The reclamation of the umbrella term “queer” in recent years is partly a response to the ever-thickening LGBTQ+ alphabet soup—an effort to create more solidarity across that archipelago of minority identities. This reclamation coincides with a sharp rise in queer identification among the young, plainly visible even between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

Queer generally means “not on the mainland.” It says, “I don’t conform.” But it’s also an acknowledgment that sexual flexibility and other kinds of fluidity can render some of those fine alphabetic distinctions tenuous, at least as a stable basis for identity: “I’m queer and categories don’t fit and sometimes answers sound conflicting when they aren’t.” 1

Queerness has become disproportionately common among younger women—under the age of 30, about two thirds of queer people are women, about a quarter are men, and about 10% identify as both or neither, whereas above middle age roughly equal numbers of queer people are women and men, with a negligible number of people (queer or not) identifying as both or neither.

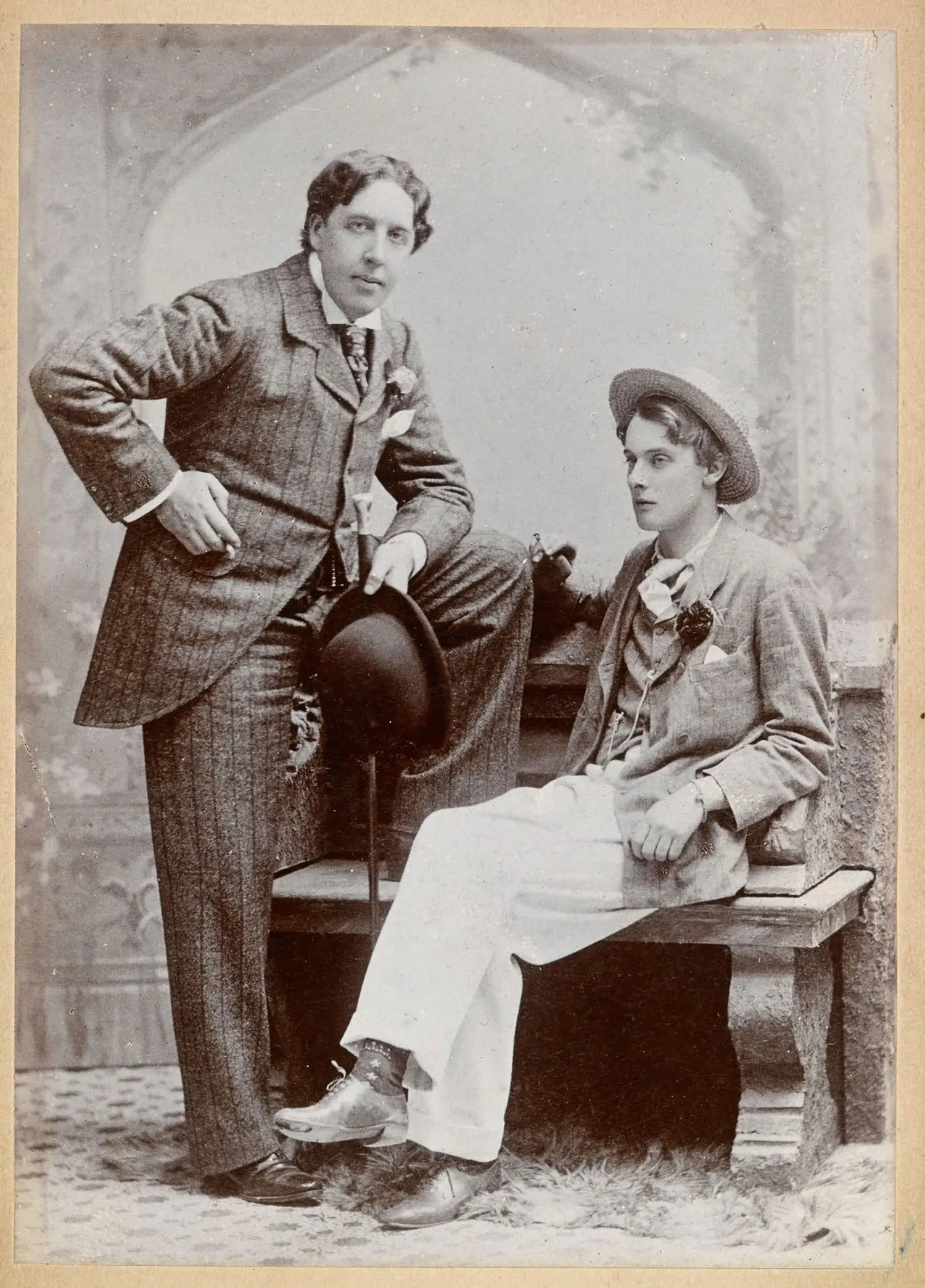

Where did the term come from? In its older sense, it meant unnatural or off-kilter, and usually not in a good way. By the end of the 19th century, “queer” had also become a slur referring specifically to gay and lesbian people. This usage is often traced to John Sholto Douglas, the 9th Marquess of Queensbury (1844–1900), a boxing enthusiast and inveterate bully whose sons had love affairs with other men, much to Queensbury’s disgust. 2 The eldest son, Francis, was engaged as a private secretary (with… benefits) to Archibald Primrose, the 5th Earl of Rosebery, who briefly served as the Prime Minister of the UK in 1894–95. When Francis died under suspicious circumstances at a shooting party, Queensbury sent an enraged letter to his younger son, Alfred, blaming the death on “Snob Queers like Rosebery.” 3

The survey shows how the meaning of “queer” in the US has continued to shift in more recent history. 4 While three quarters of queer people over the age of 50 identify as “homosexual, gay or lesbian,” 5 this figure drops to around half among younger people. At the same time, older lesbians and gay people are somewhat less likely to identify as queer—not so much because they don’t believe the word was intended to apply to them, but because many still find it offensive, hence reject the usage. As a 59-year-old man from Jacksonville, Florida, put it, “I identify as homosexual or gay, but not queer.”

