For billions of years, life has written itself into the very structure of our planet, making any sharp distinction between biology and geology murky at best. As the often brilliant, often cryptic cyberfeminist scholar Donna Haraway put it in 1995,

[…] the whole earth [is] a dynamic, self-regulating, homeostatic system; the earth, with all its interwoven layers and articulated parts, from the planet’s pulsating skin through its fulminating gaseous envelopes, [is] itself alive. 1

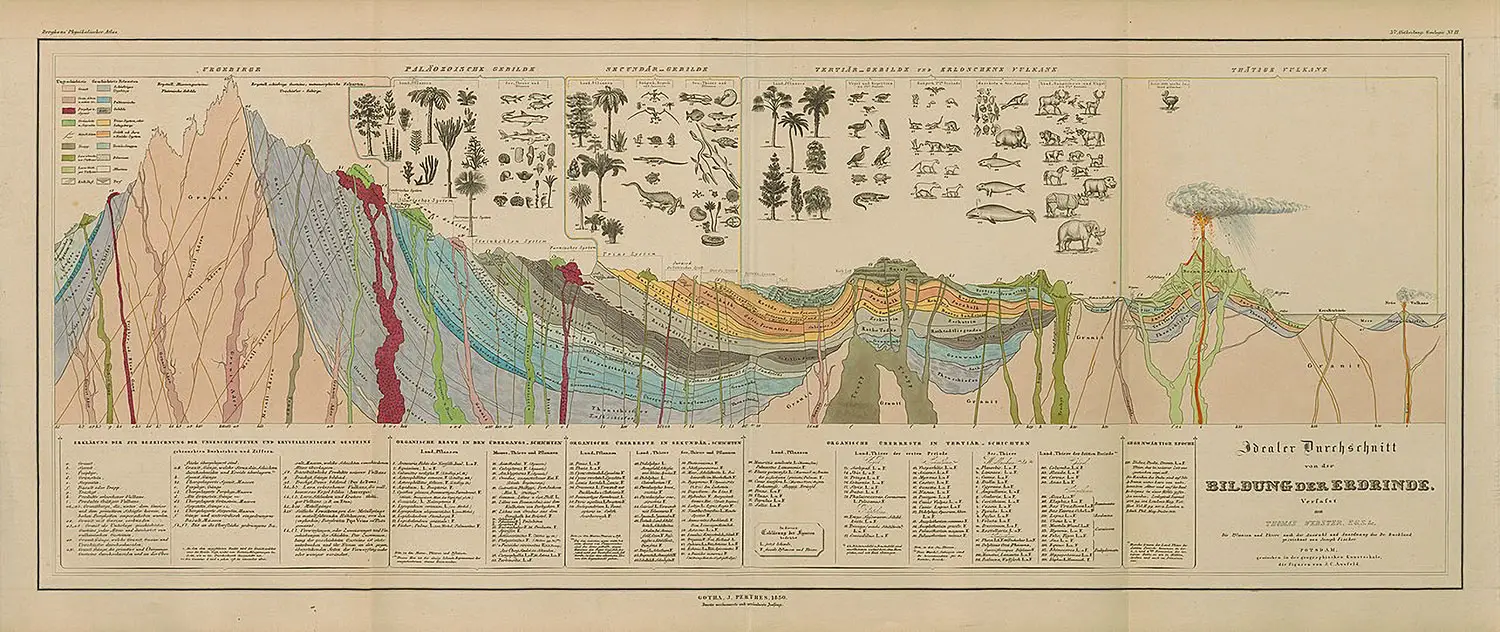

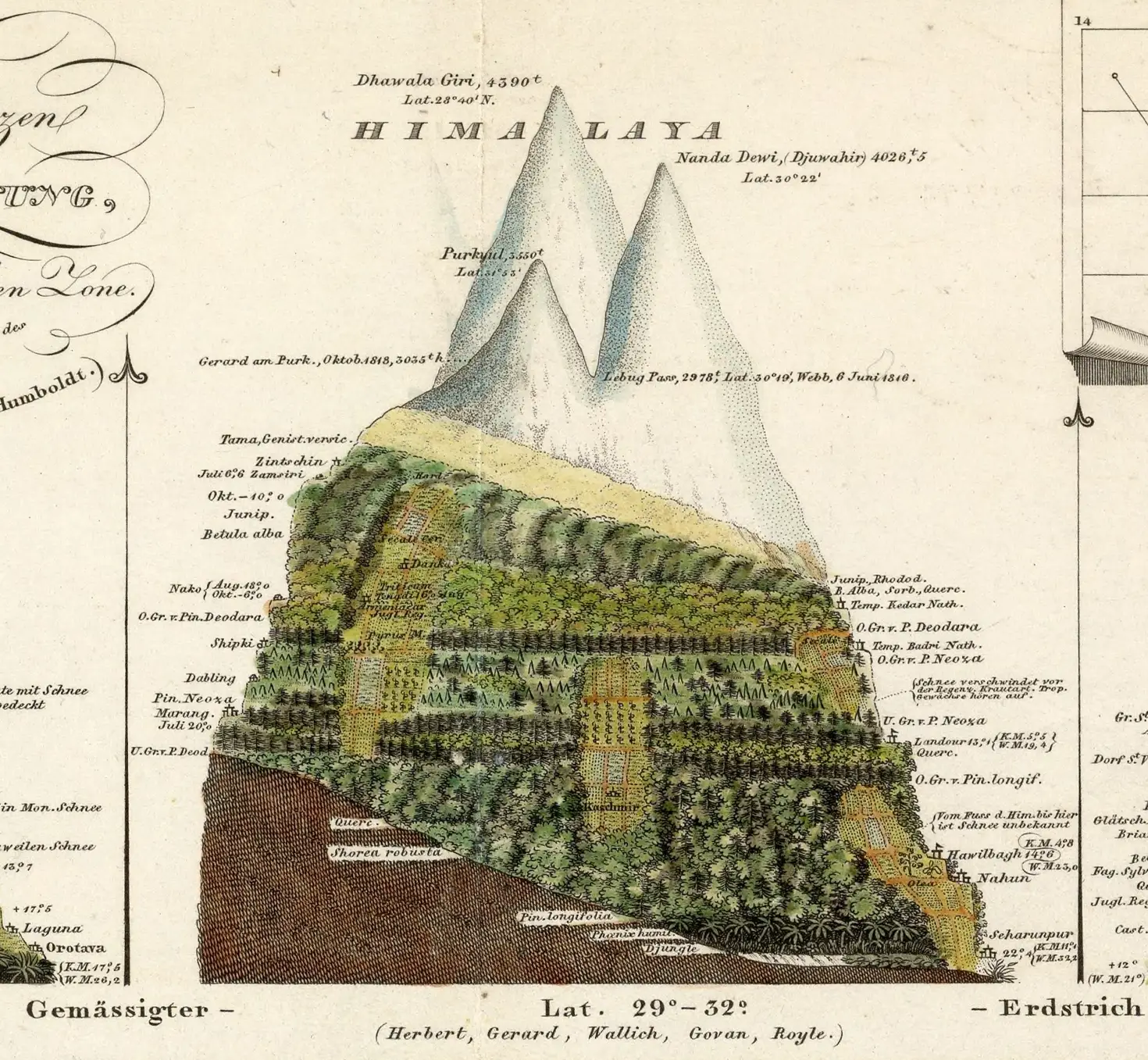

In the Western scientific tradition, geologist and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859) became an early advocate of this holistic view. It led him to sound alarms about ecological destruction and human-induced climate change as early as 1800.

