Priests, moralizers, politicians, lawyers, and policemen have been branding non-heterosexual orientation and behavior as pathological for thousands of years—but nobody out-pathologizes doctors. A number of strong opinions by MDs in this vein have already come up; in order of appearance so far: Cesare Lombroso, Wilhelm Stekel, Sigmund Freud, Wilhelm Fliess, Michael Ryan, Thomas Nichols—a frock-coated and bewhiskered panel of learned men. It’s easy to understand why doctors have assumed this role. They traditionally consider the body in terms of organs and systems with well-defined functions, and it’s their job to diagnose and, when possible, address dysfunctions.

Elizabeth Blackwell (1821–1910), the first woman to receive a medical degree in the United States, offered a humbler take on our understanding of function in the human body in her 1894 book The Human Element in Sex:

The Christian physiologist […], knowing that there is a wise and beneficent purpose in the human structure, seeks to find out the laws and methods of action by means of which human function may accomplish its highest use. This task can only be carried out gradually. Ultimate function is not revealed by structure, nor ultimate use by function. […] Ignorance of facts, preconceived notions, or fanciful theories as to “vital spirits,” “cold and hot humours,” &c., long delayed the attainment of correct knowledge of physiological facts. Neither does physical knowledge of individual function reveal the developed use of which it is capable. […] Function and use are only proved by observation, reflection, and rational experiment patiently carried on age after age, with generalisation based upon accurate and accumulated facts. 1

Where Blackwell’s Christianity led her to advocate caution in presuming to understand the ultimate functions of human bodies, most of her (male) contemporaries drew the opposite conclusion—also on religious grounds. For them, the detailed workings of, say, the uterus might remain mysterious, but its purpose is spelled out clearly enough in the Bible: to “be fruitful, and multiply.” 2 Unfortunately, Blackwell’s views were—and remain—in the medical minority.

Philosophers refer to the idea that everything is for something as teleology. Why should a doctor not apply this idea to sex? It’s a seemingly powerful yet circular argument: if a body part cannot fulfill its natural function, then you have a physical disorder. If it can do so but you are not using it to fulfill its natural function, then you’re mentally disordered, committing a crime against nature. You’re doing it wrong. And there will be consequences, since our health as individuals and as a species depends on these natural functions. As the phrenologist Samuel Roberts Wells (1820–1875) put it when dispensing “scientific” marriage advice,

[W]hen art and nature are thrown into positions of antagonism, as they often are under the present order of things, deterioration and decadence are the results. Man has dominion over nature. The unphysiological habits and pernicious systems of education so prevalent at the present day, especially in cities, tend to produce precocity and a depreciation of vital stamina. The natural order of development is often subverted […]. 3

So, it falls to medical professionals to tell us what is natural and what is pathological or “unphysiological.” By drawing this distinction, they tell us both who we are and who we are not—that is, who falls outside the boundaries of the acceptable.

While medicine is an ancient field with roots in traditional practices dating back to Ice Ages, we should keep in mind that beyond herb-lore, lancing boils, and the like, it’s only over the last two centuries that surgery and “physic” have merged into an organized profession endowed with the skill and knowledge to reliably cure disease, 4 rather than philosophizing and conducting magic rituals, whether shamanic (like dancing) or pseudo-scientific (like bloodletting).

As medicine has become more effective, physicians have gained moral authority, arguably surpassing that of the church, especially when we consider how universally their judgment is trusted, and how consequential that judgment can be. Doctors wield scalpels, administer treatments, and prescribe drugs, both with and without patients’ consent—for consent is not the norm when those patients are minors, or when they’re deemed incompetent. 5 Doctors can also determine people’s legal status as competent or incompetent, normal or deranged, safe to be in public or condemned to an institution… where their consent also ceases to matter. With or without ill intent, this power has often been abused. The next several chapters will feature some vivid examples, continuing up to the present day.

Lavinia Dock (1858–1956), a feminist pioneer in nursing education, characterized this frequent overreach in her notes on a 1902 conference in Brussels on the regulation of prostitution. Like Blackwell, Dock critiqued a patriarchal medical establishment that was not only ignorant outside a narrow purview, but blind to its own ignorance:

This […] conference [was] very remarkable not only for the facts brought out, but also as showing, along with the rapidly advancing tendency of the best medical thought to think in unison with social moralists […] two things especially: one, the immense handicap of involuntary, unconscious sex dominance and egotism to men discussing these problems: the other, the conspicuous ignorance of many great medical specialists in matters of sociology. It is a mistake to suppose that an eminent authority in one line will be equally eminent as an authority in another. As a matter of fact, the general esteem and confidence proffered to the medical profession by the public has sometimes encouraged its members to believe that their pronouncements on social conditions are as final as their definitions of medical knowledge. 6

To see the trick in action—medical knowledge morphing into teleology, and then into moral judgment, and then into social prescription—consider Henry Stanton’s 1922 book Sex: Avoided Subjects Discussed in Plain English, 7 a typical and popular pamphlet of its era designed to help parents instruct their children in the “facts of life”:

As we mount the ascending ladder of plant and animal life the unit-cell of the lower organisms is replaced by a great number of individual cells, which have grown together to form a completed whole. […] Philosophically it may be said that [the egg and sperm] cells directly continue the life of the parents, so that death in reality only destroys a part of the individual. Every individual lives again in his offspring. 8

So far, so good. There is something beautiful and true in this grand picture, a hint of the way our individual bodies aren’t so individual, but are connected through the generations, as with a spacetime spiderweb, by the tiny strands of our germline. A chicken is just an egg’s way of making another egg, as the old saying goes.