Studying the same pattern with respect to bisexuality offers further evidence of the way “queer” has become more inclusive and less offensive over time. Among the young, nearly 60% of queer people are bisexual, while less than 30% of queer people older than 55 are bi. Conversely, while 40% of the 21-year-old bisexual population consider themselves queer, fewer than 15% of bisexuals over the age of 50 do.

There’s more going on here than a mere shift in language. Most older lesbian, gay, and bisexual people seem to have less use for the flexibility implied by the term “queer,” because while fewer in number, a greater proportion are (and, typically, always were) among the least flexible: unwilling or unable to conform to heterosexual expectations even at a time when the social pressure to do so was far more intense than it is for young people today.

The previous chapter made the case that women tend to be more sexually flexible, or adaptable, than men, and that the stigma associated with same-sex attraction seems to be easing. Before accepting this as a sufficient explanation for the upward trends in same-sex attraction among women, though, it’s important to take stock of the economic picture. After all, stigma isn’t the only mechanism by which social pressure can force “who we are” to conform to a societal norm. Lack of resources can constrain us just as powerfully.

Recall the income data from Chapter 4, showing how much less money women used to make than men (an earnings gap that still hasn’t closed). Their lower expected earnings strongly incent women to marry men, and stay married to them, especially if they’re committed to the costly project of raising children. Many women might make this choice even if they’re far from heterosexual—and perhaps even if they’re not particularly flexible. These economic considerations didn’t escape the notice of Edmund Bergler, who set aside a chapter on lesbianism in his 1956 book, writing:

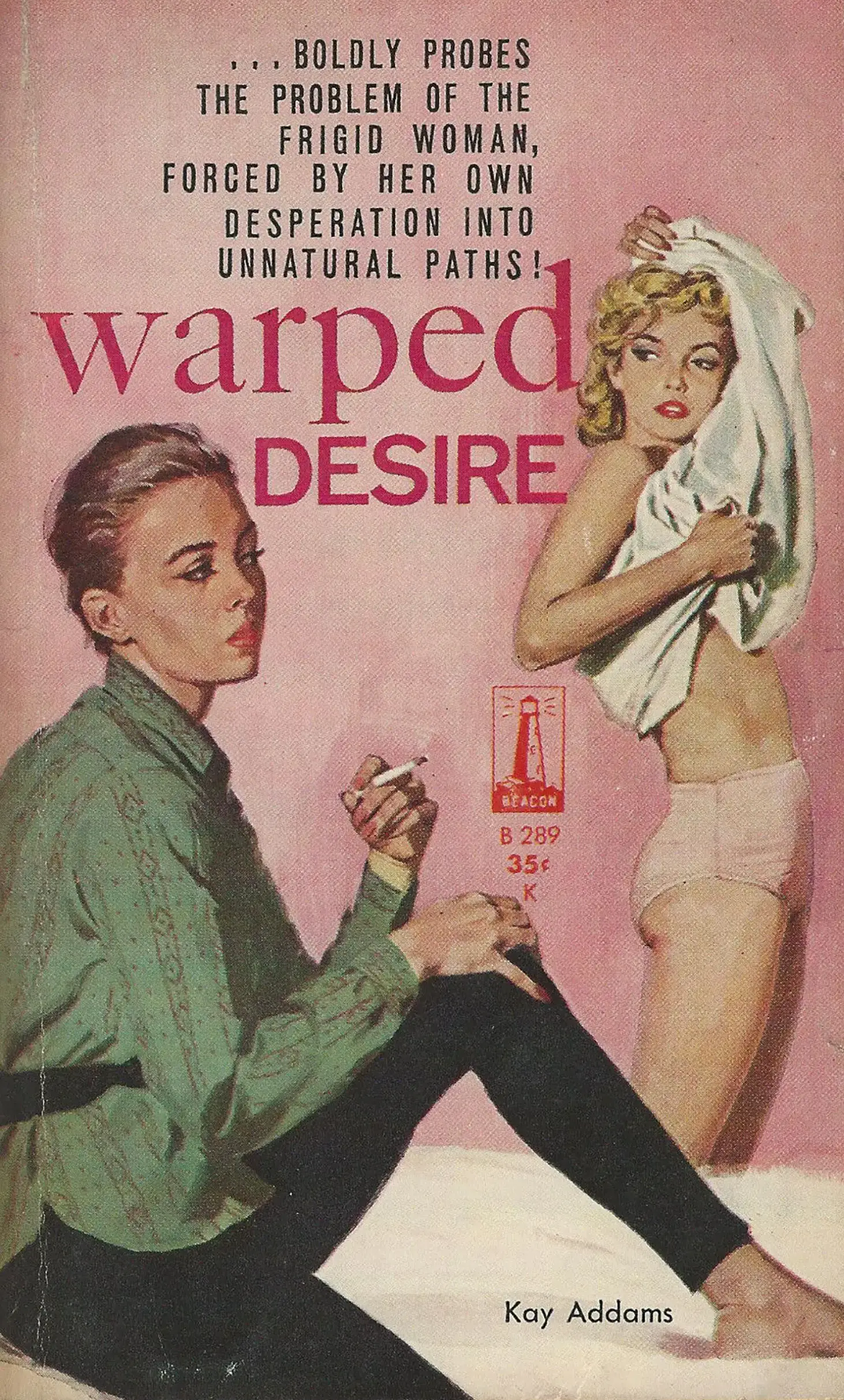

The ratio of visible to camouflaged Lesbians is probably one to one hundred, and most of the camouflaged Lesbians are married. […] Male homosexuals habitually overplay, female homosexuals habitually underplay the perversion. […] [F]emale homosexuals of the majority group (those who have married for social or economic reasons) […] tend to “prove” that the whole thing is child’s play, for aren’t they married? […] In observing and studying women patients for nearly thirty years, I have always been amazed at the frequency with which one finds protracted or sporadic, transitory Lesbian episodes in the histories of frigid women. 6