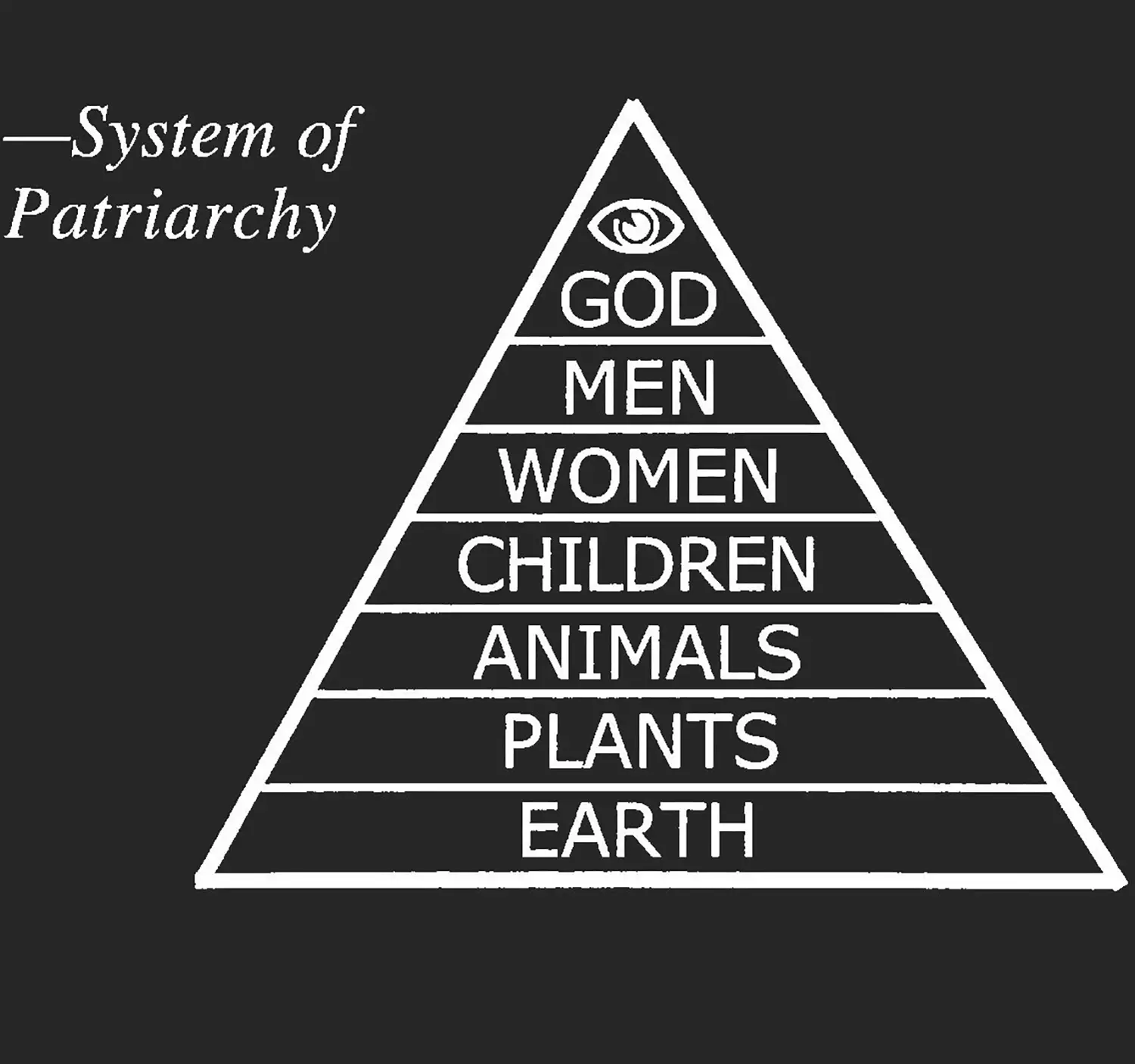

Humboldt’s observations, based on phenomena like the desiccation of the landscape following clearcutting in Venezuela’s Aragua Valley, were at once obvious and visionary. He was rowing against both prevailing scientific currents and millennia of religious dogma. Scientific progress had lately been advancing rapidly through controlled experiments, analysis, and classification, all of which worked by isolating and simplifying phenomena, studying them in the lab rather than observing them in context as parts of larger systems. Biblical doctrine, too, discouraged whole-system thinking, instead insisting on the static hierarchy of a Great Chain of Being that began with God above, then descended through the ranks of angels, people, animals, plants, and minerals. 2

