Over the past fifty years, there’s been an explosion of gender and sexual minorities—lesbian, gay, bi, trans, queer, questioning, asexual, aromantic, and many more.

The LGBTQ+ rainbow is, unsurprisingly, most embraced by the young, more than a quarter of whom claim at least one of those letters. Even among older respondents, though, the survey suggests that significantly more people identify with a sexual minority than commonly cited statistics suggest. 1 The changes are especially dramatic among women. In this chapter, I’ll explore why that might be.

Before proceeding, though, a word about methodology and the slipperiness of definitions. As in the handedness analysis in Part I, “women” and “female” are used here as shorthand for those who answer “yes” to “Do you identify as female?” and “no” to “Do you identify as male?”; vice versa for “men.” This is not intended to suggest logical equivalence. We can be sure that, had the survey additionally asked “Are you a woman?,” a “yes” would usually—but not always—have been answered the same way as “Are you female?” Due to that “not always,” we can’t make assumptions about individuals without running roughshod over an excluded middle.

However, it’s still possible to meaningfully analyze differences between populations. The statistical findings distinguishing “men” from “women” in this book aren’t sensitive to the choice of criterion, because the excluded middle between these two populations remains a minority, as Chapter 14 will show. Graphs based on pronoun use, for example, look much the same. With appropriate care, inferences about populations can be made reliably, even if they’re based on approximate or noisy working definitions.

This statistical approach remains robust even when language and categories are a great deal blurrier. Much of Part III will be about population-level differences between people living in cities and in rural areas; with so many Americans living in the suburbs and so little standardization in terminology, this classification is hardly precise or binary. (Is Parker, Pennsylvania, population 695 according to the 2020 Census, really, per its official designation, a “city”?) Yet those differences can still be quantified and studied by focusing on changes as a function of a correlated variable—such as population density based on ZIP code, or self-reported answers to questions like “Do you live in the city?” Moreover, exploring these effects doesn’t require any commitment to rigid definitions of words like “city” or “rural.”

Now, let’s dive in.

Bisexuality, despite its frequent invisibility, accounts for well over half of the rainbow, over all ages. Women, in turn, make up the majority of the bisexual population, especially among the young.

Graphing female and male bisexuality separately reveals a striking difference. Roughly 5% of men are bisexual, with only modest variation by age. Among women, though, the variability is extraordinary. Nearly 34% of 19-year-old women are bi (about 1 in 3), but by age 66 it’s only about 2.15% (1 in 46). There are, in other words, about 15 times more 19-year-old bisexual women than 66-year-old bisexual women. Further, 4 out of 5 bisexual 19-year-olds are women, while only 1 in 3 bisexual 66-year-olds are.