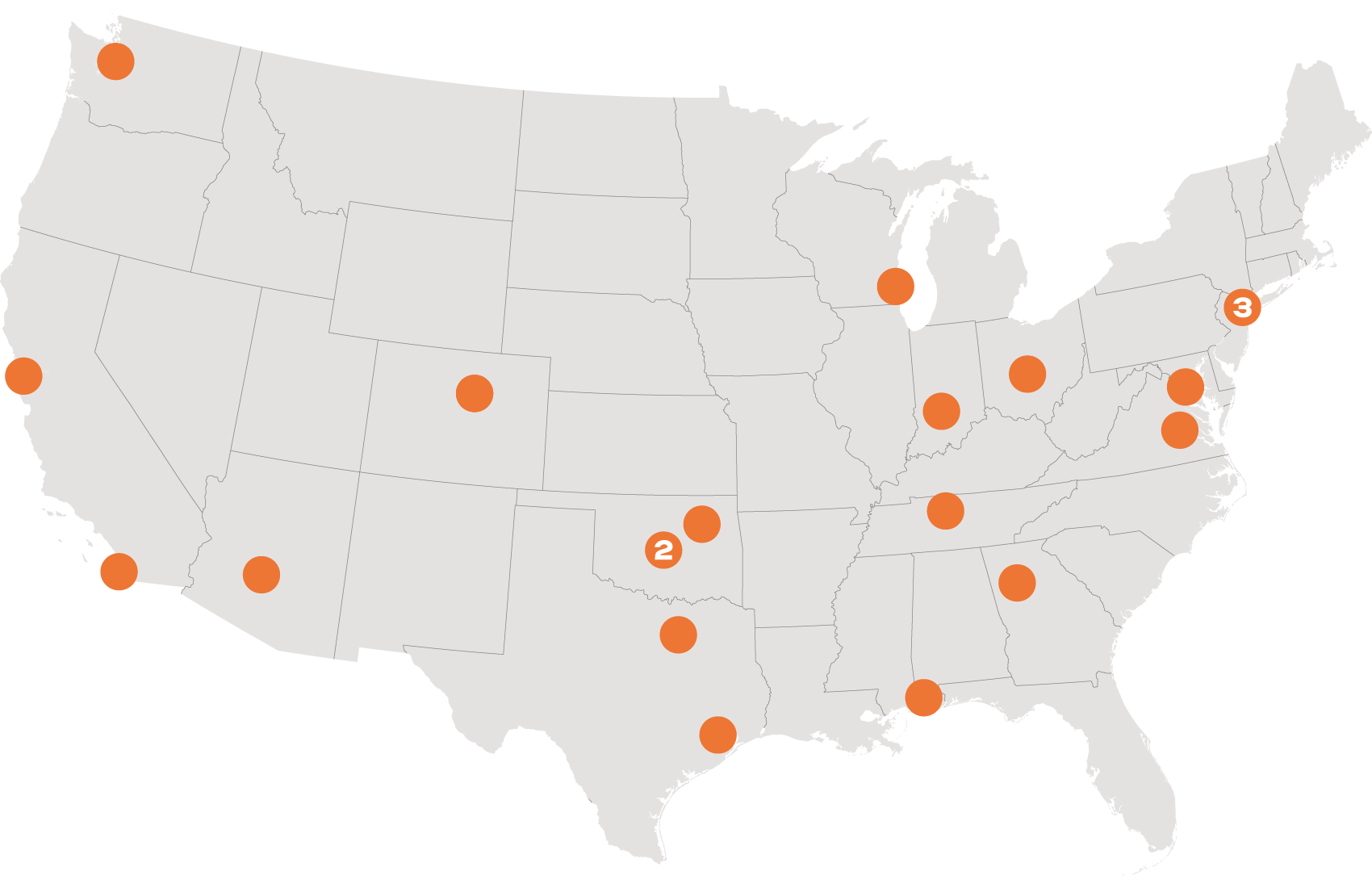

Washington

Wisconsin

New

York

Ohio

Illinois

Indiana

Tennessee

Colorado

California

Virginia

Arizona

Oklahoma

Georgia

Alabama

Texas

Beyond issues of economic privilege, expectations have also shifted over time regarding female sexual pleasure. The fact that leading 20th century psychiatrists like Sigmund Freud, Wilhelm Stekel, and Edmund Bergler considered “frigidity” in women a problem (Stekel wrote a two-volume monograph on the subject 10 ) represented progress of a sort, as a pervasive belief in the 19th century had been that women didn’t, or shouldn’t, actually enjoy sex.

