fuse box. Each influences the others, to different degrees and with time delays ranging from seconds to years. How many of us really have all of these sliders set unambiguously to one side or the other, and when there’s ambiguity, how can we talk about any single variable being the definitive one—the one that tells us who we “really” are?

Among the intersex population, and especially the most vexingly ambiguous cases, John Money found individuals with nearly every conceivable configuration of “fuse box settings.” 3 As a practicing psychologist who could team up with pediatricians, endocrinologists, and surgeons at Johns Hopkins, he was also far from an armchair observer. Money wanted to make his mark. He could move rapidly from bold hypotheses to grand theories to dogmatic convictions, and didn’t shy away from rolling up his sleeves. He put his ideas into practice, often with life-altering procedures on patients of all ages.

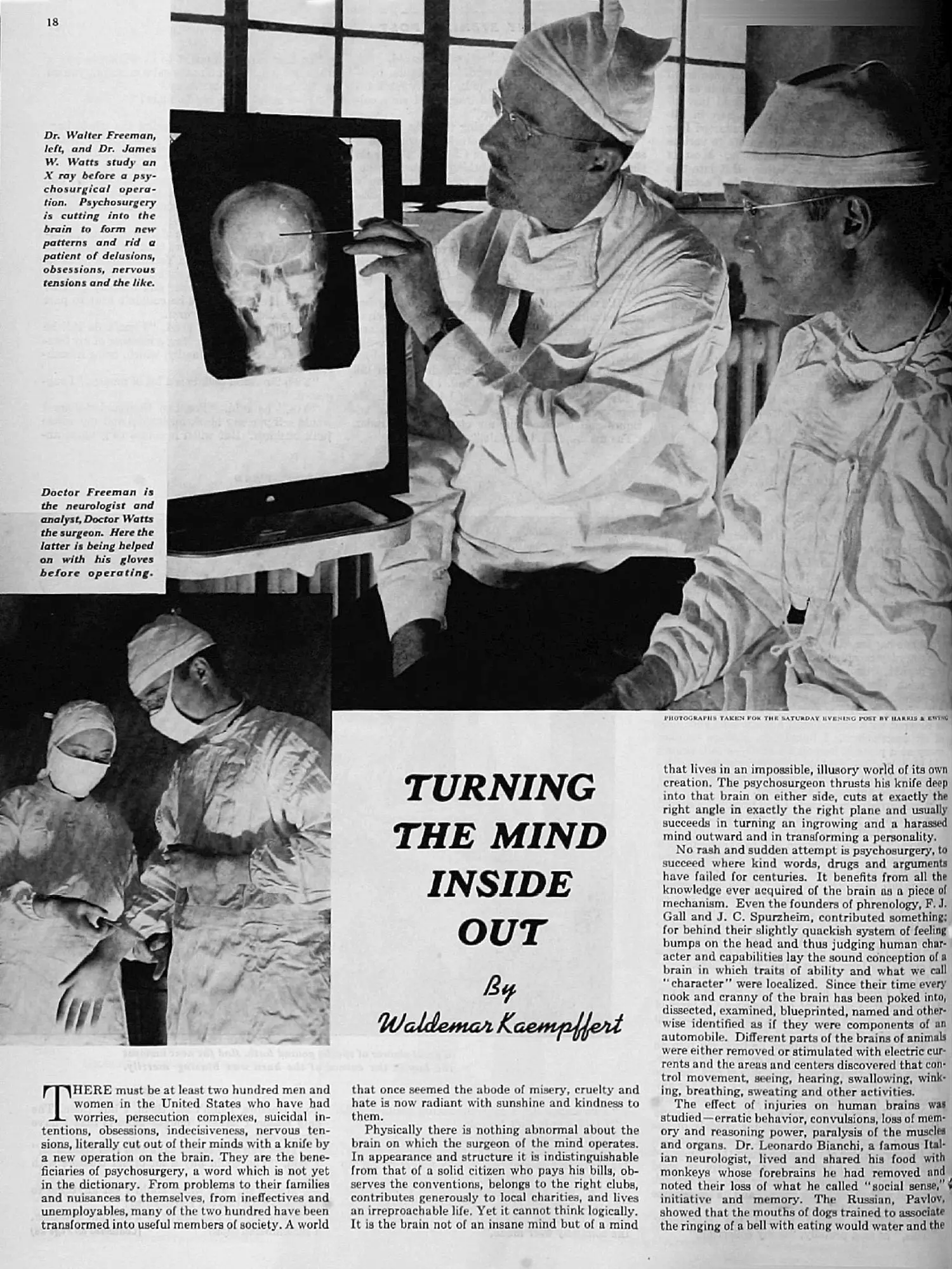

The whole mid-20th century medical establishment was drunk on its newfound power and overconfident in its burgeoning knowledge about the body. Doctors were less restrained by medical ethics than we are today, less humbled by complexity and unintended consequences, and less schooled in statistical rigor. 4