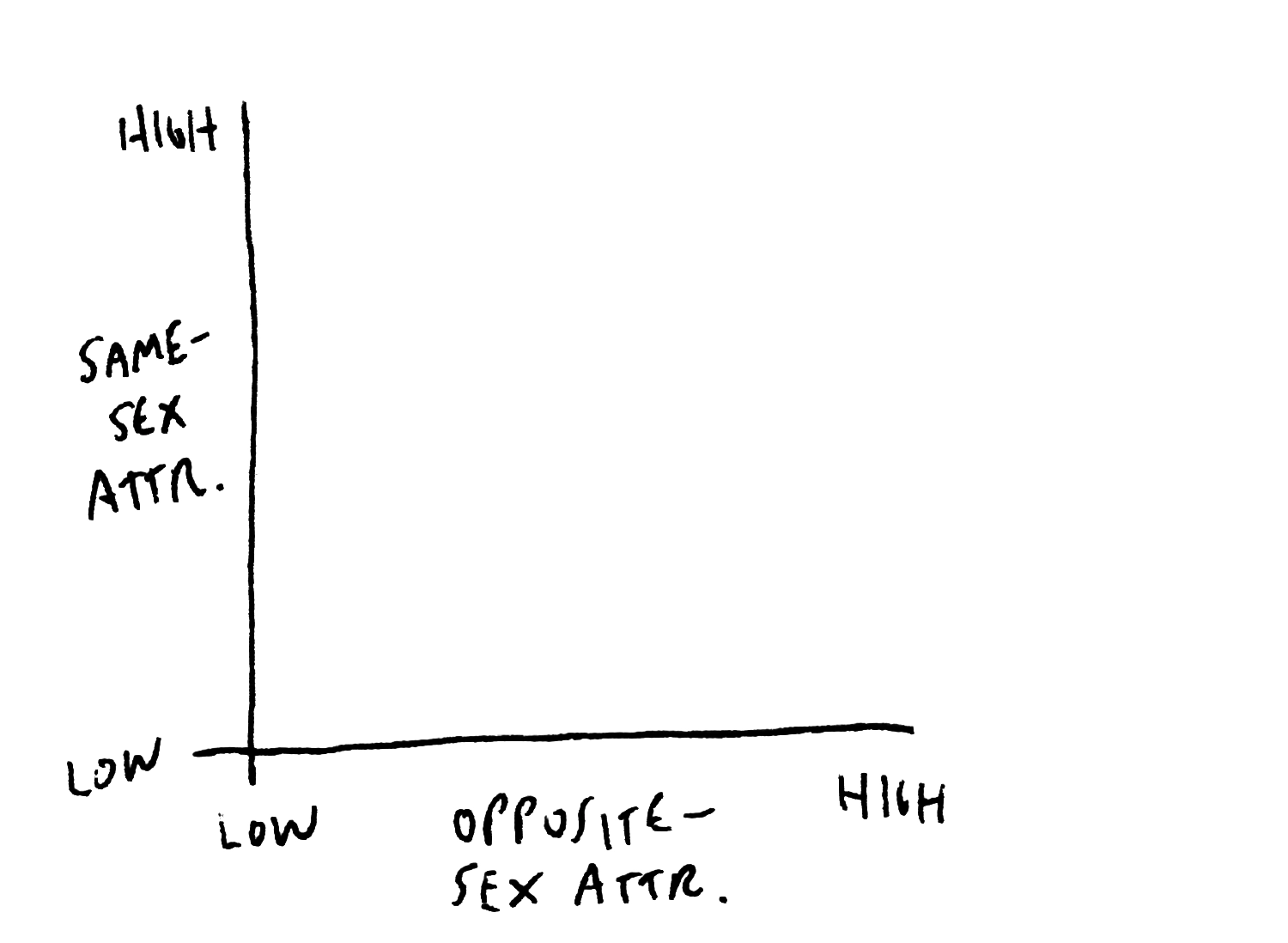

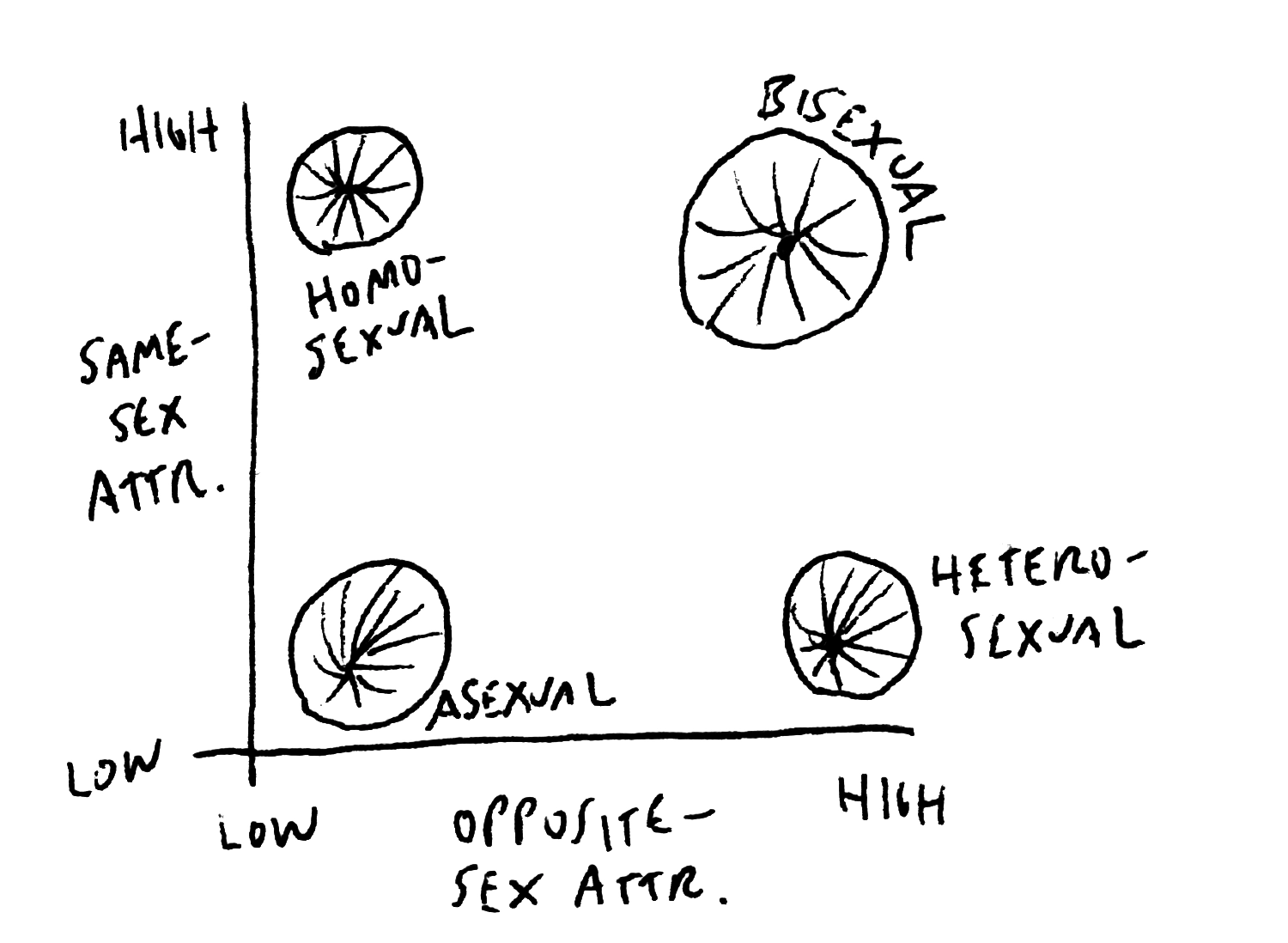

What to make of this? Thinking in terms of the Kinsey Scale, one might imagine that women are on average closer to the middle than men, that is, “more bisexual”; but this wouldn’t explain why there’s such an impressive change in women’s bisexuality as a function of age. In theory, this change could be age-related; perhaps something about women’s physiology, more so than men’s, changes as they age?

Remember, this “age hypothesis” is testable simply by comparing the 2018–19 data with the 2020–21 data. Although the error bars are large, the percentages appear to be in flux, which isn’t consistent with the age hypothesis.

Among women across a wide range of ages, bisexuality has risen by somewhere between 1% and 4%—probably a significant change, but not dramatic. A rise in bisexuality is also evident among men across all ages. Although the absolute increase is only a bit larger, it’s much larger in relative terms, since fewer men are bisexual to begin with; around age 45, a 5% change has amounted to a doubling in the number of bisexual men.

Here are four potential factors explaining the discrepancy between bisexuality in women and in men:

Maybe women are more flexible in their sexual attraction than men, resulting in a far greater proportion of younger women identifying as bisexual.