According to Genesis, the Earth was only a few thousand years old (though contrary evidence was mounting), and God had separately created everything on it to serve a specific end: Man. Man was both distinct from Nature and rightly held dominion over her. The lower orders served the higher—like a military chain of command, or a corporate org chart. Hierarchies are certainly easier to reason about than the realities of mutually interdependent networks with no center, top, or bottom.

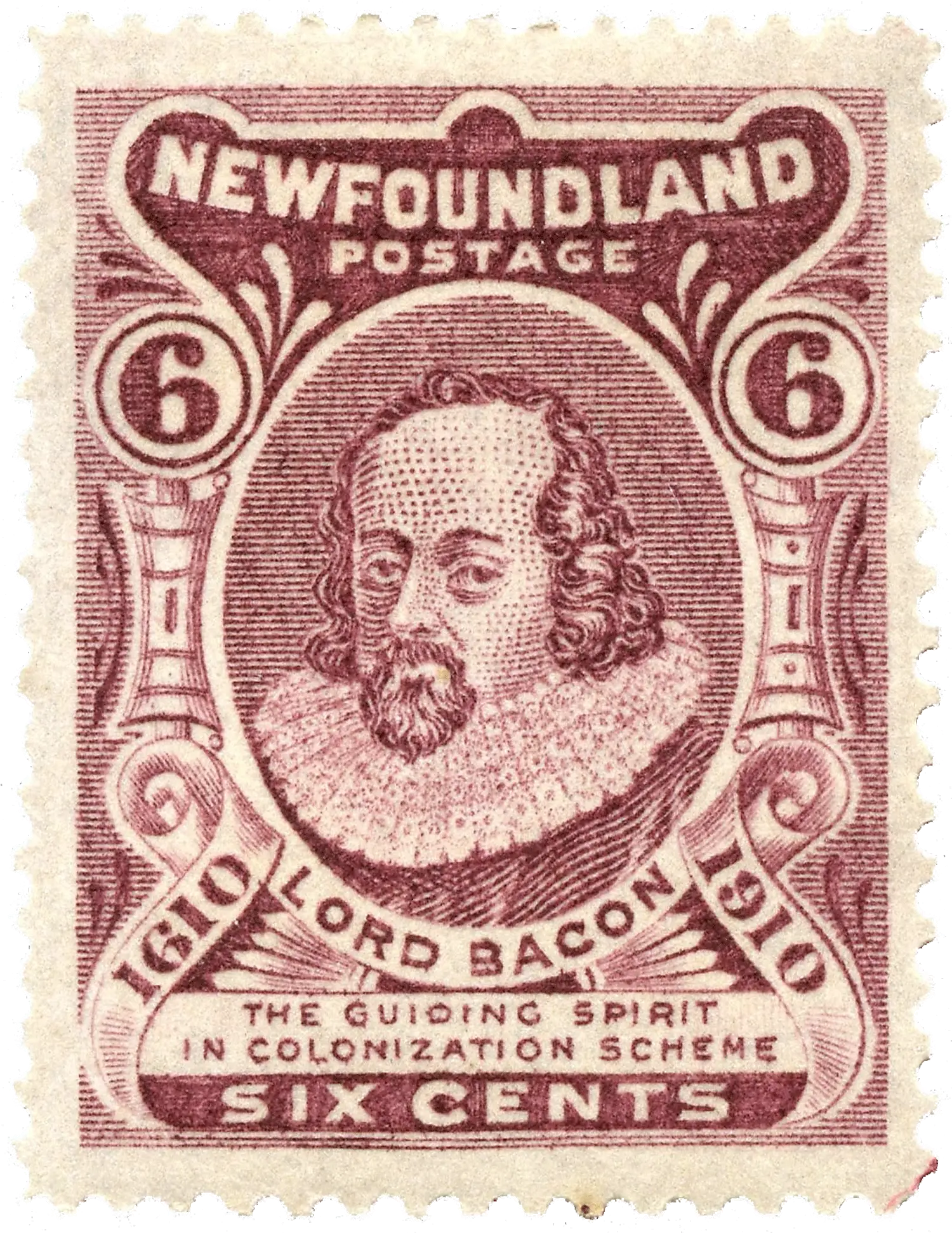

The traditional genders here—humanity (or “Man”) as male, Nature as female—aren’t accidental. In 1603, laying the foundations for the coming knowledge revolution, Francis Bacon had entwined religious and scientific doctrines in a Latin essay whose title can be translated as The Masculine Birth of Time, Or the Great Instauration of the Dominion of Man over the Universe. Writing from the vantage of a future scientist with godlike power exhorting his young apprentice, Bacon thundered,

I am come in very truth leading Nature to you, with all her children, to bind her to your service and to make her your slave […]; so may I succeed in my only earthly wish, namely to stretch the deplorably narrow limits of man’s dominion over the universe to their promised bounds […]. 3

This chilling passage frames science and technology as the rape of a femininized, subordinate Nature by Man, righteous in his lust for knowledge and power. Much is implied: that science and technology, as active arts, are the enterprises of men, not women; that Nature and the feminine are passive resources for male usufruct; that Man’s manifest destiny won’t be fulfilled until he has dominated literally everything in the observable universe.