A case in point: in 1949, a couple of years after Money emigrated to America, the Nobel Prize in medicine was awarded to António Egas Moniz for his development of the prefrontal lobotomy. Evidence of its efficacy as a cure for mental illness was flimsy at best, though it was true that lobotomized patients tended to become more docile. Perhaps on that account, the procedure was performed enthusiastically throughout the United States over the following decade, not just on mental patients, but on depressed housewives, sullen teenagers, homosexual or supposedly “gender non-conforming” people (see Chapter 6), and unruly children as young as four years old. A six-year-old girl was lobotomized twice, and a twelve-year-old boy died from the procedure. 5

New Zealand, too, was swept up in the craze. In 1952, back once again in the Seacliff Lunatic Asylum near Dunedin, the troubled Janet Frame was scheduled for her lobotomy, having exhausted the other available therapies. Her mind was complex, restlessly analytical, and almost cripplingly self-reflective. She was embedded in a culture that presumed a clear dividing line between sanity and mental illness, with the various species of illness neatly taxonomized. Yet her detailed knowledge of these disorders, and her desire both to fit in and to stand out, created its own runaway feedback loops. Behavior, physiology, and identity were hard to untangle. It must have been tempting to cut the Gordian knot, even if the threads of that knot were her own neural pathways.

She had remained in contact with John Money, and wrote to ask his advice; to his credit, he advised against the procedure. Ultimately, though, the lobotomy was canceled at the last moment not due to his intercession, but because the hospital superintendent learned that she had just won one of New Zealand’s most prestigious literary prizes, the Hubert Church Memorial Award, for The Lagoon and Other Stories. 6 The book had finally been published that year by the Caxton Press in Christchurch. Janet Frame’s identity was finally established, once and for all: she was a writer.

Over the next five decades, she went on to write thirteen novels, two collections of poetry, and two more collections of short stories, winning many more awards and honors along the way. Even after her death in 2004, a stream of posthumous publications continued, including two short stories set in mental hospitals published in the New Yorker in 2008. 7

Since Money had first introduced her work to the Caxton Press’s founder, he deserves some credit for saving the frontal lobes, if not the life, of the writer many today consider New Zealand’s most preeminent—even if his understanding of her situation was muddled by preconceptions, and his professionalism questionable. The same failings would characterize his treatment of many other patients over the years.