Maybe male bisexuality carries a greater stigma than female bisexuality at all ages, resulting in only a fraction of potentially bisexual men acknowledging their bisexuality—though over time, the stigma for men is decreasing. Absent uneven stigma, the curves for women and for men might look more alike.

Maybe, even if women aren’t inherently more flexible than men, they have been forced to compromise more—that is, exercise whatever flexibility they have—especially in the past, due to social and economic disadvantage.

Maybe female sexuality as a whole has been systematically devalued, especially in the past, resulting in lower expectations of sexual attraction and pleasure.

Evidence supports all four factors. 2 This chapter focuses on sexual flexibility and stigma—numbers one and two above—since the techniques I’ve introduced offer several ways to see these effects, and the implications are both interesting and wide-ranging. In particular, sexual flexibility bears on the question of essential nature versus “lifestyle choice”—that is, free will—broached in the previous chapter. The next chapter will delve into the third and fourth factors, exploring gender asymmetries in the role of economics and in societal expectations about sexual fulfillment.

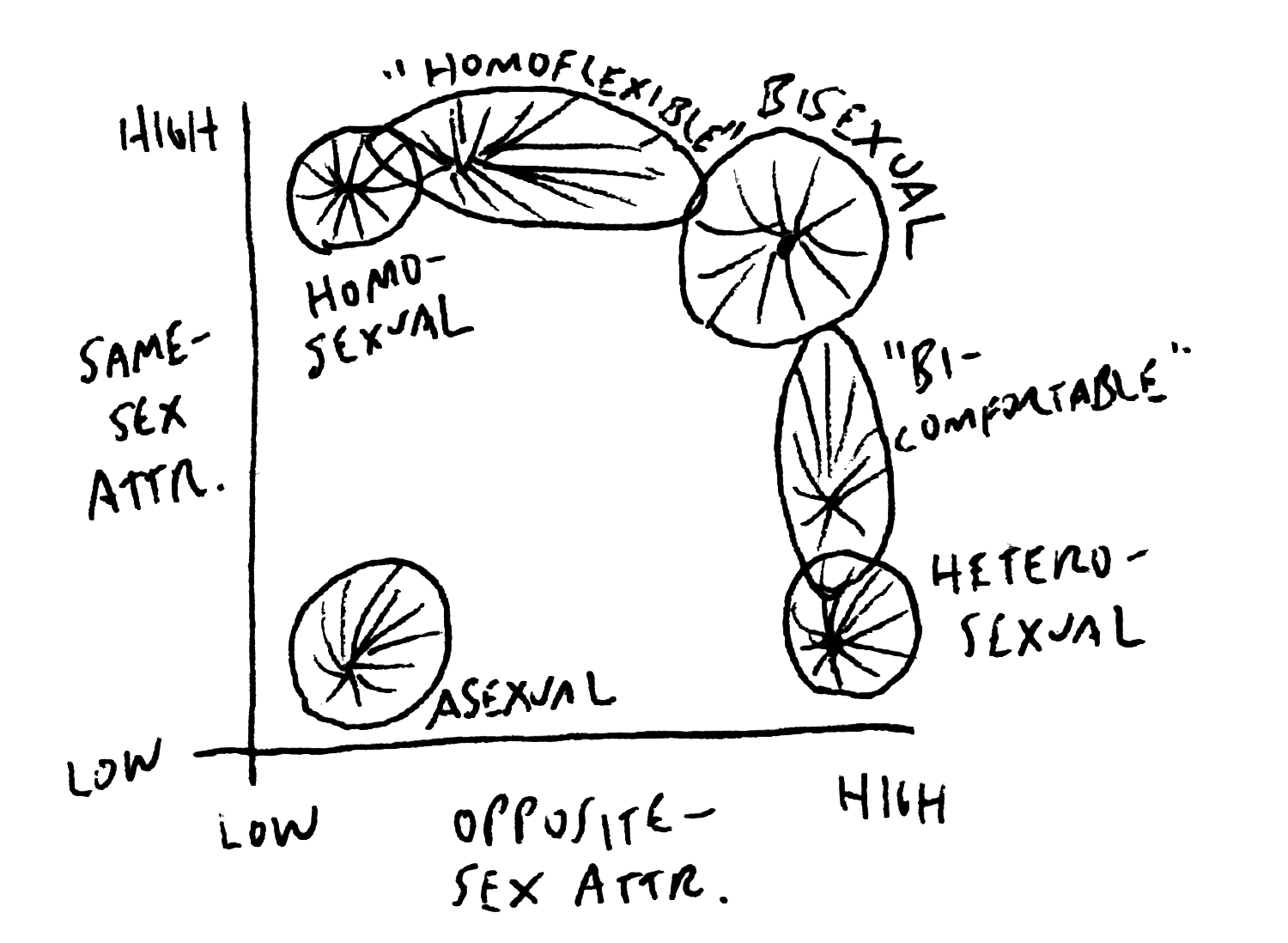

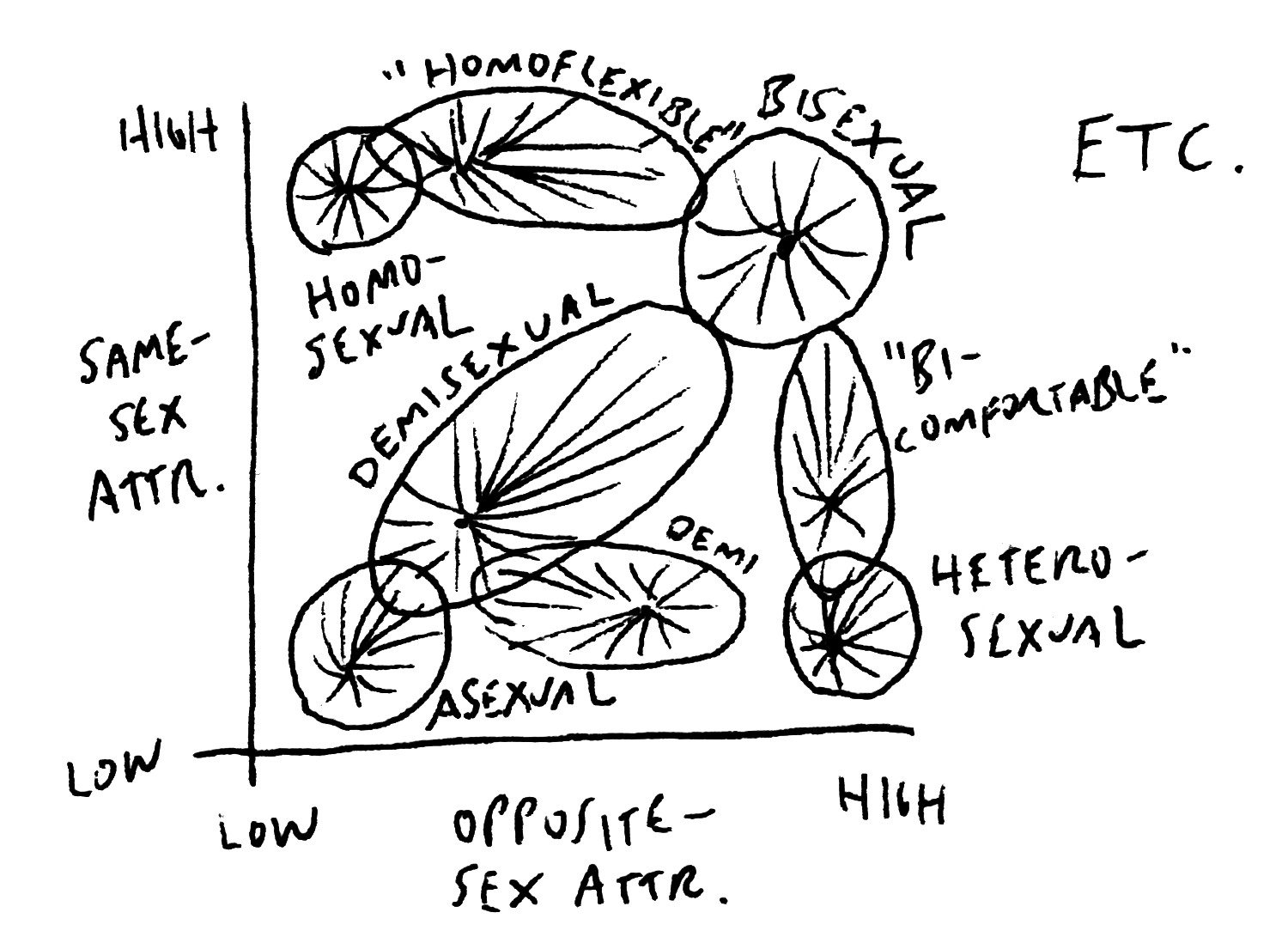