But, like any description, this isn’t a view from nowhere. It again evokes the Great Chain of Being familiar to the theologians and natural philosophers of previous centuries, in which complex multicellular animals like us are at the top of the hierarchy of living things on Earth. It also prescribes the role, or natural function, of egg and sperm cells.

Now comes the rub. For them to fulfill this natural function, the organism as a whole has to do its bit. So, Stanton gets down to business:

THE TRUE MISSION OF SEX

This rebirth of the individual in his descendants represents the true mission of sex where the human being is concerned. And reproduction, the perpetuation of the species, underlies all rightful and normal sex functions and activities. 9

This short passage, neatly harmonizing religious, scientific, and medical doctrines, encapsulates historical attitudes to lesbian, gay, and trans people: they’re unnatural and disordered because their sex lives aren’t furthering the reproductive mission.

Nationalism, racism, and classism play a part here too. Sexual reproduction, says Stanton, “underlies the vigor and racial power of every nation.” 10 Hence shirking one’s reproductive duty has overtones not only of self indulgence, but of betraying race and country. At the time, anxieties were running high about the sexually restrained bourgeoisie being out-reproduced by foreigners and poor people—and indeed, the correlation between poverty and high birth rate is real, as Part III of this book will explore. Conversely, the trend toward sharply lower birth rates described in the previous chapter holds not only in the US, but in all economically developed countries. This correlation was already apparent to scholars by the end of the 18th century, and had become something of a demographic panic by the early 20th.

Stanton’s widely held perspective carries many other implications, too. For one, the enjoyment of sex should be secondary to thinking of it as a duty. Thus, birth control (at least, by the wealthy) is monstrous, as is, obviously, any kind of sex that can’t result in conception, such as oral or anal sex, or even masturbation (hence the old time euphemism for it, “self abuse”). Thus the original meaning of sexual “deviancy” or “perversion”: any activity that perverts or deviates from the “naturally” reproductive function of sex.

The most widely read work on “sexual deviancy” of its generation was pioneering sexologist Richard von Krafft-Ebing’s 1886 book Psychopathia sexualis. 11 Profoundly influenced by Lombroso, 12 it’s full of lurid “medico-legal” case studies, peppered with Latin to project a scholarly veneer (and maybe to keep its titillations out of reach of women, children, and the vulgar masses). Krafft-Ebing introduced English readers to many new terms, including “heterosexuality,” “homosexuality,” “bisexuality,” “sadism,” and “masochism.”

Like Lombroso, he considered homosexuality, in particular, “a functional sign of degeneration, and […] a partial manifestation of a neuro-psychopathic state, in most cases hereditary.” 13 In other words, just as “criminality” was deemed evidence of being degenerate or primitive, so was being lesbian, gay, trans, or anything else Krafft-Ebing regarded as “deviant”; all were steps down the Chain of Being, and into the non-reproductive gutters of society.

The consequences were severe. Given the draconian sodomy laws in force at the time, LGBT people were legally criminals—a textbook instance of circular reasoning.