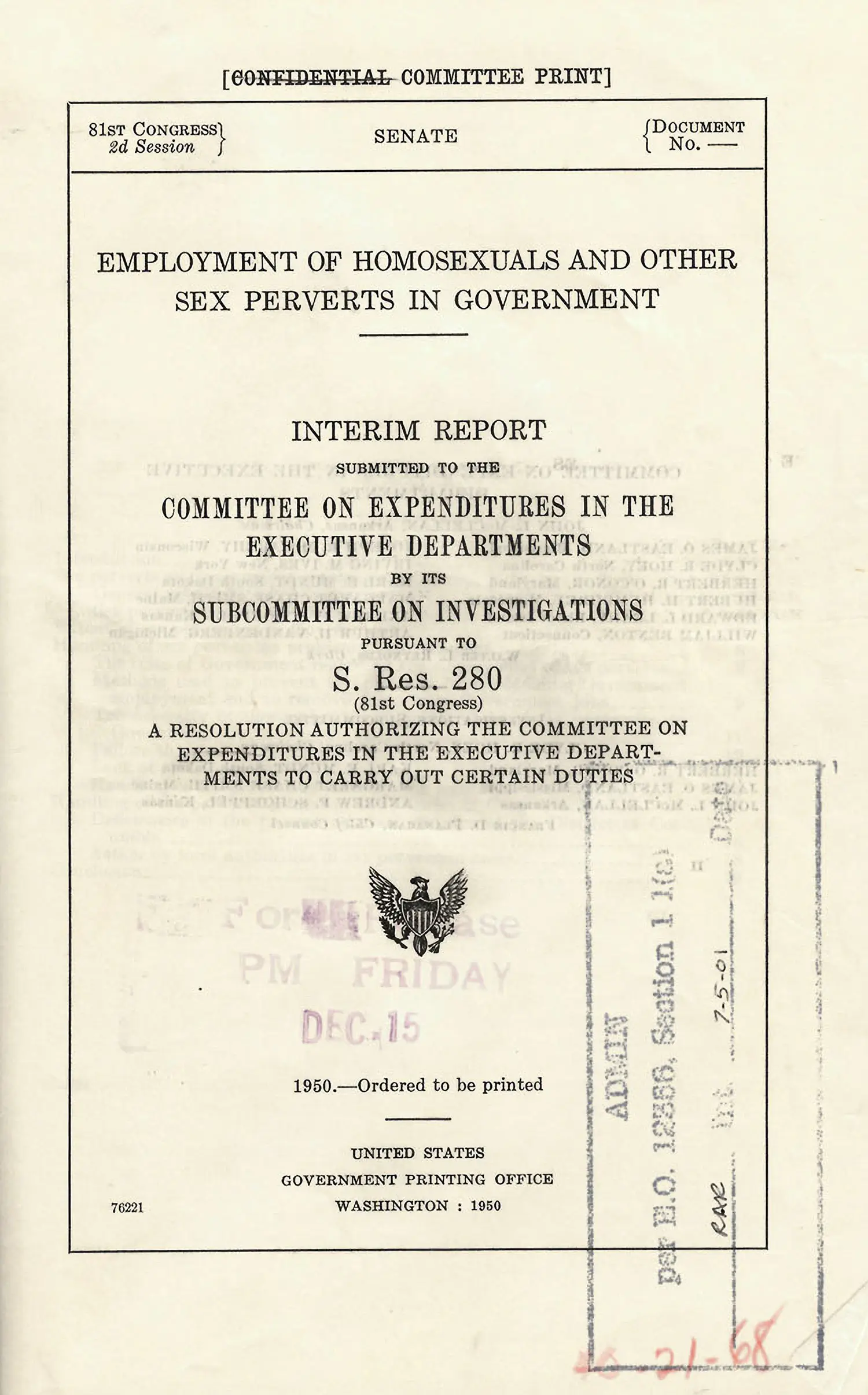

The fifties were deeply conservative, a period of social conformity and repression, of McCarthyism and J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI. While John Money’s views on sexuality were in many ways radical, they were also entirely consistent with the era in regarding the idea of a person growing up as anything other than a man or a woman anathema, a recipe for social shunning and mental disorder. Perhaps, in 1950s America, he wasn’t far off the mark.

As the years passed, social strictures began to loosen. The mounting backlash against sexual repression, the rise of hippies, and the Summer of Love did nothing to soften Money’s position on the binariness of gender, though. In a 1975 article, Sexual Signatures: On being a man or a woman, he and his coauthor Patricia Tucker wrote,

The irreducible requirement for the survival of humanity is that men and women cooperate as men and women at least well enough to survive, reproduce, and rear a new generation. A man’s ability to impregnate and a woman’s to menstruate, gestate, and lactate, are not, by themselves an adequate basis for cooperation […] Gender stereotypes, with all their many more or less arbitrary distinctions, provide the framework for that cooperation.

This was Money’s rendition of that hoary old classic, THE TRUE MISSION OF SEX. Given his belief in how essential the gender binary is, not only for the survival of the species but for the individual to fit into any kind of society, Money sought to solve the following problem: How could the medical establishment mobilize the array of emerging techniques in surgery, hormone therapy, and psychology to help a person with ambiguous “fuse box” settings become unambiguously a man or a woman, allowing them to take their place in society?

Surgery and hormones turned out to be more reliable tools than psychology. That is, it was a lot harder to convince someone who already thought of themselves in a gendered way to change their mind than it was to resculpt their body. For older patients, then, resculpting the body it was: and so the experts developed and refined the hormonal and surgical techniques known as sex assignment or sex reassignment—later known as gender confirmation. This was pioneering work for treating people we now call trans. Most of the original patients, however, were intersex.

Many regard Money’s greatest error his assertion that gender, as a psychological concept, could arise from a purely psychological origin. He assumed that while gender might be hard to overwrite later in life, it began as a blank slate, and could be freely molded in the first couple of years of life. In other words, if you looked like a girl and were told from infancy that you were a girl, then you would become a girl, and grow up into a woman; conversely for boys and men. It followed that the best care for intersex people would be to catch them as young as possible, ideally as newborns, decide whether their genitals would be easier to sculpt into a reasonably convincing vulva or penis, quietly do the surgery, and never look back. Money and coauthors spelled out these implications in their 1956 paper Imprinting and the Establishment of Gender Role:

[O]ur findings point to the extreme desirability of deciding, with as little diagnostic delay as possible, on the sex of assignment and rearing when a hermaphroditic baby is born. Thereafter, uncompromising adherence to the decision is desirable. The chromosomal sex should not be the ultimate criterion, nor should the gonadal sex. By contrast, a great deal of emphasis should be placed on the morphology of the external genitals and the ease with which these organs can be surgically reconstructed to be consistent with the assigned sex.

So it was all about the visible genitals, as it has been since time immemorial when we’ve answered “boy or girl?” in a snap visual judgment at birth. To be a girl, you just needed not to have anything oversized in your underwear, and to grow breasts after puberty. Being a boy was about being able to stand up to pee, and about not being ridiculed in the locker room. The rest—“gender stereotypes, with all their many more or less arbitrary distinctions”—would simply follow.