Flexibility cannot be fully described using a single point on the one-dimensional Kinsey Scale, or even the two-dimensional “Kinsey diagram”—yet another limitation of those models. The 2D model can be extended, though, to imagine a person as being tethered to a “home position” on the diagram by a spring, which might be tight or loose, or perhaps even loose in one direction (say, attraction to the same sex) but tight along another (say, attraction to the opposite sex). A highly flexible person may live in an entire fuzzy region of the Kinsey diagram.

Most people seem to have some flexibility in their sexual “wiring,” allowing them to adapt to varying environments. Studies have documented this kind of flexibility, for example, among otherwise heterosexual men in prisons, on naval ships, and under other prolonged single-sex living conditions. 3 It’s also common for gay and lesbian people to have a history of early opposite-sex relationships before coming out, and while those early relationships may not have been entirely satisfying, they imply some flexibility too.

The survey comments include many accounts of sexual flexibility, but, as the numbers also show, they’re a lot more frequent among women, regardless of whether they identify as straight, lesbian, bi or pan, or otherwise:

There were a couple questions that may seem contradictory, to clarify: I am both hetero and bi, a little bit… Meaning I’m not like fully bisexual because it’s only a physical attraction towards women sometimes. I would consider myself more “bi-comfortable” than bisexual, if that makes sense. 4

I have had homosexual and bisexual experiences and attractions to women in the past. I consider myself heterosexual, but could change my mind if the right woman came along. 5