Although the posthumously published Masculine Birth of Time is among the more obscure writings in Bacon’s storied career, it’s also a rare moment of candor, an unobstructed glimpse of the black hole whose gravitational well we’re still struggling to escape: patriarchy.

“Man dominating Nature” is not the only way to do science. Humboldt—obsessively measuring temperature and barometric pressure on every shore and mountain slope, talking to indigenous farmers, gathering samples and drawing connections—perceived the entanglement of living systems, the way nature resists simplification; how we must dance with it, not plunder it.

He came to understand the suicidal consequences of ecological colonialism and unfettered resource extraction through lengthy travel in the New World, far from home. It’s unlikely that he would have developed these insights had he stayed in Germany, among the long-cultivated fields of Saxony or in the coffeehouses of Jena. Understanding required distance and perspective—and time.

.webp)

Many years later, astronaut William Anders also attained such a planetary perspective. On Christmas Eve of 1968, in orbit around the moon, he exclaimed, “Oh my God! Look at that picture over there! There’s the Earth coming up. Wow, that’s pretty.” The photo he took with his boxy modified Hasselblad, now known as Earthrise, galvanized the environmental movement. As the world shrank, Humboldt’s vision had become more accessible.

Dawning popular awareness of the finite nature of our world, its fragility, and the interconnectedness of all its systems inspired researchers James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis to develop the Gaia Hypothesis, first articulated by Lovelock in a famous 1972 paper, Gaia as Seen Through the Atmosphere:

[T]he sum total of species is more than just a catalogue, “The Biosphere,” and like other associations in biology is an entity with properties greater than the simple sum of its parts. Such a large creature, even if hypothetical, with the powerful capacity to homeostat [regulate] the planetary environment needs a name; I am indebted to Mr. William Golding for suggesting the use of the Greek personification of mother Earth, “Gaia.” 4

Though initially Lovelock made his case hesitantly, couching it in qualifiers like “hypothetical,” his was a stronger statement than Humboldt’s. Beyond pointing out interrelations between lifeforms and the mutual shaping of biology, atmosphere, and geology, he was proposing that we view Earth as a single great organism, that we call her Gaia, and that we consider ourselves part of that organism.

Margulis, whose groundbreaking findings as a cellular biologist established symbiosis (or mutual interdependence) as fundamental to all life on Earth, was nonetheless deeply skeptical of the name Lovelock had chosen:

The Gaia hypothesis is a biological idea, but it’s not human-centered. Those who want Gaia to be an Earth goddess for a cuddly, furry human environment find no solace in it. […] Gaia is a tough bitch—a system that has worked for over three billion years without people. This planet’s surface and its atmosphere and environment will continue to evolve long after people and prejudice are gone. 5