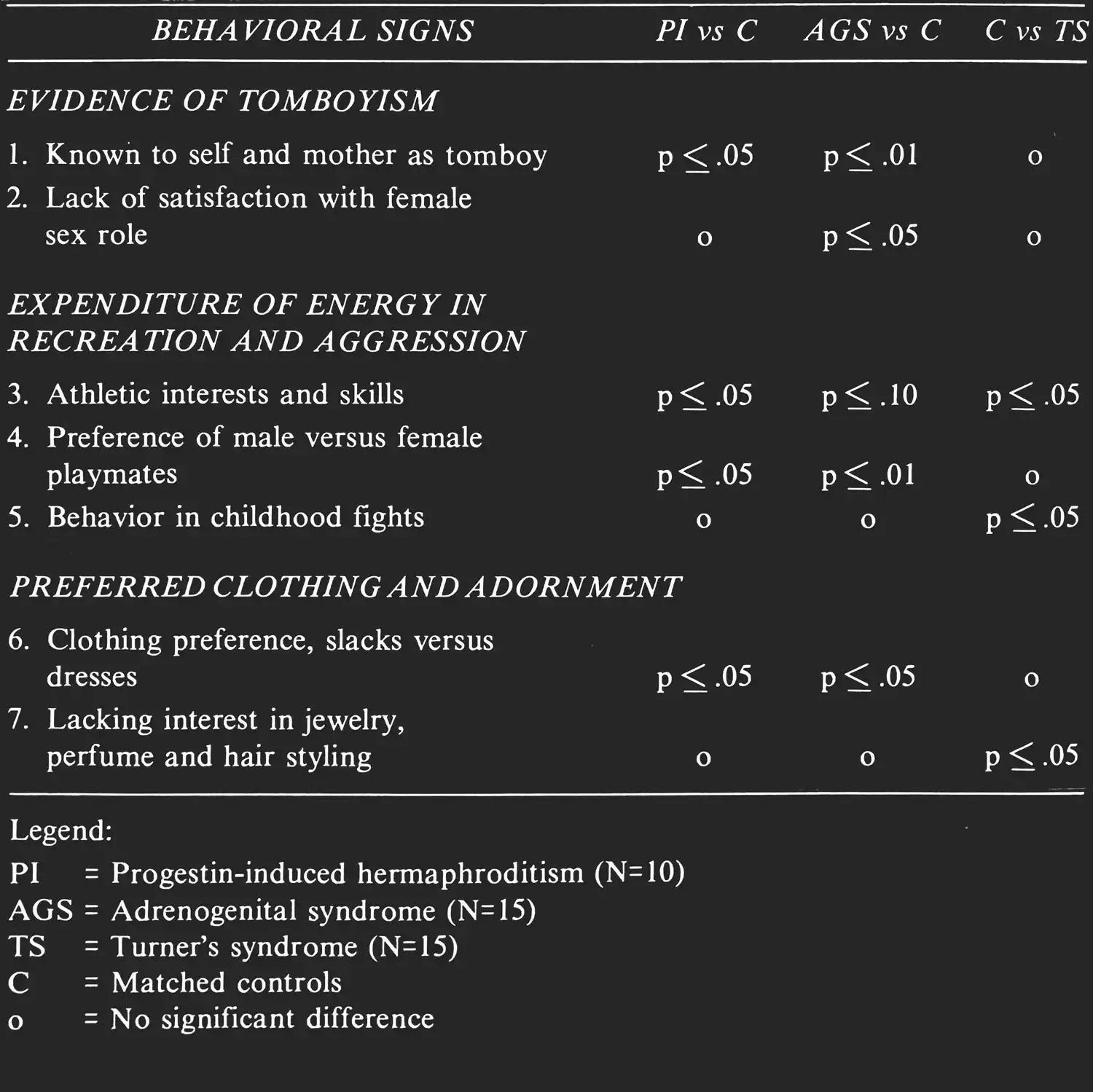

By the 1960s, critics of Money’s theory had noticed that his argument for the social flexibility of gender assignment was almost entirely based on accounts of successful gender assignments among intersex people. If the same hormonal processes that shape the body also shape the brain during early development, though, then a lack of strong sexual differentiation in the body might also imply that this population is, on average, unusually gender-flexible psychologically, especially at birth. In fact, those who begin near the center of the gender spectrum may not even need so much flexibility to “pass” as either women or men; just a nudge one way or the other, combined with society’s powerful bias toward perceiving gender as binary, might be enough.

So, Money needed stronger evidence that gender was socially constructed. In 1966, he got his chance. It came in the form of a desperate letter from Janet and Ron Reimer, the young parents of a pair of baby twins in Winnipeg.

Their story was harrowing. 8 When the twins, Bruce and Brian, were eight months old, they had developed phimosis, a constriction of the foreskin that made it painful to pee. A standard treatment at the time was circumcision. The babies were admitted to St. Boniface Hospital to undergo this minor procedure. Bruce was up first. Instead of a scalpel, an electrocautery machine was used—a device that uses electric current to simultaneously cut and cauterize tissue, instantly sealing the wound and preventing blood loss.

Something went horribly wrong. Whether due to incompetence, malfunction, or some combination, enough electric current was sent through baby Bruce’s penis to instantly cook it (“like steak being seared,” according to the attending anesthesiologist). The full extent of the damage was not immediately apparent, but the doctors, likely beginning to panic, left Bruce’s twin brother, Brian, untouched, and phoned the parents.

In Janet’s later account, by the time they were allowed to see Bruce, a couple of days later, his penis was “blackened, […] sort of like a little string. And it was right up to the base, up to his body.” Ron added that it looked “like a piece of charcoal. I knew it wasn’t going to come back to life after that.”

The doctors wrung their hands, unsure how to proceed. With virtually nothing left to work with, surgical reconstruction was deemed impossible. Dr. G. L. Adamson, head of Winnipeg Clinic’s Department of Neurology and Psychiatry, wrote of Bruce, “One can predict that he will be unable to live a normal sexual life from the time of adolescence: that he will be unable to consummate marriage or have normal heterosexual relations, in that he will have to recognize that he is incomplete, physically defective, and that he must live apart.”