I am mostly lesbian, but once in a blue moon I am attracted to a man. It doesn’t happen often enough for me to consider myself bisexual, but it happens. 6

One implication is that many women with male partners (including ones who think of themselves as straight) easily could have been bisexual or pansexual, or even lesbian, had they grown up without the pressure to conform to heteronormative expectations—reminiscent of the way many people whose behaviors suggest they’re ambiguously handed seem to have taken the path of least resistance to become right-handed. Comments from 20- to 40-year-old women offer many examples:

I am a slightly closeted bisexual woman who is happily married to a man. 7

I consider myself bisexual because I am attracted to both men and women, but I’ve only ever dated men. 8

I’m bisexual, married to a man, living a hetero-normative life. 9

Bisexual but in a heterosexual partnership. 10

Bisexual, don’t show it much. 11

Closeted bisexual. 12

I guess I could be classified as bisexual because I am physically attracted to women. But have never acted on it and doubt I ever will. 13

I don’t identify as bisexual, but find myself attracted to women. 14

These sentiments are so common, it can almost make one wonder whether truly exclusively opposite-sex attracted women might be a rarity, as one less flexible 33-year-old from Kennesaw, Georgia, wryly points out:

It seems like everyone is so touchy [nowadays] about their sexuality, and it [seems] like women are supposed to be attracted to other women. but I’m not, [it’s] almost confusing.