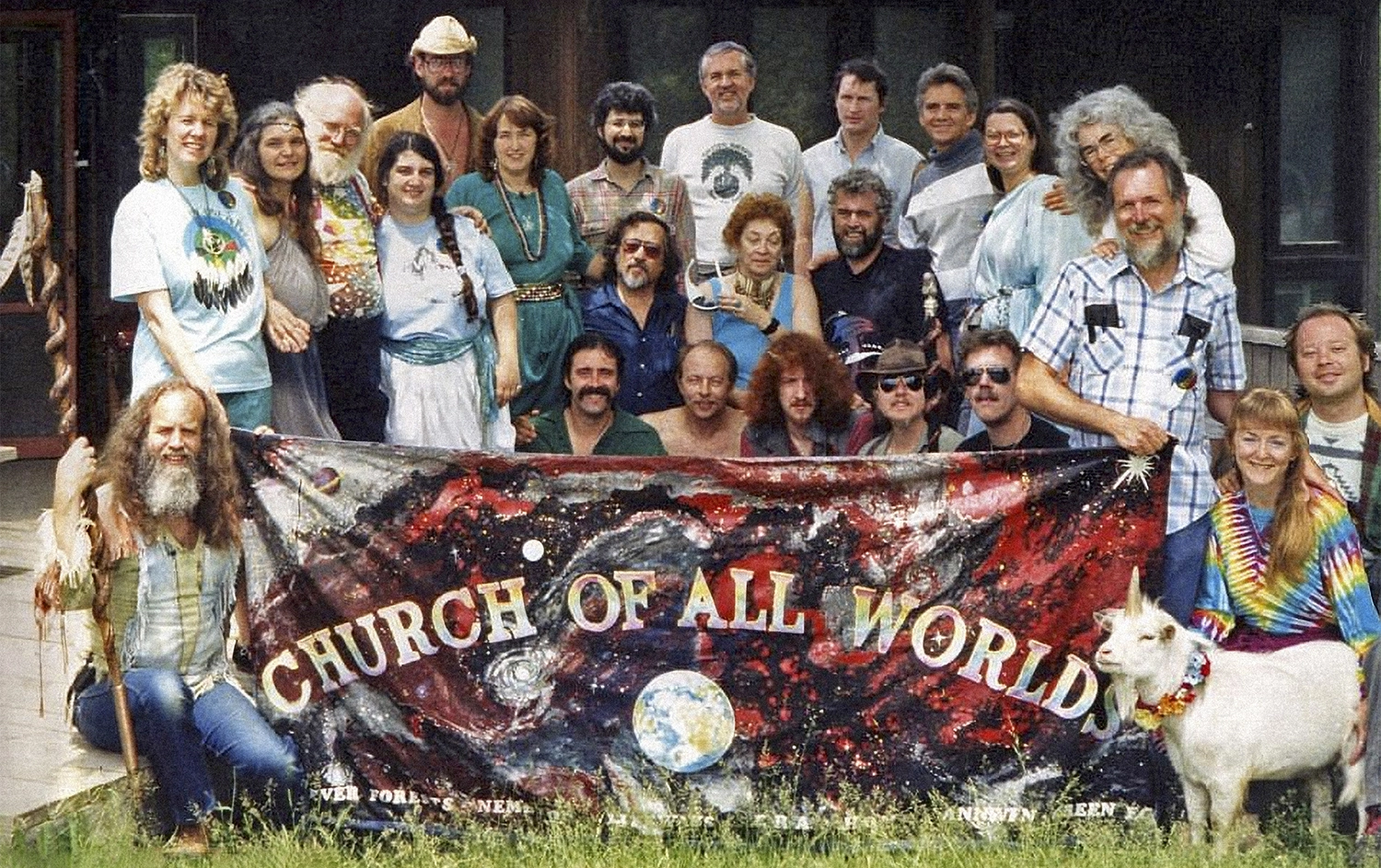

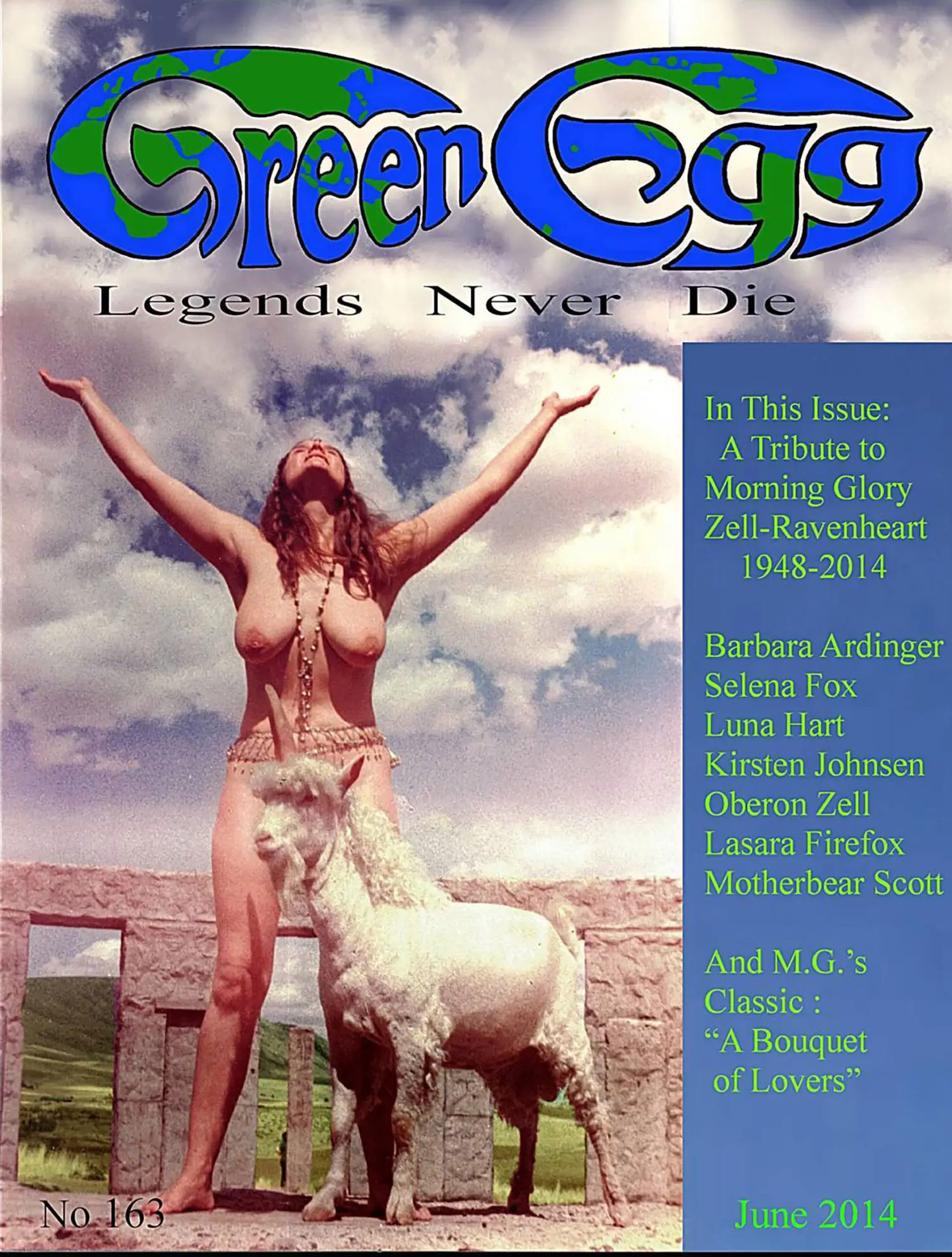

It turned out that Gaia had already been given an incongruously cuddly name the year before—Terrabia—by Timothy Zell, founder and Primate of the Neopagan Church of All Worlds. Though Lovelock and Margulis were almost certainly unaware of it, they had been scooped by Zell’s 1971 article, TheaGenesis: The Birth of the Goddess, in the Church’s (decidedly non-peer-reviewed) journal Green Egg. Influenced by science, but also borrowing liberally from Eastern and indigenous belief systems where planetary-scale animism goes back thousands of years, Zell had written:

We now know that our planet, Mother Earth, is inhabited not by myriad separate and distinct organisms, each going its own way independent of all the others, but rather that the aggregate total of all the [living] beings of Earth comprises the vast body of a single organism—the planetary Biosphere itself. Literally, we are all One. Further, we now realize that the being we have intuitively referred to as Mother Earth, The Goddess, Mother Nature, The Lady, is not merely a mythical projection of our own limited visions, but an actual living entity, Terrabia, the very biosphere of Earth, in whose body we are mere cells. Forced by this discovery to re-examine our religious language and conceptualizations, we have arrived at the following definition of Divinity (which, incidentally, includes within it the essential nature of the Divine as expressed by all other religions): “Divinity is the highest level of aware consciousness accessible to each living being, manifesting itself in the self-actualization of that being.” Thus the living Biosphere is Goddess in Her evolving self-actualization. As in the corporate body of the great planetary organism we are all One, so are we all God! (More correctly, we are all Goddess, since Mother Earth is of feminine gender.) This concept has been recognized, though not heretofore fully understood, in the basic aphorism of Neo-Pagan religion; the phrase “Thou art God.” 6

So, the hippies beat the scientists to the punch—at least, in the modern West. 7

The hippies and scientists both committed a seemingly obvious category error, though, by persisting in thinking of the Earth as female. After all, sexual differentiation is just a reproductive trick particular to certain branches of Earth-life—including Homo sapiens, most other animals, and many plants, but these account for just a fraction of Earth’s biomass.

_(33389628036).webp)

Our planet also hosts vast numbers of cells and larger constituent organisms that are unsexed, hermaphroditic, or based on reproductive schemes so profoundly queer (in multiple senses of the word) that our provincial notions of sex and gender are upended. 8 According to biologist Merlin Sheldrake, 9 the split gill fungus, Schizophyllum commune, “has more than twenty-three thousand mating types, each of which is sexually compatible with nearly every one of the others”! Even among our closer animal relatives, surprises abound. Some fish, for instance, change sex as they age, and the white-throated sparrow appears to have four sexes with distinct genotypes and mating behaviors. 10

So, it makes little sense to talk about Earth as a whole in gendered (not to mention binary) terms. Perhaps we can call it progress, though, for a syncretic Neopagan mythology about an all-encompassing Earth-mother to supplant an Iron Age mythology starring a domineering and vindictive patriarch-God.

Gaia isn’t an easy concept. For one thing, it’s squicky to think about lifeforms living inside other lifeforms. The chest-bursting xenomorph of the Alien movie franchise may come to mind, and the real-world endoparasitic horrors that inspired it—tiny wasps laying their eggs inside the bodies of bigger wasp species, or Cordyceps fungi controlling the minds of ants. Ugh, boundaries!

In reality, though, life is never isolated from other life; living worlds within worlds nest like matryoshka dolls. It has become a trope to point out that you have ten times as many bacteria living in your gut as you have cells of “your own” in your entire body.

The rabbit hole goes far deeper. Within every one of your 30–40 trillion cells, there are anywhere from dozens to hundreds of thousands of tiny sausage-ish mitochondria, which may dynamically split, fuse, and form intricate layered structures. 11 Mitochondria in turn contain the folded-up membranes or cristae whose electric charge, maintained by trans-membrane ion pumps, powers all animal life. Unfolded, the cristae in your body would cover five football fields, and store the power of a lightning bolt. 12 As yet, human-engineered power generation and battery technologies can’t even approach this biological marvel.

Lynn Margulis was the first to realize that mitochondria (as well as chloroplasts, their photosynthetic counterparts in plant cells) were once free-swimming bacteria. In fact they’re still bacteria, with their own DNA and their own reproductive cycle, albeit by now mutually dependent on their host cells—much the way we both depend on and have reshaped our host planet.

Margulis’s epiphany was mind-blowing—maybe too mind-blowing. In response to one grant application, a reviewer wrote, “Your research is crap. Don’t ever bother to apply again.” 13 Her now-classic 1967 paper, On the Origin of Mitosing Cells, was rejected by fifteen journals before finally being accepted, maybe on a slow day, by The Journal of Theoretical Biology. 14

In a 1991 book, Two Plus Two Equals One: Individuals Emerge from Bacterial Communities, Margulis and a coauthor wrote a sentence that sums up much of this book:

Identity is not an object; it is a process with addresses for all the different directions and dimensions in which it moves, and so it cannot so easily be fixed with a single number. 15

In 1999, toward the end of her stormy career, she was finally awarded the National Medal of Science. She died in 2011, aged 73.

While revising this chapter in the summer of 2022, I learned that her old collaborator, James Lovelock, had also died, at 103 years of age. He wrote his last book, Novacene, at 100. Though the Gaia hypothesis was also long mired in controversy, the scientific establishment was quicker to recognize Lovelock’s contributions than those of Margulis. Lovelock was made a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1974, and later, a Companion of Honor and a member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire: thus, a knight.

Not to be outdone, the man once known as Timothy Zell, now 80 years old and styling himself Oberon Zell-Ravenheart, is no mere honorific knight, but “a true Wizard in the traditional sense,” according to his website. 16 He’s also the Headmaster of the Grey School of Wizardry, open to “all seekers, young and old,” and offering “more than 500 classes in 16 Departments,” from “Alchemy, Healing, and Divination to Ceremonial Magick and Defense against the Dark Arts.” 17

Let’s rewind.

Throughout the ’70s, Zell continued to write and speak in public about his TheaGenesis epiphany. With a nod to Lovelock and Margulis, he had replaced Terrabia with Gaia by the time he delivered the keynote address at the 1973 Gnosticon Aquarian festival. Pagans, witches, druids, shamans, astrologers, and seekers of every other stripe had converged on the unlikely city of St. Paul, Minnesota for this happening.

Morning Glory, a young witch in the audience, was smitten. Although already in an open marriage, she immediately resolved to leave her husband and join her life to the charismatic Zell’s. They were married the following year in a handfasting ceremony at the Spring Witchmeet, presided over by High Priestess Carolyn Clark and the Archdruid Isaac Bonewits, the latter a skinny Pagan activist who had recently graduated from UC Berkeley with a degree in Magic (sadly, the last they would ever grant).