Bruce’s injury was awful by any measure, but this pronouncement highlights the way it was even worse in 1966 than it would be today. Societal expectations of “normality” in all things sexual were so restrictive and judgmental that a boy or man lacking a penis would have been considered a monstrosity who “must live apart.”

Months later, deep in despair, Janet and Ron saw John Money on Canadian TV, expounding his theories on the social construction of gender and its implications for intersex babies. Grasping at a faint hope, the Reimers wrote him a letter. Bruce may not have been born intersex, but had the accident not left him in a similar state? He had no penis left to repair, but might surgical feminization be an easier route? Since he was still a baby, could he still be raised as a normal girl, if not a normal boy?

Money wrote back promptly: yes, yes, and yes. He encouraged them to bring their child to Johns Hopkins right away. As he would write later on, “Since planned experiments [with babies] are ethically unthinkable, one can only take advantage of unplanned opportunities, such as when a normal boy baby loses his penis in a circumcision accident.” 9

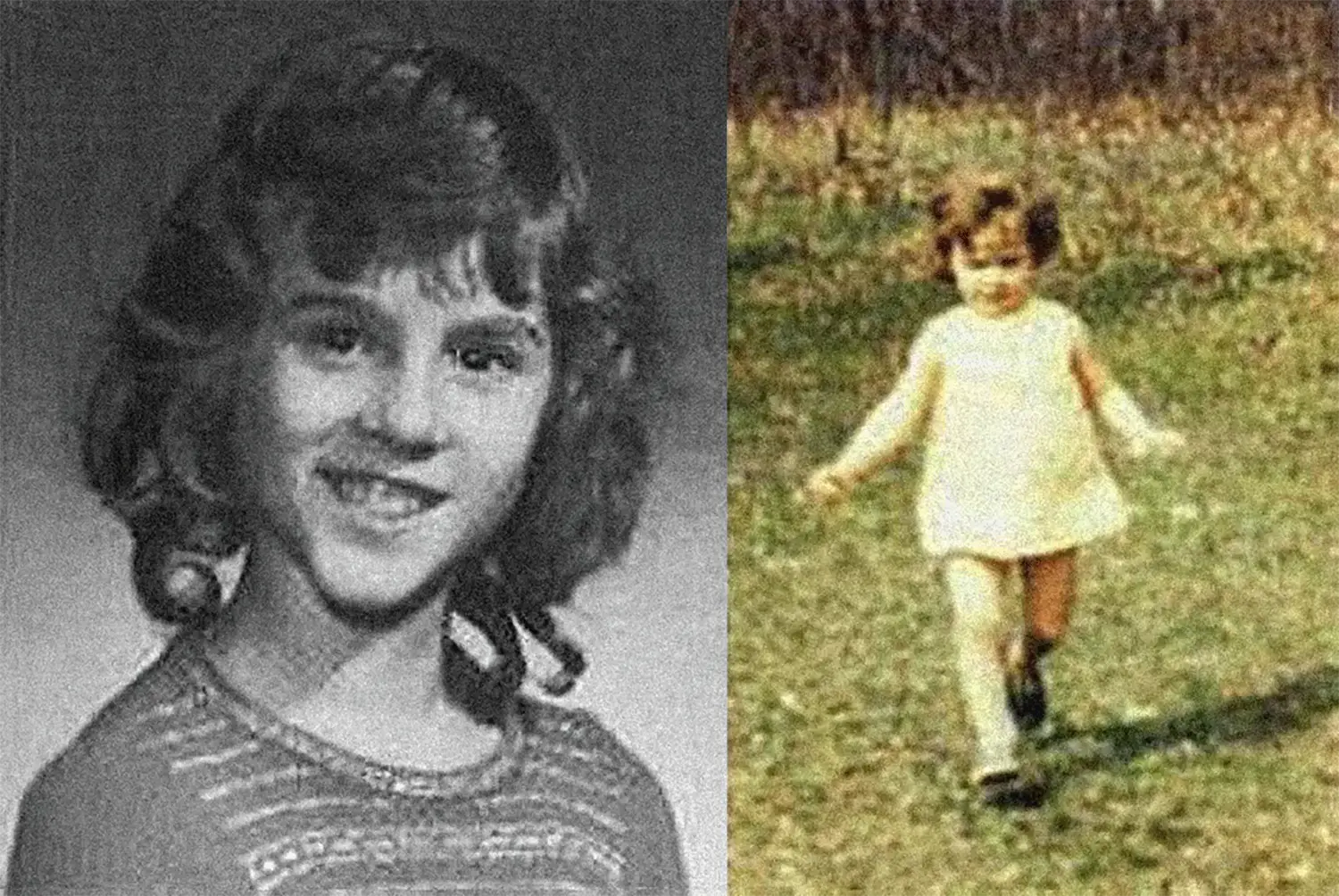

Full advantage was soon taken of this unplanned opportunity. Bruce’s testicles were removed, a rudimentary vulva was constructed, and he was given a new name: Brenda. Brenda and Brian (whose phimosis cleared up on its own, underscoring the tragic absurdity of the whole episode) were now a sort of mini, semi-controlled experiment, perfect for putting Money’s theory to the test: genetically identical and born male, but being raised as a girl and a boy.