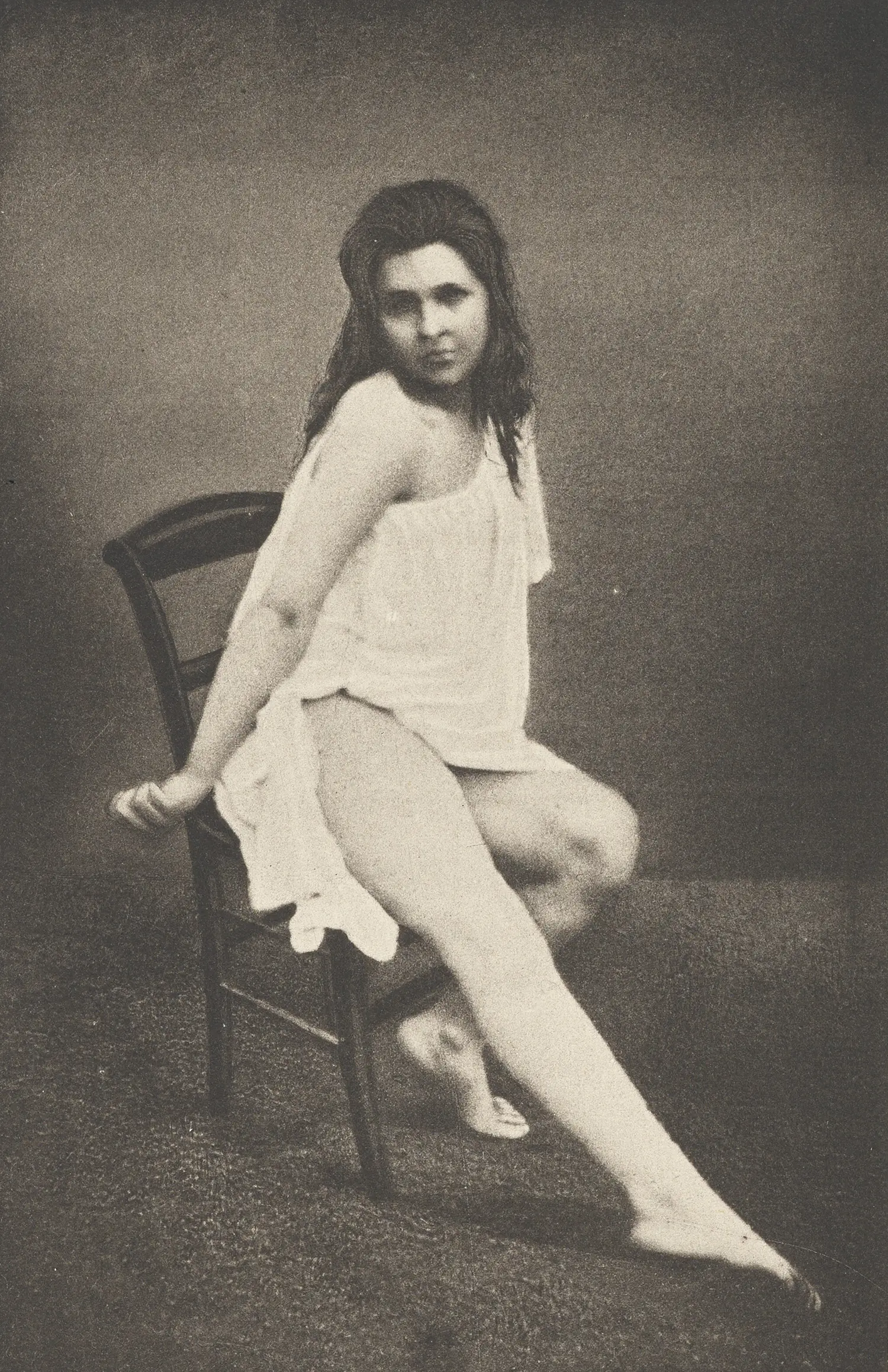

British medical doctor and author William Acton (1813–1875) was a towering figure during this earlier period. His book The Functions and Disorders of the Reproductive Organs in Childhood, Youth, Adult Age, and Advanced Life, Considered in Their Physiological, Social, and Moral Relations was an international bestseller, going through dozens of editions and reprintings in London and Philadelphia from 1857 until 1903, more than a quarter century after his death. The Lancet and other prominent medical journals of the day were effusive in their praise. The following is from the third edition, printed in London in 1867:

[The] majority of women (happily for them) are not very much troubled with sexual feeling of any kind. What men are habitually, women are only exceptionally. It is too true, I admit, as the divorce courts show, that there are some few women who have sexual desires so strong that they surpass those of men, and shock public feeling by their exhibition. I admit, of course, the existence of sexual excitement terminating in nymphomania,* a form of insanity that those accustomed to visit lunatic asylums must be fully conversant with; but, with these sad exceptions, there can be no doubt that sexual feeling in the female is in abeyance, and that it requires positive and considerable excitement to be roused at all; and even if roused (which in many instances it never can be) is very moderate compared with that of the male. 11

The footnote on “nymphomania” is perhaps even more remarkable, in that it spells out the potential consequences for a woman who admits to too much sexual pleasure:

*I shall probably have no other opportunity of noticing that, as excision of the clitoris has been recommended for the cure of this complaint, Kobelt thinks that it would not be necessary to remove the whole of the clitoris in nymphomania, the same results (that is destruction of veneral desire) would follow if the glans clitoridis had been alone removed, as it is now considered that it is in the glans alone in which the sensitive nerves expand. This view I do not agree with […].

Acton, in other words, wasn’t content to cut off the exposed tip of the clitoris to “treat” cases of excessive female pleasure, but felt it necessary to excise “the whole” organ 12 in order to extinguish sexual pleasure—the same reason female genital mutilation is still practiced in some places today. On the other side of the pond, America’s most famous doctor, the KFC-looking John Harvey Kellogg (of breakfast cereal fame), recommended the same procedure for the “treatment” of masturbation in girls. In his doomed quest to eradicate lustful urges and “self abuse” by means of wholesome grains, cereals, and genital mutilation, Kellogg was inspired by temperance preacher Sylvester Graham (of Graham cracker fame) and in turn inspired Charles William Post (of competing breakfast cereal fame). To my knowledge, no other country’s contributions to the culinary arts were so deliberately designed to suck the joy out of life. 13

Returning to economics, what Acton had to say about the role of social class in female sexual desire is noteworthy too:

[Y]oung men […] form their ideas of women’s feelings from what they notice early in life among loose or, at least, low and vulgar women. There is always a certain number of females who, though not ostensibly in the rank of prostitutes, make a kind of trade of a pretty face. […] Any susceptible boy is easily led to believe […] that she, and therefore all women, must have at least as strong passions as himself. Such women, however, will give a very false idea of the condition of female sexual feeling in general.

Association with the loose women of London streets, in casinos, and other immoral haunts (who, if they have not sexual feeling, counterfeit it so well that the novice does not suspect but that it is genuine), all seem to corroborate an early impression such as this, and […] it is from these erroneous notions that so many young men think that the marital duties they will have to undertake are beyond their exhausted strength, and from this reason dread and avoid marriage.