Soon afterward, Morning Glory became the Assistant Editor of Green Egg, hosting collating parties in St. Louis at which an often naked crew of volunteers met to staple together and mail out the quarterly journal. Following a period of study lasting the customary year and a day, Morning Glory was ordained High Priestess of the Church of All Worlds. Their Midwestern idyll proved fleeting, though; the Zells felt the call of the West.

In 1975, they outfitted a schoolbus, christened the Scarlet Succubus, for a one-way road trip to California. They eventually settled on a ranch in Mendocino County, opening a magic shop in a nearby town and developing a technique for creating “unicorns” by performing horn surgery on baby goats. These were kept as pets, exhibited at Renaissance Faires, and licensed for a time to the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus.

Surprise: the Zell-Ravenhearts were never a conventional Nuclear Family. They lived communally with a slowly evolving cast of additional partners and occasional children, all of whom were involved in the commune’s upkeep and collective enterprises.

This mingling of communal, religious, sexual, reproductive, and commercial concerns in an intentional lifestyle has a rich, if fringe, history in the United States. 18 The term “free love,” for instance, was coined by John Humphrey Noyes, founder of the Oneida Perfectionist community in upstate New York in 1848. 19 The Perfectionists practiced group marriage and rigorous birth control, lived in the collectively owned Mansion House, and earned income from a variety of cottage industries, including Oneida silverware, which is still in production today.

The Nicholses, whom we have already encountered, also advocated free love, in addition to universal suffrage, opposition to capital punishment, full access to education for women, vegetarianism, and many other then-radical ideas. In a lightly fictionalized autobiography written in 1855, Mary Gove Nichols railed against the strictures of her day:

I must move among all men as sepultured alive, because a man owned me by law. […] [T]he fact that we received a gentleman as a boarder in our family was an evidence of evil in me, to ultra-moralists, that was irrefragable. I could conform to no such code of morals. […] I had always been a lover, but […] I had thought that all love was sinful that was not according to law, that had not the stamp of property, the “ear-mark” of ownership upon it. If a man were pleasant to me, it had been a reason for shunning him. If the touch of his hand or the sound of his voice sent a thrill through [my] heart, it was a sufficient reason why I should not touch the one nor listen to the other. I lived for a long time under a solemn vow to allow no pleasant friend of the opposite sex to hold my hand. And in this horrible asceticism, this suffocation of my life’s life, I had lived, […] and had thrown all my energies into efforts for the good of others. 20

As well as being an unusually reliable source of information in print about birth control, Thomas Low Nichols’s 1853 book Esoteric Anthropology also found much to critique in the patriarchal and monogamous norms of the time—though, as with many utopian thinkers, his idealism tended to deny inconvenient social and psychological realities. In describing sexual jealousy, he wrote:

I believe it to be a morbid, mean, bad feeling, caused by poverty, lack of self-esteem, distrust, suspicion, and a craving for more than we fear we have an honest right to. It is a feeling every one is ashamed of and disclaims, which is proof enough of its badness. It is everywhere a subject of ridicule, because men are conscious that it is a shabby feeling. It grows, in most cases, out of the idea of property in each other. As long as a man thinks he owns a woman, he will guard her like any other piece of property, and consider any intercourse with her a trespass, only so far as he permits: and the same of women. […]

I have seen women who assured me that they had no power to love but one man at a time, though capable of a succession of amours. Others believe that one love is enough for a lifetime. There are others who seem to love two, three, or even more, with various degrees of passion, but all amatively. I knew one woman who slept with two men on alternate nights, and she declared that she loved them both, and could not endure the thought of parting with either. They were two respectable business men in New York, satisfied with her, and not jealous of each other. She had a child, and each believed it his, and loved it accordingly. But, then, a man generally loves the child of a woman he loves, whether he believes it his or not. I think men are, at least, equal to women in this respect. […] I believe liberty to be the truest bond, and best security for love. 21

These were remarkably modern ideas, of which the Zell-Ravenhearts would doubtless have approved.

Green Egg underwent a long hiatus after the move to California. Eventually, aided by the newfangled personal computer and desktop publishing software, it was revived under the editorship of Diane Darling, a member of the Ravenheart commune from 1984 to 1994. The topics covered ranged from the cosmic to the personal, as described by Darling in a retrospective anthology:

Why did we [publish Green Egg]? What were we thinking? I thought we were saving the world by reviving human consciousness of the sacred living Earth and of our true ancestral roots. […] By displaying and discussing our own, then-radical lifestyle experiments, we hoped to turn the wheel of social evolution for the benefit of our Mother. […] We were surfing the bleeding edge of cultural shift […]. 22

This conflation of cosmology with lifestyle is characteristic of many intentional communities. It can whiff of grandiosity, doubtless contributing to the marginalization of such movements… even if, at the core, their practices and beliefs are no stranger than anyone else’s.

Intentional communities have arisen in every era, but their numbers seem to have exploded in recent Western history. Perhaps this owes to WEIRD propensities for individualism, disregard for the authority of elders, and a taste for “rational” behavior, meaning a through-line whereby external actions are anchored by internally consistent beliefs about the way the world works, as opposed to received wisdom. 23

Thus, in questioning and reimagining the principles that govern the universe, intentional communities also reimagine the social norms governing daily life—and vice versa. To the WEIRD way of thinking, the cosmic is personal. And, perhaps especially to the American way of thinking, good ideas are “ideas worth spreading.” 24 The United States has always leaned evangelical—whether the ideas are temperance or free love, spiritualism or the gospel of prosperity, Mormonism or TED talks.