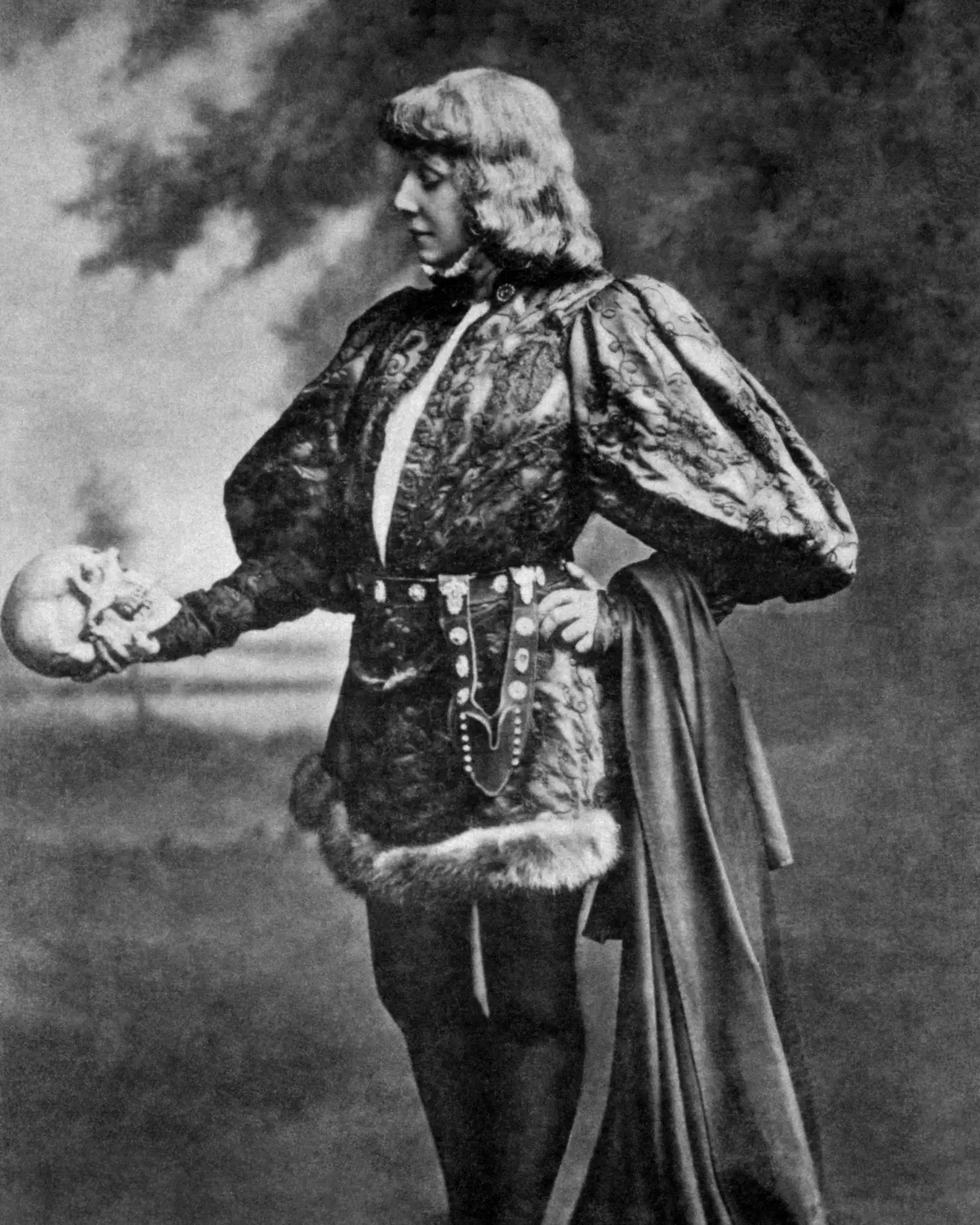

Many case studies in Psychopathia sexualis vividly illustrate these points. They also make for heartbreaking reading today. Case 131, for example, is the story of “Count Sandor V,” who was arrested in 1889, 14 and discovered to be “no man at all, but a woman in male attire”:

Among many foolish things that her father encouraged in her was the fact that he brought her up as a boy, called her Sandor, allowed her to ride, drive, and hunt, admiring her muscular energy. […] At thirteen she had a love-relation with an English girl, to whom she represented herself as a boy, and ran away with her. […] She recognized the abnormality of her sexual inclinations, but had no desire to have them changed, since in this perverse feeling she felt both well and happy. 15

After a youth in which Count S. “became independent, and visited cafés, even those of doubtful character,” “was a very skillful fencer,” “carried on literary work, and was a valued collaborator on two noted journals,” she found:

A new love […] Marie, and her love was returned. Her mother and cousin tried in vain to break up this affair. […] In April, 1888, Count S. paid her a visit, and in May, 1889, attained her wish; in that Marie—who, in the meantime, had given up a position as teacher—became her bride in the presence of a friend of her lover, the ceremony being performed in an arbor, by a false priest, in Hungary. S., with her friend, forged the marriage-certificate. The pair lived happily, and, without the interference of the step-father, this false marriage, probably, would have lasted much longer. 16

If only this passage had ended with the sentence “The pair lived happily ever after,” we’d have a sweet, gender-expansive love story; then again, if the couple had remained undiscovered (as must have happened in some cases) we also wouldn’t have a medico-legal record.

We don’t know what became of Marie, but we do know that upon being outed, Count S. fell victim to the legal, psychiatric, and medical institutions of the day, and was imprisoned.

The first meeting which the experts had with S. was, in a measure, a time of embarrassment to both sides; for them, because perhaps S.’s somewhat dazzling and forced masculine carriage impressed them; for her, because she thought she was to be marked with the stigma of moral insanity.

The ordeal must have been both terrifying and humiliating. A lengthy, chillingly invasive examination ensues, much abbreviated here:

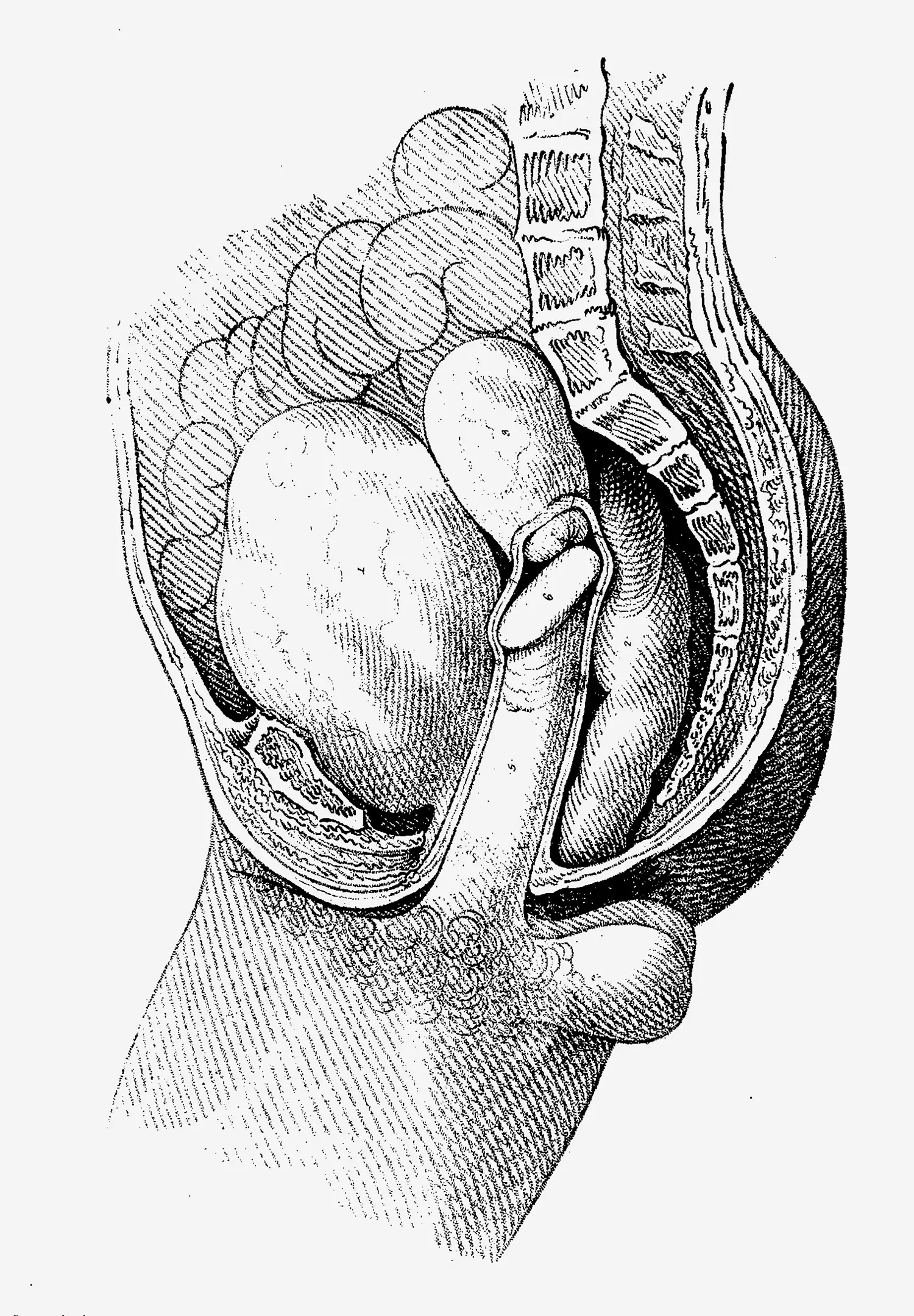

She is 153 centimetres tall, of delicate skeleton, thin, but remarkably muscular on the breast and thighs. Her gait in female attire is awkward. Her movements are powerful, not unpleasing, though they are somewhat masculine, and lacking in grace. […] Feet and hands remarkably small, having remained in an infantile stage of development. […] The skull is slightly oxycephalic, and in all its measurements falls below the average of the female skull by at least one centimetre. […] The circumference of the head is 52 centimetres; the occipital half-circumference, 24 centimetres; the line from ear to ear, over the vertex, 23 centimetres; the anterior half-circumference, 28.5 centimetres; the line from glabella to occiput, 30 centimetres; the ear-chin line, 26.5 centimetres; long diameter, 17 centimetres; greatest lateral diameter, 13 centimetres; diameter at auditory meati, 12 centimetres; zygomatic diameter, 11.2 centimetres. […] Genitals completely feminine, without trace of hermaphroditic appearance, but at the stage of development of those of a ten-year-old girl. […] The pelvis appears generally narrowed (dwarf-pelvis), and of decidedly masculine type. […] On account of narrowness of the pelvis, the direction of the thighs is not convergent, as in a woman, but straight.

The opinion given showed that in S. there was a congenitally abnormal inversion of the sexual instinct, which, indeed, expressed itself, anthropologically, in anomalies of development of the body, depending upon great hereditary taint; further, that the criminal acts of S. had their foundation in her abnormal and irresistible sexuality. 17

Count S. was lucky—and doubtless benefited from high socioeconomic class, a university education, literary talent, and eloquence:

“Gentlemen, you learned in the law, psychologists and pathologists, do me justice! Love led me to take the step I took; all my deeds were conditioned by it. God put it in my heart.

“If He created me so, and not otherwise, am I then guilty; or is it the eternal, incomprehensible way of fate? I relied on God, that one day my emancipation would come; for my thought was only love itself, which is the foundation, the guiding principle, of His teaching and His kingdom.”

[…] The court granted pardon. The “countess in male attire,” as she was called in the newspapers, returned to her home, and again gave herself out as Count Sandor. Her only distress is her lost happiness with her beloved Marie.

Carousing, love affairs, duels, and financial troubles aside, Sándor Vay went on to become a prolific and successful writer, ultimately collecting 400 stories and publishing them in 15 volumes. In 1908, two years before his death, a street in his native town of Gyón was named Count Sándor Vay in his honor.

Many of the subjects of Krafft-Ebing’s case studies weren’t so fortunate; their stories often ended in suicide or internment in an asylum for life.

Remarkably little seemed to have changed by the time the American Psychiatric Association published the first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1952. It, too, defined “sexual deviation” as a form of criminal pathological behavior—not drawing distinctions based on harm or violation of consent, but on violation of social norms:

The term includes most of the cases formerly classed as “psychopathic personality with pathologic sexuality.” The diagnosis will specify the type of the pathologic behavior, such as homosexuality, transvestism, pedophilia, fetishism and sexual sadism (including rape, sexual assault, mutilation). 18

The DSM’s characterization of homosexuality as a mental illness reflected the views of the foremost psychoanalytic theorist of homosexuality in the 1940s and ’50s, Dr. Edmund Bergler. He coined the term “writer’s block” in 1947, and wrote books on gambling, self-harm, midlife crises, and (albeit rather humorlessly) the basis of humor. He was also a strong proponent of conversion therapy—and for a psychiatrist to offer such a service, there needed to be a diagnosis. The DSM delivered exactly that.