Married men—medical men—or married women themselves, would tell a very different tale, and vindicate female nature from the vile aspersions cast on it by the abandoned conduct and ungoverned lusts of a few of its worst examples. […] The best mothers, wives, and managers of households, know little or nothing of sexual indulgences. Love of home, children, and domestic duties, are the only passions they feel.*

As a general rule, a modest woman […] submits to her husband, but only to please him; and, but for the desire of maternity, would far rather be relieved from his attentions. 14

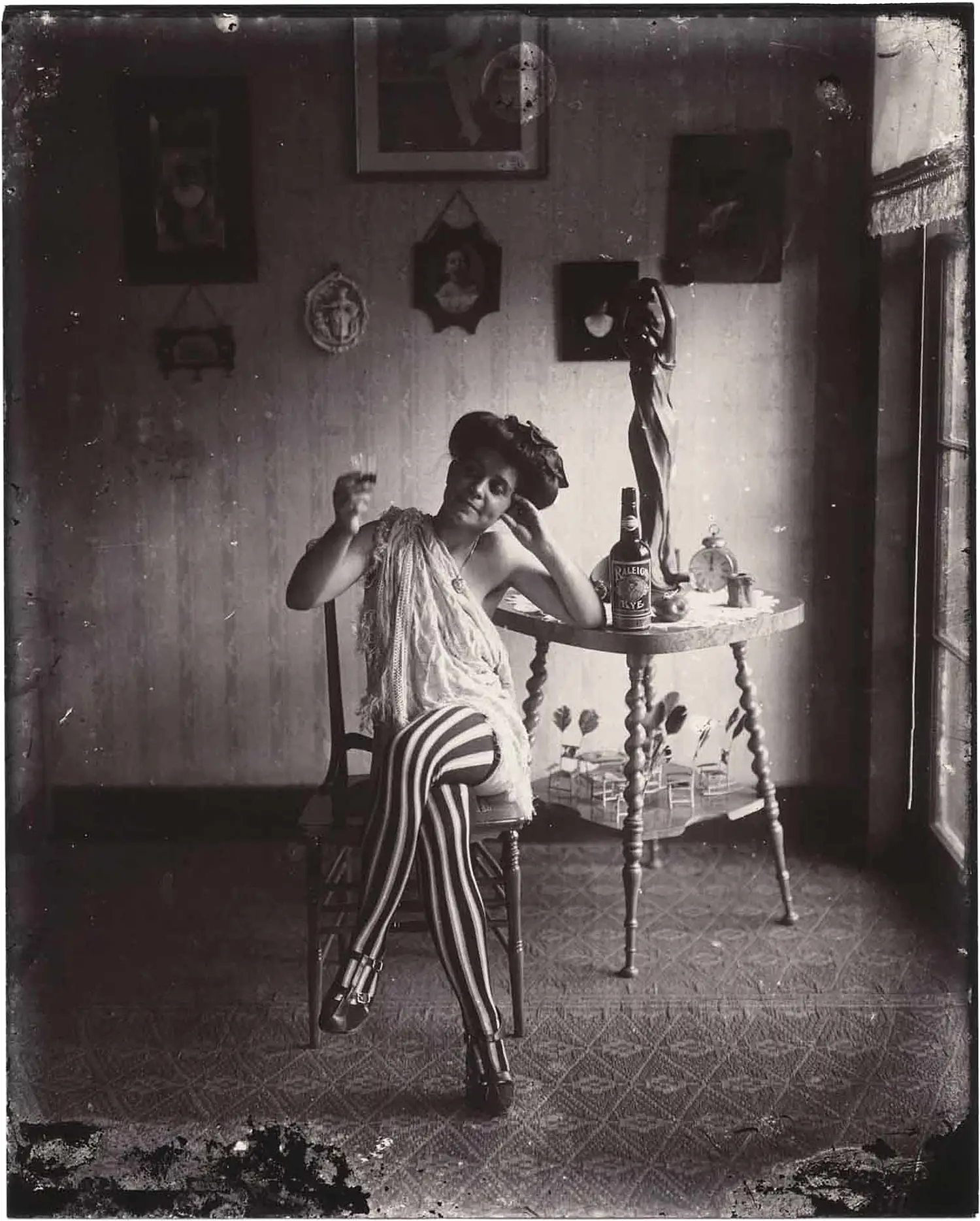

The association of lust with poverty hints none too subtly that Acton imagined the Great Chain of Being to be reflected in the social order, with the upper classes more angelic in their pursuits, while the “low and vulgar” rutted like animals. There’s something self-fulfilling in this grim picture. It’s undoubtedly true that some lower-class women feigned or exaggerated sexual interest in order to secure support from wealthier men. Given the marginal economic prospects for a single working-class urban woman in the 19th century, this would have offered a route, albeit a precarious one, to better prospects—and it must have made the line between professional sex work and mere “survival while female” somewhat blurry, as it often has been under patriarchy.