At Diane’s suggestion, Morning Glory contributed an article to Green Egg in 1990 about the norms underpinning her commune’s lifestyle, and lessons learned. As she put it,

Having been involved all my adult life in one or the other Open Marriages (the current Primary being 16 years long), I have seen a lot of ideas come and go and experimented with plans and rules to make these relationships work for everyone involved. […] [T]here are some sure-fire elements that must be present for the system to function at all and there are other elements that are strongly recommended on the basis that they have a very good track record. 25

This essay, A Bouquet of Lovers, became an instant (albeit cult) classic. In it, Morning Glory coined an odd, half-Greek, half-Latin word to describe consensual non-monogamous relationships: polyamorous. 26

She prophesied thusly:

I feel that this whole polyamorous lifestyle is the avant garde of the 21st Century. Expanded families will become a pattern with wider acceptance as the monogamous nuclear family system breaks apart […]. In many ways, polyamorous extended relationships mimic the old multigenerational families before the Industrial Revolution, but they are better because the ties are voluntary and are, by necessity, rooted in honesty, fairness, friendship and mutual interests. Eros is, after all, the primary force that binds the universe together; so we must be creative in the ways we use that force to evolve new and appropriate ways to solve our problems and to make each other and ourselves happy.

Haraway, “Cyborgs and Symbionts: Living Together in the New World Order,” xiii, 1995.

Lovejoy, The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea, 1964.

Bacon, Temporis Partus Masculus, 1603; translation in Anthony Wilden, 1972; see also Farrington, 1951.

Lovelock, “Gaia as Seen Through the Atmosphere,” 1972.

Margulis, “Gaia Is a Tough Bitch,” 140, 1995.

Zell, “TheaGenesis: The Birth of the Goddess,” 1970.

Contested wizardly spelling alert. In November 2022, Zell wrote (personal communication): “[I]n all my own references (except the statue, for marketing reasons) I [use] the traditional and universal (prior to Lovelock) Latin spelling of ‘Gaea’ (Greek Gē)—from which we derive all our Earth-terms (geography, geology, geometry, geocentric, geode, etc.). The ‘Gaia’ spelling with an ‘i’ was a misunderstanding on Lovelock’s part of the word he heard from his friend William Golding, and he just spelled it phonetically, having, as he himself said, ‘no Classics.’ Indeed, he first thought Golding had said ‘gyre.’ But the diphthong ‘ae’ can be pronounced either ‘eh’ or ‘eye’ (I have all this in Lovelock’s own words, quoted in my recent book: GaeaGenesis: Conception and Birth of the Living Earth—which should be listed in the bibliography of this book).” With thanks, it has been duly listed. However, Lovelock’s misspelling has stuck, and is now more common by far, so in keeping with this book’s theme of embracing cultural evolution, I, too, have stuck with “Gaia.”

Kaishian and Djoulakian, “The Science Underground: Mycology as a Queer Discipline,” 2020.

Sheldrake, Entangled Life, 2020. See also Kothe, “Tetrapolar Fungal Mating Types: Sexes by the Thousands,” 1996.

Tuttle et al., “Divergence and Functional Degradation of a Sex Chromosome-like Supergene,” 2016.

Cole, “The Evolution of Per-Cell Organelle Number,” 2016.

Lane, Transformer, 68, 2022. In fact Lane’s figure is “four football pitches,” which translates into about five American football fields.

“Obituary: Lynn Margulis,” 2011.

Sagan, Lynn Margulis: The Life and Legacy of a Scientific Rebel, 2012.

Margulis and Guerrero, “Two Plus Two Equals One: Individuals Emerge from Bacterial Communities,” 50, 1991.

Zell, “Oberon Zell – Master Wizard,” 2018, https://oberonzell.com/.

“The Grey School of Wizardry,” https://www.greyschool.net/.

In their 2021 book The Dawn of Everything, David Graeber and David Wengrow make the case that the American continent was a laboratory for social experimentation long before European colonists arrived, and indeed, that this tradition informed the United States’s founding Enlightenment ideals.

Wayland-Smith, Oneida: From Free Love Utopia to the Well-Set Table, 2016.

Nichols, Mary Lyndon, Or, Revelations of a Life: An Autobiography, 210–11, 1855.

Nichols, Esoteric Anthropology, 207–10, 1853.

Zell-Ravenheart, Green Egg Omelette: An Anthology of Art and Articles from the Legendary Pagan Journal, 2008.

Henrich, Heine, and Norenzayan, “The Weirdest People in the World?,” 2010; Henrich, Heine, and Norenzayan, “Most People Are Not WEIRD,” 2010; Henrich, Heine, and Norenzayan, “Beyond WEIRD: Towards a Broad-Based Behavioral Science,” 2010; Apicella, Norenzayan, and Henrich, “Beyond WEIRD: A Review of the Last Decade and a Look Ahead to the Global Laboratory of the Future,” 2020.

A phrase trademarked by TED Conferences, LLC, in 2015.

Zell-Ravenheart, “A Bouquet of Lovers: Strategies for Responsible Open Relationships,” 1990.

While Morning Glory was probably unaware of it, these Greek and Latin roots had been fancifully combined in print a few times before, though never in a way that stuck. For instance, on page 283 of Italian Futurist Tommaso Marinetti’s 1921 book L’alcòva d’acciaio: Romanzo vissuto, “Sono io che ti bevo e mangio tutta di baci minutissimi rapidissimi, Italia mia, donna-terra saporita, madre-amante, sorella-figlia, maestra d’ogni progresso e perfezione, poliamorosa - incestuosa, santa - infernale - divina!” Translation: “I am the one who drinks and eats you all with very small, very quick kisses, my Italy, delicious woman-land, mother-lover, sister-daughter, mistress of all progress and perfection, polyamorous - incestuous, holy - infernal - divine!”