Bergler’s popular 1956 paperback, Homosexuality: Disease or way of life? answers the titular question right on the cover, with an inset reading, “A world-famous psychoanalyst’s inquiry into the causes of homosexuality and the possibilities for its cure.” In the opening chapter, What is a homosexual?, he writes,

For nearly thirty years now I have been treating homosexuals, spending many hours with them in the course of their analyses. I can say with some justification that I have no bias against homosexuals; for me they are sick people requiring medical help. […] Still, though I have no bias, if I were asked what kind of person the homosexual is, I would say: “Homosexuals are essentially disagreeable people, regardless of their pleasant or unpleasant outward manner. True, they are not responsible for their unconscious conflicts. However, these conflicts sap so much of their inner energy that the shell is a mixture of superciliousness, fake aggression, and whimpering. Like all psychic masochists, they are subservient when confronted with a stronger person, merciless when in power, unscrupulous about trampling on a weaker person […] you seldom find an intact ego (what is popularly called ‘a correct person’) among them.” 19

This passage reveals the way moral judgment can be inflicted while gaslighting: Bergler is “unbiased,” because he’s writing dispassionately and authoritatively, as a celebrated doctor and researcher. Any critical response to his judgment, in particular from a gay person, would doubtless be interpreted as evidence of just the kind of “denial,” “aggression,” and “neurosis” that he claims characterize gayness.

Perhaps most gallingly, Bergler’s brisk business in conversion therapy (by 1959 he claimed to have “treated” over a thousand gay patients 20 ) both preyed on and amplified his victims’ internalized homophobia:

Newer psychiatric experiences and studies have proved conclusively that the allegedly unchangeable destiny of homosexuals (sometimes even ascribed to nonexistent biological and hormonal conditions) is in fact a therapeutically changeable subdivision of neurosis […] today, psychiatric-psychoanalytic treatment can cure homosexuality.

The homosexual of either sex believes that his only trouble stems from the “unreasonable attitude” of the environment. If he were left to his own devices, he claims, and no longer needed to fear the law or to dread social ostracism, extortion, exposure (all leading to constant secrecy and concealment), he could be just as “happy” as his opposite number, the heterosexual. This, of course, is a self-consoling illusion. Homosexuality is not the “way of life” these sick people gratuitously assume it to be, but a neurotic distortion of the total personality […] there are no healthy homosexuals. 21

.webp)

From a 21st century perspective, the cartoonish awfulness of these passages might tempt one to believe that Bergler’s views were unusually bigoted; however, this isn’t the case. While nascent gay rights publications critiqued the book, it was squarely within the medical, psychiatric, and popular mainstream of the 1950s. Time magazine, for instance, reviewed his work positively on its publication in 1956 and again in 1959, concluding,

Dr. Bergler holds that every homosexual can be cured in about eight months of psychiatric treatment. All he needs is the will to change, and the willingness to accept that what he really seeks is not synthetic sex but self-punishment. But if he wants to persist in self-punishment, homosexuality is certainly the most efficient means to that unhappy end. 22