This comment implicitly observes that, as with other sexual minorities, same-sex attraction and bisexuality are much less stigmatized now than they used to be—especially for women, among young people, and (as Part III will show) in cities. A 38-year-old woman in San Francisco, a city famous for its progressive attitude to sex, celebrated this in her response, writing,

I was born female and have always identified as a heterosexual woman. But I am very blessed to live in a city/community that is the most diverse, open, and beautiful in this world and I feel so very lucky to live [in] a place where everyone is allowed to be who they truly are in every sense.

It’s still worth remembering that this isn’t always the felt reality, though. A fellow resident demurred,

I consider myself heterosexual because I don’t want to deal with being gay or bisexual in our current society, but every once in a while I’ll be attracted to another woman. I suppose that could make me bisexual then, but I don’t really consider myself that.

Given these are the sentiments of a 32-year-old woman who also lives in San Francisco, it’s easy to imagine that for an older man in a more conservative rural ZIP code, the closet is still the norm.

The recent and contentious idea of “demisexuality” can be understood as another manifestation of sexual flexibility. Per Wikipedia,

The term ‘demisexual’ comes from the concept being described as being “halfway between” sexual and asexual. […] A demisexual person does not experience sexual attraction until they have formed a strong emotional connection with a prospective partner. The definition of “emotional bond” varies from person to person. Demisexuals can have any romantic orientation. People in the asexual spectrum communities often switch labels throughout their lives, and fluidity in orientation and identity is a common attitude. 15

The apparent vagueness of demisexuality as a phenomenon or identity has attracted a certain amount of ridicule in some quarters, especially considering the ever-lengthening “alphabet soup” of finely parsed LGBTQ+ identities. Is a lack of lust for anyone you haven’t bonded with emotionally really a sexual minority deserving of a letter, like being lesbian or gay—or is it just, to use a contentious word, “normal”? On the other side of the coin, some feminist critics argue that demisexuality whiffs of a patriarchal fantasy: a woman being reluctantly wooed by a man, awakening sexually to her suitor only once she has been “made” to fall in love. Whichever way one feels about such stories, it’s undeniable that they sell—and men aren’t the main audience.

More to the point, though, claiming that there’s no such thing as demisexuality is a stretch when so many people say that they’re demisexual: between 2% and 5% of men, and between 5% and 10% of women. To assert that one “doesn’t believe in” demisexuality is like saying one “doesn’t believe in” ambidexterity, whether because vanishingly few people are “truly” ambidextrous or because nearly all of us are, a little bit. Here, as elsewhere, we should listen to what people are telling us about themselves, and follow the data where it leads.

Recall that asexuality is more common among women than men. I’ve also hypothesized that women tend to be, on average, more flexible in their sexuality than men. So, it’s unsurprising to find that demisexuality is more common among women too, since demisexuality can be thought of as an asexual anchor point along with a high degree of flexibility. This is consistent with the usual self-description of people who identify as demisexual: asexual by default, but able to become more sexual under the “right” circumstances, and with the “right” partner.

The way asexuality and bisexuality are neighbors on the 2D Kinsey diagram might also shed light on why demisexual people are often fluid in their orientation. For example, a 27-year-old woman from Batavia, New York, wrote, “I identify as demisexual and have only had relationships with men, but that doesn’t mean I’d be opposed to a relationship with a woman.”

In comparing the percentage of women who are lesbian with the percentage of men who are gay, more evidence emerges of greater sexual flexibility among women and also, perhaps, of greater stigma among same-sex attracted men.

Notice that the percentage of men who are gay at different ages only varies by a bit over a factor of two, from a high of 10% around age 22 to a low of 4-5% among the youngest and the oldest adults in the sample. It’s reasonable to suppose that about 5% of men are so unambiguously gay that they identify that way regardless of which generation they belong to, which is to say, despite the inexperience of younger men, and the greater stigma experienced by older men. It seems that an additional 5% or so of young men who don’t identify as gay at age 19 decide that they are by their early twenties, which suggests a greater degree of flexibility among this group; in earlier generations, when the stigma was stronger, many of them likely would never have identified as gay.