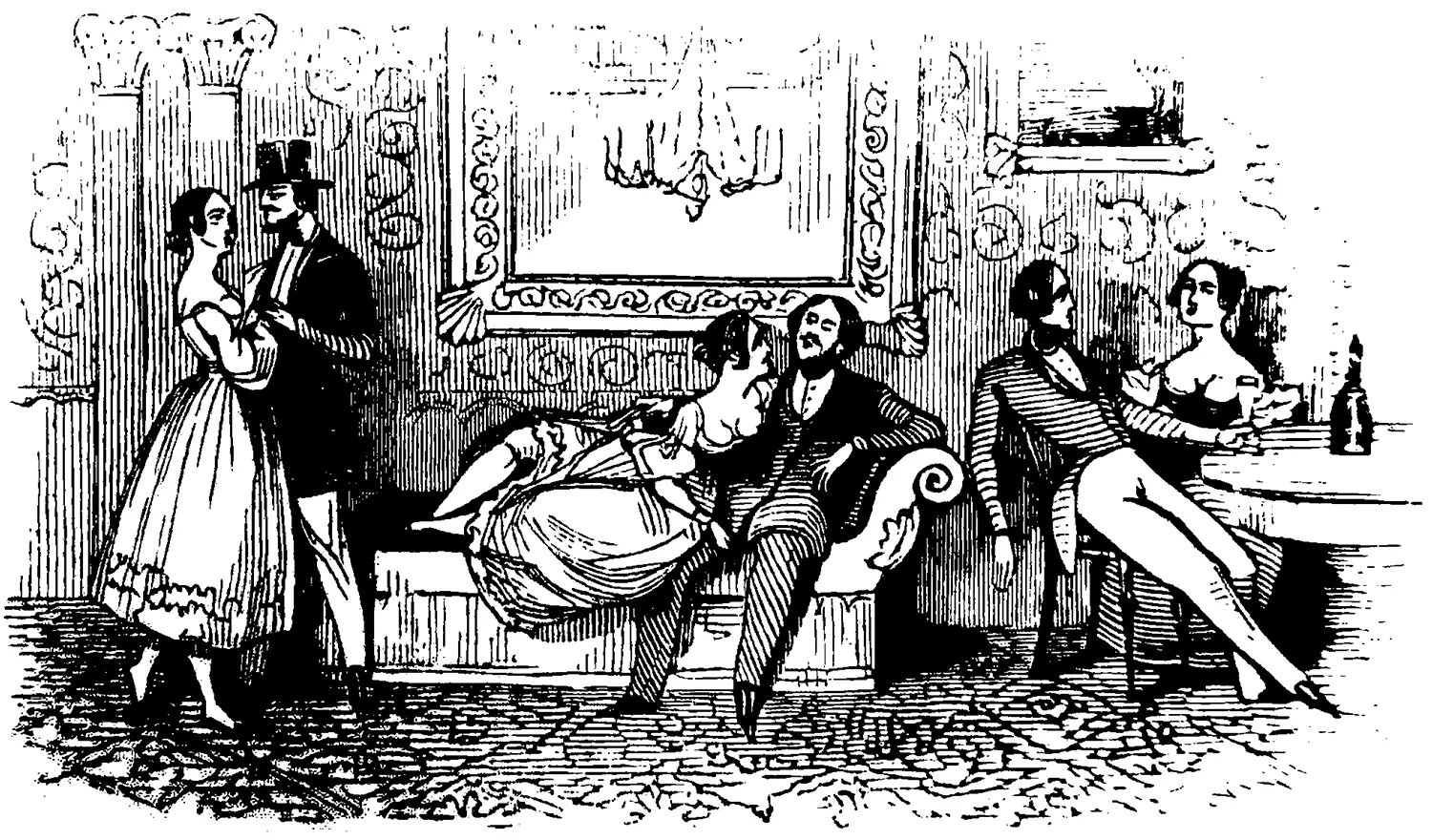

The sex trade did in fact flourish in this age of extreme repression, rapid urbanization, and rising economic inequality. According to an 1857 article in The Lancet, there were 80,000 sex workers and 5,000 brothels in London (“one house in sixty”), 15 generating a torrent of lurid reportage and hand-wringing policy debates among clergy, politicians, doctors, lawyers, reformers, and moralizers—many of whom, being older, male, and moneyed, were undoubtedly also regular clients.