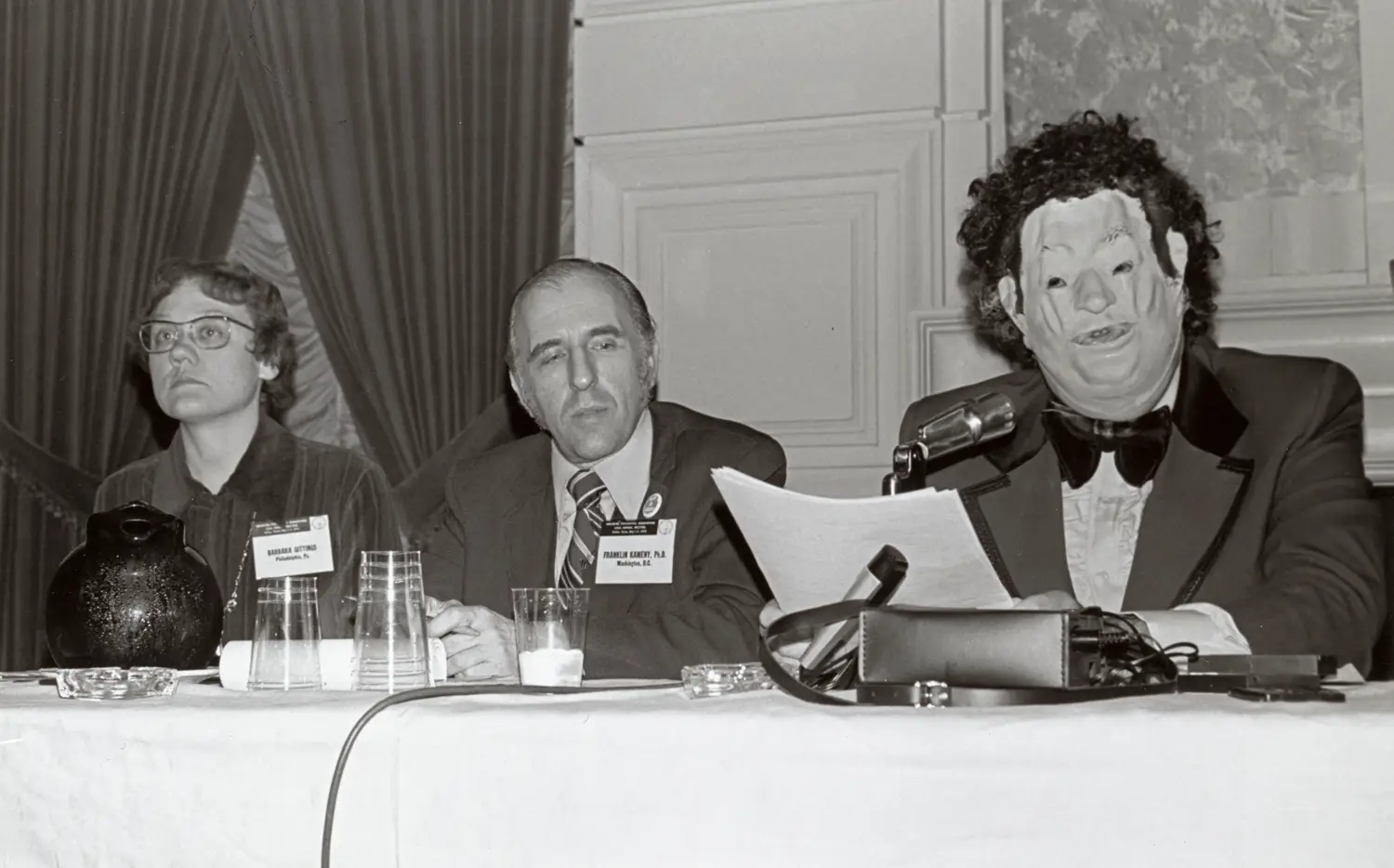

The DSM-II, published in 1968, made no significant change, but amid mounting pressure from gay rights groups to de-pathologize homosexuality, the APA issued a rather tortured revision memo in 1973. The memo tried to split the difference, keeping “Sexual orientation disturbance (Homosexuality)” (emphasis mine) listed as a disorder:

This category is for individuals whose sexual interests are directed primarily toward people of the same sex and who are either disturbed by, in conflict with, or wish to change their sexual orientation. This diagnostic category is distinguished from homosexuality, which by itself does not constitute a psychiatric disorder. 23

The absurdity soon devolved into ridiculousness and internal contradiction. In justifying the change, the memo acknowledged that not all gay people think of themselves as mentally ill, and allowed that this might be true, though in the process it still managed to condemn homosexuality as a “failure to function optimally”—for good measure, throwing celibacy, revolutionary behavior, male chauvinism, and vegetarianism under the same bus. 24

Clearly homosexuality, per se, does not meet the requirements for a psychiatric disorder since […] many homosexuals are quite satisfied with their sexual orientation and demonstrate no generalized impairment in social effectiveness or functioning. The only way that homosexuality could therefore be considered a psychiatric disorder would be the criteria of failure to function heterosexually, which is considered optimal in our society and by many members of our profession. However, if failure to function optimally in some important area of life as judged by either society or the profession is sufficient to indicate the presence of a psychiatric disorder, then we will have to add to our nomenclature the following conditions: celibacy (failure to function optimally sexually), revolutionary behavior (irrational defiance of social norms), religious fanaticism (dogmatic and rigid adherence to religious doctrine), racism (irrational hatred of certain groups), vegetarianism (unnatural avoidance of carnivorous behavior), and male chauvinism (irrational belief in the inferiority of women). 25 […]

[By] no longer listing [homosexuality] as a psychiatric disorder we are not saying that it is “normal” or as valuable as heterosexuality. […]

What will be the effect of carrying out such a proposal? No doubt, homosexual activist groups will claim that psychiatry has at last recognized that homosexuality is as “normal” as heterosexuality. They will be wrong. 26