By contrast, lesbians only comprise about 2.5% of 66-year-old women (1 in 40). Yet among young women, lesbian identification rises to 20% (1 in 5), a factor of eight higher! The curious result is that older lesbians are half as common as older gay men, while 19-year-old lesbians are four times more common than 19-year-old gay men.

Comparing the proportion of gay men who are exclusively same-sex attracted 16 with the proportion of lesbian women who are exclusively same-sex attracted reveals further evidence supporting the case for women being more flexible.

Only 25% or so of young lesbians are exclusively same-sex attracted, implying some combination of sexual flexibility and a broader umbrella for lesbian identity, as one would expect given lower stigma nowadays. Among the (much smaller) population of 66-year-old lesbians, though, nearly 90% are exclusively same-sex attracted; most of them presumably felt no ambiguity or flexibility, and would have had the greatest trouble conforming to heterosexual expectations in a repressive environment. (Many, in fact, grew up in just such an environment.) On the other hand, a majority of gay men of all ages, roughly 60-80%, are exclusively same-sex attracted, with the lowest proportion around age 22, coinciding with the peak in gay male identification.

Recall, from the graphs at the end of Part I of this book, that percentages of women and men who are exclusively same-sex attracted show far less variability, both by age and by gender, than the percentages identifying as lesbian and gay. Even in the same-sex attraction graphs, though, there’s some evidence of greater female flexibility; the range for exclusive same-sex attraction among women varies from a low of about 2.5% above age 50 up to nearly 6% at age 21 (a 2.4x difference), whereas among men it doesn’t vary as much by age, ranging from about 3.5% to about 5% (a 1.4x difference).

Under the age of 40, the percentages of exclusively same-sex attracted women and men look very similar. This is interesting in that it suggests far less of a difference between male and female same-sex attraction once we look beyond the evolving meanings (and differing stigmas) of terms like “lesbian” and “gay.” While you’ve hopefully been convinced by now that it’s unwise to speculate on what humanity in “a state of nature” might look like (remember natureculture: the inseparability of nature and culture), the numbers among the young are probably less distorted by historical stigma or economic privilege.

Whew, that’s a lot of graphs.

To sum up the picture so far: with less social stigma, more men might be gay or “heteroflexible,” or put another way, women’s apparently greater flexibility is at least partly a function of the lower stigma surrounding female same-sex attraction.

The National Bureau of Economic Research has concluded that the non-heterosexual population has been significantly underestimated in surveys using traditional questioning methods, even if anonymous. Coffman, Coffman, and Ericson, “The Size of the LGBT Population and the Magnitude of Antigay Sentiment Are Substantially Underestimated,” 2017.

This isn’t an exhaustive list of potential factors, just the ones for which I have evidence based on the survey data. For example, it’s also conceivable that sexual attraction varies more as a function of age in women than in men for physiological reasons (to be clear: no evidence I’m aware of supports this idea).

Hensley and Tewksbury, “Inmate-to-Inmate Prison Sexuality: A Review of Empirical Studies,” 2002.

A 29-year-old woman from Bargersville, Indiana.

A 40-year-old woman from Dallas, Texas.

A 37-year-old woman from Austin, Texas.

A 26-year-old woman from Eureka Springs, Arkansas.

A 39-year-old woman from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

A 34-year-old woman from Thomson, Georgia.

A 29-year-old woman from Huntersville, North Carolina.

A 21-year-old woman from Rensselaer, New York.

A 34-year-old woman from Winnetka, California.

A 35-year-old woman.

A 36-year-old woman from Westland, Michigan.

Wikipedia, “Gray asexuality,” 2021.

These calculations are based on both sexual and romantic attraction. Exclusive same-sex attraction here means “yes” to both sexual and romantic attraction to the same sex, and “no” to the opposite sex. As in other plots where numbers are broken down by binary gender, people whose gender identification is ambiguous are left out of the analysis.