The experiment would take years to unspool. Because Money was both highly invested in the outcome and highly charismatic—coercive, even—it’s not clear that the Reimers understood how speculative that theory really was.

There were some inherent tensions at the heart of Money’s reasoning. On one hand, he embraced the complexity of cybernetics and systems theory, with its model of the mind and body in terms of multidimensional, continuous, dynamically coupled variables. On the other hand, he also held fast to the binary schema of gender as conceived in the mid-20th century. These ideas were difficult to reconcile. Money assumed that socialization and peer pressure, if applied young enough, have unlimited capacity to steer a person’s gender identity in one direction or another; yet he also held that elaborate and arbitrary gender stereotypes are so fundamental to human nature that, in the Flintstones and Jetsons tradition, they transcend culture or era, even if the superficial details might vary. Further, we may begin life arbitrarily “plastic,” meaning flexible, able to be pushed toward the masculine or feminine by external social forces during early childhood. Yet somehow, despite the many variables involved, psychological health and “proper functioning” require that by a few years of age we find ourselves firmly on either the masculine or feminine end. The complexity of the system would—must—resolve into a single bit of information.

All of these assumptions are questionable, but taken at face value, they explain why intersex children were almost never told about their condition. As we’ve seen, they usually aren’t told, even today. That’s part of Money’s legacy.

As a young “girl,” Brenda Reimer was similarly in the dark. Janet and Ron knew exactly what had happened to their baby, and made as informed a decision as they could at the time—a decision that included maintaining secrecy. Arguably, they were better informed than most of the parents of intersex babies Money and his colleagues worked with. Although Money didn’t necessarily advocate keeping parents entirely out of the loop, he was adamant about controlling the message. If surgical and hormonal treatments could be described in some way that didn’t create any gender uncertainty on the parents’ part, it would both be more humane for them psychologically (given their presumed horror of the excluded middle) and would ensure their unwavering consistency in socializing their child according to the chosen gender:

Ninety-nine times out of a hundred, the public construes an hermaphrodite as being half boy, half girl. The parents of an hermaphrodite should be disabused of this idea immediately. They should be given, instead, the concept that their child is a boy or a girl, one or the other, whose sex organs did not get completely differentiated or finished. 10

Many accounts exist of paternalistic doctors following in Money’s footsteps over the years, and even, when they could, concealing a newborn’s intersexuality from the parents. The less they knew, the better. Especially before the internet and our modern passtime of WebMD doomscrolling, it would have been easy to hide behind technical jargon and the notion of unambiguously male or female genitals that were merely “unfinished” at birth, requiring minor cosmetic surgery to “correct.”

Money wrote triumphant accounts of Brenda Reimer’s case many times throughout the ’70s, withholding her name under medical anonymity. Everything was, reportedly, going swimmingly. Money’s yearly psychological evaluations of the twins at Johns Hopkins were relentlessly probing, boundary-violating, and ultimately abusive. They included simulated sexual intercourse he directed them to perform with each other as he watched, ostensibly to reinforce their opposite gender roles. Of course, the children were both traumatized.

Bizarre inconsistencies began to arise in Money’s accounts of Brenda’s development during this period, sometimes misrepresenting the child’s age by years or offering out of date photographic evidence of supposedly “feminine” body language and presentation. 11 At age 12, Brenda began (under protest) to take estrogen pills to induce female puberty, but it was increasingly clear to her that she was not really a girl, even as Money persisted in writing about the case as final proof that “the gender identity gate is open at birth for a normal child no less than for one born with unfinished sex organs.” 12 In 1978, Money wrote a final positive account of the Reimer case, though he admitted that Brenda was “tomboyish”; after that, he made no substantial comment on the matter for two decades.

During that time, psychology and sociology textbooks continued to cite Money’s research, and the Reimer case in particular, as powerful evidence of the socially constructed nature of gender. This fits into a broader humanist narrative about our being different from other animals due to our near-infinite adaptability and capacity to learn during our lifetimes. In the postwar years the idea of race, as a set of discrete biological categories with objective meaning, was being debunked by historical and genomic evidence; and if race was a cultural construct, 13 why not gender too? Some prominent feminist scholars eagerly embraced this position. A certain strain of the intelligentsia was, in other words, highly receptive to evidence in favor of “nurture” and against “nature,” especially in the politically contested realm of gender identity. It was a liberatory idea, promising social progress unconstrained by mere biology.