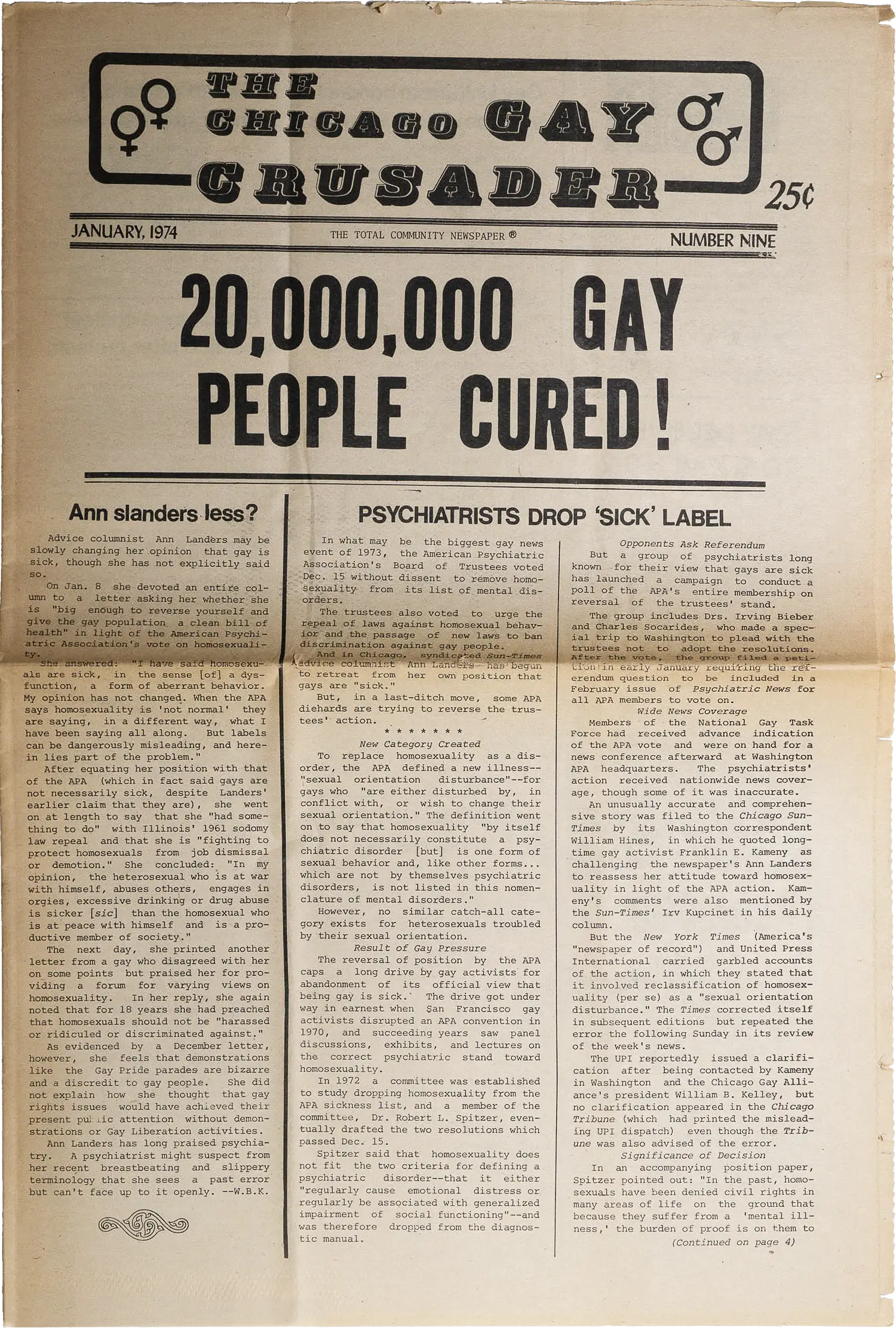

The 1973 DSM revision is celebrated to this day as an important milestone in gay rights, when millions of Americans were suddenly “cured,” per a snarky headline in the Chicago Gay Crusader. By maintaining that homosexuality was abnormal and less “valuable” than heterosexuality, though—and by keeping a diagnosis on the books for gay people who were dissatisfied with their “failure to function optimally”—the Dr. Berglers of the world got to keep plying their trade.

The idea that homosexuality or bisexuality were disorders at all was finally dropped with the publication of the DSM-III-R in 1987. So, when I was being taught sex ed at school in a suburb of Baltimore in 1986, “sexual orientation disturbance (homosexuality)” was still “officially” a mental disorder in the US. It’s unsurprising, then, that a 35-year-old man from Nashville, Tennessee, would write in the survey, unprompted, “tranny and gay are forms of mental illness most likely stemming from childhood abuse (possibly sexual).” Mainstream psychiatrists within living memory had no compunctions about expressing similar views.

Some key aspects of our sexual identity and orientation (including how flexible these are) seem to be wired into our developing brains even before we’re born, as the next several chapters will show—though the underlying mechanisms are still poorly understood. 27 That’s probably why “gay conversion” has so consistently failed, despite decades of attempts.