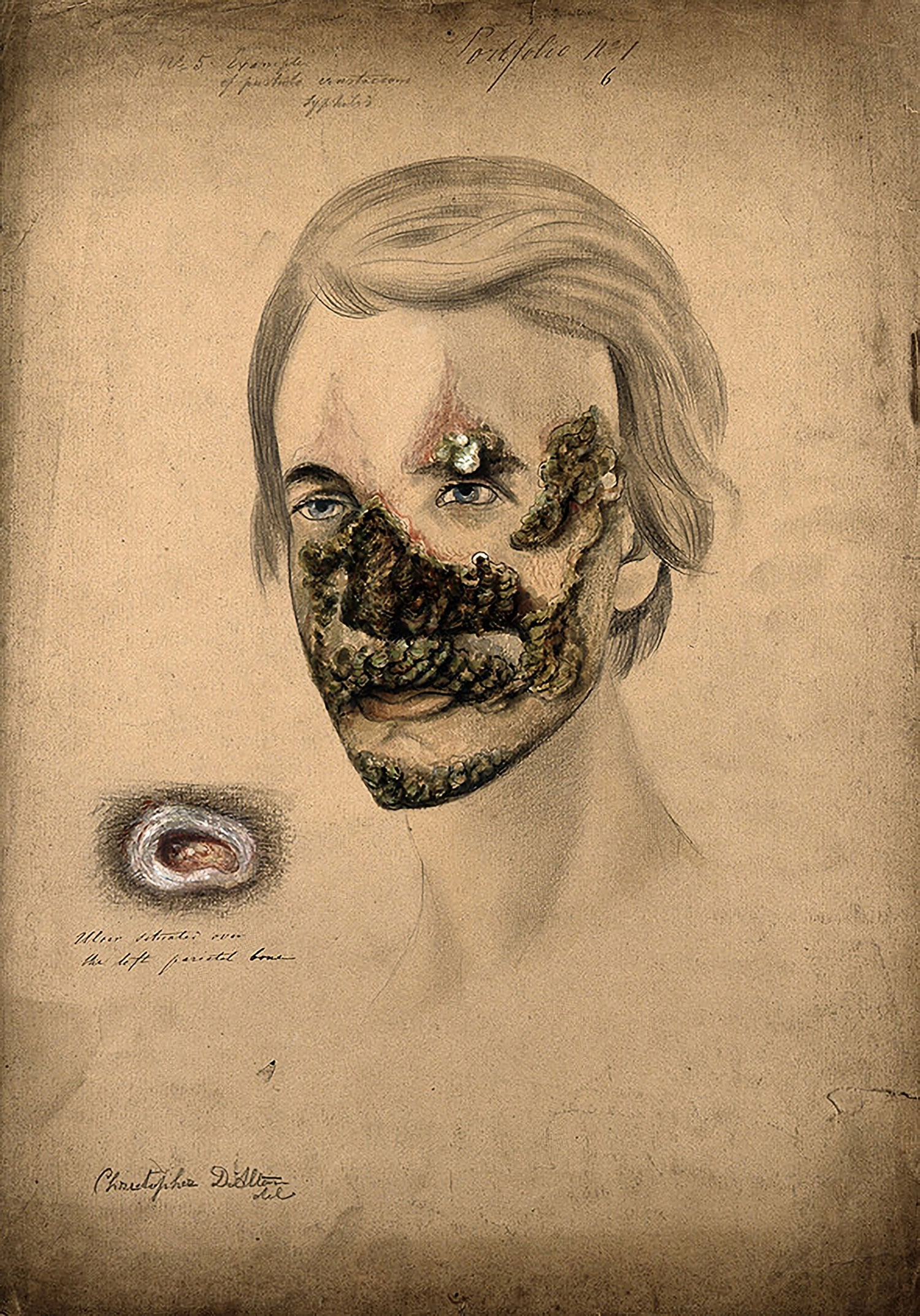

With no antibiotics and scant use of condoms (for these were still primitive and costly), epidemic waves of syphilis and other “social diseases” swept through the cities, disfiguring, sterilizing, and sometimes killing poor and rich alike. Artwork of this period often reprised, in a sexier key, the danse macabre (or dance of death) themes popularized in earlier centuries during outbreaks of the Black Death. The body horror in such imagery, reminiscent of something from a zombie movie, is hard to imagine today, especially in the developed world. To those who believed lust was a sin, the “pox” must have seemed like divine punishment, a foretaste of the tortures of the damned in a Hieronymus Bosch painting.

Like zombie horror today, a powerful undertone of class anxiety also played a role. 16 The association of frank sexuality with poverty, disease, and rotting flesh amplified Victorian sexual shame, turning pleasure into pathology. Perhaps, indeed, the sharp rise in horrific sexually transmitted infections associated with urbanization was the real driver of the sex-negativity that characterized the era’s pearl-clutching “purity literature.” 17

At any rate, female desire, whether feigned or real, was associated with the lower classes and their moral depravity, with animalistic “ungoverned lusts.” Bourgeois and upper-class women would ostensibly be far removed from all that, and if they weren’t, they would likely claim to be, the better to avoid social stigma, institutionalization, and perhaps even mutilation. Once again, Acton adds an eye-opening footnote to the passage quoted earlier, expanding on the correspondence of women’s sexuality with that of beasts:

*The physiologist will not be surprised that the human female should in these respects differ but little from the female among animals. We well know it, as a fact, that the dog or horse is not allowed approach to the female except at particular seasons. In the human female, indeed, I believe, it is rather from the wish of pleasing or gratifying the husband than from any strong sexual feeling, that cohabitation is habitually allowed. Certainly, it is so during the months of gestation. I have known instances where the female has during gestation evinced positive loathing for any marital familiarity whatever. In some of these instances, indeed, feeling has been sacrificed to duty, and the wife has endured, with all the self-martyrdom of womanhood, what was almost worse than death.

If respectable women can’t admit to sexual pleasure, greater female sexual flexibility is hard to distinguish from the expected—and required—“self-martyrdom of womanhood.” That would make it hard to tell the difference, from the outside, between a straight woman avoiding any great show of desire in her marriage for propriety’s sake, an asexual woman, and a woman who, whether straight or not, simply isn’t with a sexually compatible partner, and is thus “not very much troubled with sexual feeling of any kind.” 18

As one of the few female doctors seeing patients in the 19th century, Elizabeth Blackwell offered a different perspective:

The affectionate husbands of refined women often remark that their wives do not regard the […] sexual act with the same intoxicating physical enjoyment that they themselves feel, and they draw the conclusion that the wife possesses no sexual passion. A delicate wife will often confide to her medical adviser […] that […] when her husband’s welcome kisses and caresses seem to bring them into profound union, comes an act which mentally separates them, and which may be either indifferent or repugnant to her. But […] [it] is well known that terror or pain in either sex will temporarily destroy all physical pleasure. In married life, injury from childbirth, or brutal or awkward conjugal approaches, may cause unavoidable shrinking from sexual congress, often wrongly attributed to absence of sexual passion. […] It […] is also a well-established fact that in healthy loving women, uninjured by the too frequent lesions which result from childbirth, increasing physical satisfaction attaches to the ultimate physical expression of love. […] The prevalent fallacy that sexual passion is the almost exclusive attribute of men, and attached exclusively to the act of coition—a fallacy which exercises so disastrous an effect upon our social arrangements, arises from ignorance […]. A tortured girl, done to death by brutal soldiers, may possess a stronger power of human sexual passion than her destroyers. 19

As Blackwell hints when she writes of “increasing […] satisfaction,” figuring out what’s pleasurable, what works and what doesn’t, is an active process of exploration, learning, and even of self-creation—what Dan Savage has referred to as carving neural pathways. 20 In an environment where that kind of learning is discouraged, one’s own sexuality may remain undeveloped; sexual orientation itself may remain uncertain or undefined. This may account for a good deal of the asexuality reported by older women today.

To be fair, Victorian society also regarded “excessive” male sexuality as a problem. However, judgments in that quarter were more lenient, 21 and “treatments” were generally less grisly, though they did sometimes involve dubious tinctures, running current through electrodes inserted into the urethra, administering cold enemas, blistering the penis with harsh chemicals, and other activities not to everyone’s taste. 22

-Enhanced.webp)

In curbing excess male sexuality, the main goal was to avoid overtaxation, leading to (the theory went) a premature decline in virility, which would in turn compromise THE TRUE MISSION OF SEX. Remember that sex was, for husband and wife alike, a solemn duty, for race and country. As Lady Hillingdon allegedly wrote in her journal in 1912,

I am happy now that Charles calls on my bedchamber less frequently than of old. As it is, I now endure but two calls a week and when I hear his steps outside my door I lie down on my bed, close my eyes, open my legs and think of England. 23

For Acton, this was well and proper; “frigidity” in women wasn’t a problem. Male impotence was. Hence the passages from Acton’s book I’ve quoted at length are, counterintuitively, from a chapter on potential causes of male sexual dysfunction. Acton thought that fear of women’s sexual demands was a common cause of anxiety, impotence, and aversion to marriage among “nervous and feeble” young men—presumably both those who weren’t enthusiastic about marital rape, and those who were intimidated by the prospect of needing to satiate a “nymphomaniac” who did want sex.