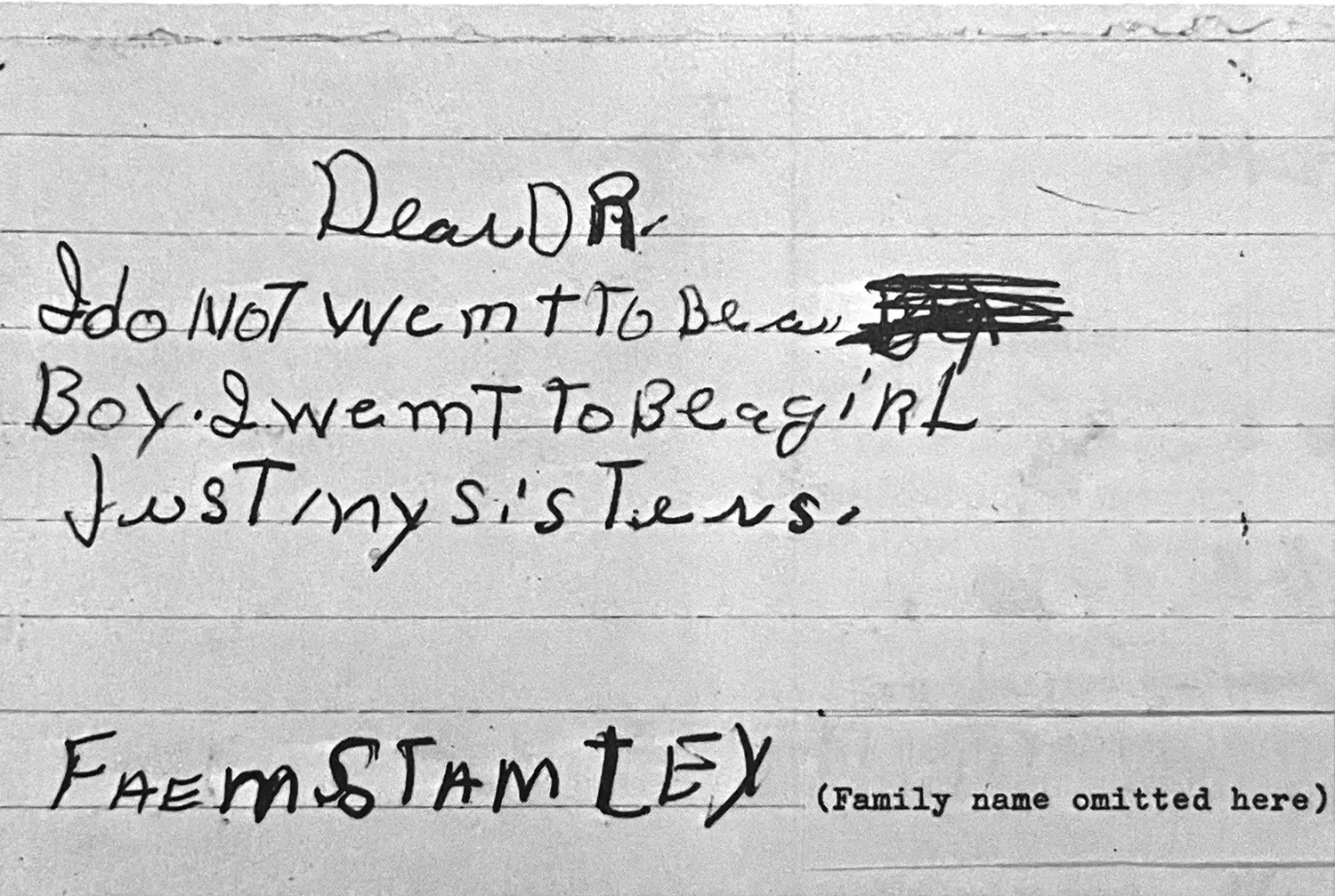

Meanwhile, shortly after medically induced puberty, the child at the center of this ethically fraught experiment dug in his heels and refused to continue to live as a girl—even prior to learning about his sex reassignment in infancy. When the truth finally came out, he changed his name to David, rejecting both “Brenda” and his original name, “Bruce.” In his mid-teens he elected a double mastectomy and phalloplasty (the surgical construction of a penis, a procedure he would undergo again with newly developed techniques a few years later). He began taking testosterone.

By age 25, David was married to a woman and had adopted her children. In 2000, he relinquished his anonymity and collaborated with journalist John Colapinto on a book telling the whole story, largely from the Reimers’ point of view. It made quite a stir.

Unfortunately, there was no “happily ever after.” In 2004, at age 38 and struggling financially, two days after his wife told him she wanted to separate, David Reimer committed suicide by gunshot to the head.

It would be an oversimplification to attribute David’s suicide solely to his mutilation and subsequent sex reassignment. In fact his twin brother, Brian, also struggled, and died from an overdose of alcohol combined with antidepressants two years earlier. Still, life would doubtless have gone very differently for the Reimers had the accident never occurred. David experienced intense emotional difficulties from childhood on, facing ceaseless bullying and lack of acceptance from peers, an inability to focus at school, and what we’d now recognize as gender dysphoria. On his last yearly visit to Johns Hopkins at age 13, he fled John Money’s office, saying he’d rather kill himself than ever go back. David’s relationships with those closest to him—his parents, his brother, and later his wife—were all damaged by the psychological consequences of what had been done to him. His story was deeply unhappy and, once public, struck a profound blow to the idea of gender as a purely social construct.