In sum, fear and horror of female desire pervaded the culture on both sides of the Atlantic. The conjugal advice of Acton and his contemporaries seems perfectly calculated to make sex miserable—especially for women, but really, for everyone.

These attitudes have cast a long shadow. I remember, shortly after I moved to the US in the 1980s, being subjected to sex ed at school. Boys and girls were segregated, and the windows were blacked out with construction paper to prevent any salacious information leakage. Cryptic diagrams of internal organs and reproductive processes were projected onto the screen at the front of the classroom. Laughter was forbidden, on pain of being sent to sit out the rest of the period in the hall. The proceedings could not have been less appetizing, or more saturated with shame and dread. Many topics were covered, but most were medical and scary—fibroids, genital warts, teen pregnancy, AIDS, death.

In these classes, it went without saying that boys would try to talk girls into sex; also, that it was wrong, and that girls should listen to Nancy Reagan and “just say no.” As with drug use (also on the curriculum in that blacked-out room), the factors that might weaken a girl’s resolve and cause her to say “yes” were peer pressure or a self-sacrificing desire to please—never to be pleased. The idea of female sexual pleasure literally never came up. Nor is it mentioned in many sex ed programs today.

A 23-year-old woman from Galena, Ohio.

Robb, Strangers: Homosexual Love in the Nineteenth Century, 2004.

In case you’re dying to know whom Alfred had his love affair with: it was renowned Irish poet and playwright Oscar Wilde. The ensuing campaign of harassment and legal attacks instigated by Queensbury ultimately led to Wilde’s sentence—two years of imprisonment with hard labor—followed by self-exile and an untimely death in France.

Shifting usage and attitudes in the US have been influential globally, though it would be wrong to assume that the term has precisely equivalent meanings in other countries.

A somewhat antique-sounding phrase today, which I cribbed from the US Census to allow for apples-to-apples statistical comparison.

Bergler, Homosexuality: Disease or Way of Life?, 261–62, 1956.

This is part of the reason that in 2021, there were only 21 remaining lesbian bars in the United States, out of roughly 1,000 bars catering to gay men and LGBTQ+ people more generally. During the general downturn of the COVID pandemic, lesbian and Black-owned gay bars were hit hardest, due to the greater economic precarity of both their owners and their patrons. See “The 21 Bars —The Lesbian Bar Project”; Compton, “A Year into Pandemic, America’s Remaining Lesbian Bars Are Barely Hanging On,” 2021.

Nowadays it’s a common refrain that gay neighborhoods “aren’t what they once were.” Partly, as the stigma of being LGBTQ+ decreases (and more social life moves online), there’s less pressure on sexual minorities to move to such enclaves. Relatedly, it has become hard to counteract the dilution caused by an onslaught of straight people attracted to the vibrant nightlife in these neighborhoods.

A 67-year-old woman from Mishawaka, Indiana.

Stekel, Frigidity in Woman: In Relation to Her Love Life, 1926.

Acton, The Functions and Disorders of the Reproductive Organs, 144, 1867.

The full extent of the clitoris wasn’t well understood in the 19th century, but we can assume that Acton’s “excision of […] the whole” implied more extensive mutilation than removal of the glans.

Kellogg, Plain Facts for Old and Young, 1881; Graham, A Lecture to Young Men on Chastity: Intended Also for the Serious Consideration of Parents and Guardians, 1838; Kimmel, The History of Men: Essays on the History of American and British Masculinities, 50, 2005.

Acton, The Functions and Disorders of the Reproductive Organs, 144–45, 1867.

Acton, Prostitution, Considered in its Moral, Social, and Sanitary Aspects, in London and Other Large Cities: With Proposals for the Mitigation and Prevention of its Attendant Evils, 1857. These extremely high figures have been questioned by modern scholars, per Flanders, “80,000 Prostitutes? The Myth of Victorian London’s Love Affair with Vice.” Much of the debate turns on the precise definition of “prostitution,” which may have encompassed many sexual relationships out of wedlock—relationships that might not be recognized as sex work today, but that were similarly stigmatized at the time.

As sociology lecturer Phil Burton-Cartledge put it, “Zombies as a horror staple are the result of some unfathomable biological or supernatural crisis that cannot be reversed. They are mindless. They are faceless. They are ugly. And they want to invade your home and feast on your flesh. If this does not work as an allegory for bourgeois attitudes to and fears of the working class, I don’t know what does.” Burton-Cartledge, “Zombies and Ideology,” 2010.

As has often been remarked, pre-Victorian attitudes toward sex in “Merry Old England” (and elsewhere in the West) were far less repressive.

Of course, if you suspected your husband might be visiting sex workers, your desire for intimacy might also be tempered by fear of contracting the pox.

Blackwell, Essays in Medical Sociology, 52–54, 1902.

Savage, “Savage Love: Fresh Starts,” 2018.

For example, while US Surgeon General William Hammond wrote in Sexual Impotence in the Male, “That the civilized man is in general excessive in the matter of sexual intercourse admits of no question,” he then hedges vaguely: “The question then arises, what is excess? There are men who think it entirely within bounds to have sexual intercourse once every twenty-four hours; others, again, indulge regularly twice a week; others once; still, others who think once a month sufficient. It is exceedingly difficult to lay down any rule in the matter which will be applicable to all men […].” Sexual Impotence in the Male, 128–29, 1883.

Though it didn’t extend to penectomy or castration, boys weren’t spared Kellogg’s sadism; he advocated circumcision, without anesthetic, for those who couldn’t be “cured” of masturbation by less drastic means. Kellogg, Plain Facts for Old and Young, 1881.

This oft-cited diary entry may well be apocryphal; see Tréguer, “History of the Phrase ‘Close Your Eyes and Think of England,’” 2019.