The publication of the Reimers’ story also marked a turning point in Money’s career. Although his work had always attracted criticism and troubling rumors circulated, he was still generally lionized in the 1990s, seen as a pioneering polymath, breaking taboos and conducting daring multidisciplinary research in the service of gender and sexual liberation. 14 But by the end of his life, in 2006, Johns Hopkins had been quietly distancing itself for years, pushing him into reluctant retirement. When the department he had founded at the hospital was shuttered, he left under protest, renting a dingy office off-campus and defiantly writing “Psychohormonal Research Unit” on a piece of paper taped to the wall.

Soon funding dried up entirely, and he retreated to his Baltimore apartment, increasingly isolated amid half a century’s worth of books, journals, art, erotic magazines, kitsch, and ephemera. Among the papers were the short stories and poems of his old patient, and later friend, Janet Frame. Though never fully at peace, she had escaped both the destructive feedback loops of her early years, and the straightjackets—literal and otherwise—of psychiatric institutions. She died of cancer the same year David Reimer had killed himself, but her artistic legacy was, if anything, still in ascent. She would win New Zealand’s top poetry prize three years after her death, for the posthumously published collection The Goose Bath. Money’s reputation, by contrast, lay in tatters. He had never imagined that he might become a footnote in her biography, rather than the other way round.

Once, there had been an unending stream of visitors; no longer. Dust settled on the fierce faces and proud wooden genitals of the Maori and West African sculptures looming from the walls. The tremor in Money’s hands turned out to be Parkinson’s disease, and as it advanced, dementia began to set in. He wrote about the experience, his graphomania turning inward. Meanwhile, the allegations mounted—not only of overweening arrogance and questionable clinical judgment, but of ethical monstrosities, scientific fraud, even pedophilia.

Some of his old friends still defended him, pointing out his pathbreaking intellectual achievements. Some of his former patients, too, remained devotedly grateful. In other quarters, though, he was being compared to Josef Mengele, the Nazi physician who had performed unspeakable medical experiments on prisoners in concentration camps. 15 When Money died, on the day before he would have turned 85, an intersex contributor to Daily Kos wrote, “I’ve often joked about the bottle of champagne I have had waiting for this event. […] It’s a good thing I’m not an obituary writer; I’d probably call him the butcher of Baltimore.” 16

It’s possible for both of these seemingly contradictory assessments to be valid. Ethical judgment, like sex, gender, and mental health, is often flattened into a binary—good versus evil—but real life resists such simplification. There are few perfect heroes—or perfect villains. John Money was neither.

Money, “Concepts of Determinism,” 1988.

Frame, An Angel at My Table: An Autobiography, 98, 1984.

Money, Biographies of Gender and Hermaphroditism in Paired Comparisons: Clinical Supplement to the Handbook of Sexology, 1991.

Statistical rigor in medicine has remained a problem. The “evidence-based medicine” movement dates only to the late 1980s, and even today, the evidentiary standards of many papers in medicine (as well as psychology and the social sciences) don’t pass muster. Only in recent years has widespread attention been paid to the ensuing replicability crisis in these fields. A reappraisal of standards for data quality and analysis has proven necessary even in “harder” fields, like neuroscience, biology, and physics. Button et al., “Power Failure: Why Small Sample Size Undermines the Reliability of Neuroscience,” 2013; Baker, “1,500 Scientists Lift the Lid on Reproducibility,” 2016; Junk and Lyons, “Reproducibility and Replication of Experimental Particle Physics Results,” 2020.

El-Hai, The Lobotomist: A Maverick Medical Genius and His Tragic Quest to Rid the World of Mental Illness, 175, 2005.

Goldie, The Man Who Invented Gender: Engaging the Ideas of John Money, 2014.

Frame, “A Night at the Opera,” 2008; Frame, “Gorse Is Not People,” 2008.

Colapinto, As Nature Made Him: The Boy Who Was Raised as a Girl, 2000.

Money and Ehrhardt, Man & Woman, Boy & Girl: The Differentiation and Dimorphism of Gender Identity from Conception to Maturity, 162, 1972.

Money, Venuses Penuses: Sexology, Sexosophy, and Exigency Theory, 140, 1986.

Downing, Morland, and Sullivan, Fuckology: Critical Essays on John Money’s Diagnostic Concepts, 2014.

Money and Tucker, Sexual Signatures: On Being a Man or a Woman, 98, 1975.

Cavalli-Sforza, Genes, Peoples, and Languages, 2000. Although racial categories are often arbitrary and absurd (e.g. the classification of people into “White,” “Indian,” “Coloured” and “Black” in South Africa under Apartheid), the notion that race is purely a social construct has once again been challenged in recent years by modern full-genome analysis; see Reich, Who We Are and How We Got Here, 2018.

For instance, in 1991, his friends and colleagues threw him a big party and published John Money: A Tribute, On the Occasion of His 70th Birthday. These essays and papers are glowing in their assessment of his contributions to sexology.

Downing, Morland, and Sullivan, “Pervert or Sexual Libertarian?: Meet John Money, ‘the Father of F***ology,’” 2015.

tvb, “The Death of a ‘Pioneer,’” 2006.