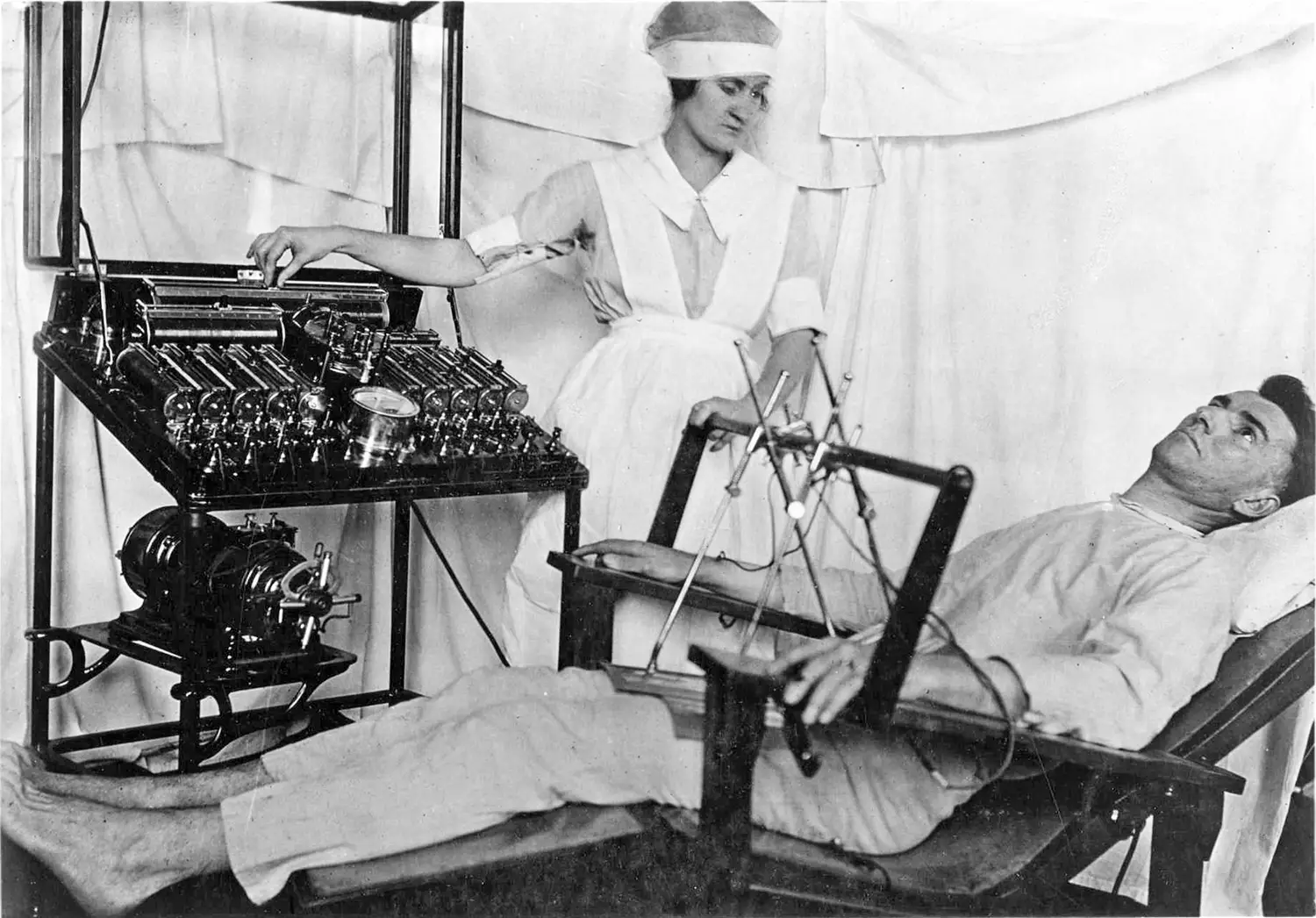

Conversion attempts haven’t been limited to talk therapy. They have included hypnosis and aversion therapy—exposure to physical discomfort, pain, or traumatic stimuli. Of course if the intervention is blunt and drastic enough, sexuality, and other aspects of the self, can be damaged or broken. Castration 28 and so-called “chemical castration” have been used. Lobotomy was used frequently, as were electroshock treatments; a 1935 presentation to the APA noted that converting homosexuals required electroshock intensities “considerably higher than those usually employed on human subjects.” 29

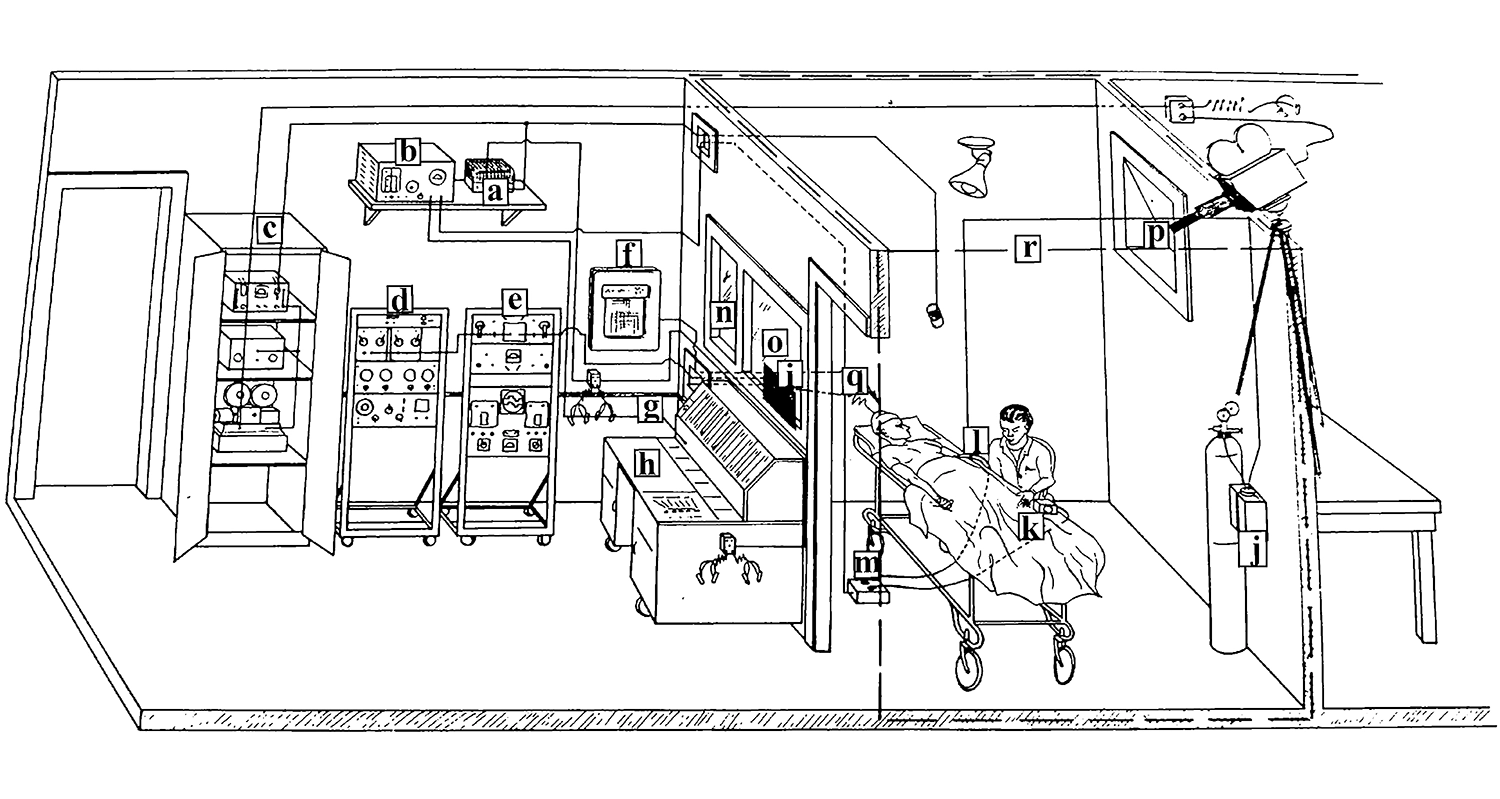

In a particularly bizarre 1972 experiment by Robert Heath, the founder of Tulane University’s Department of Psychiatry and Neurology, a gay 24-year-old who had been institutionalized for suicidal depression had electrodes implanted deep into his brain. These were stimulated, first prior to masturbating to heterosexual porn, then just before being coaxed into having sex with a female sex worker whom Heath had hired for the purpose and brought into the lab. According to one of the papers in which Heath published this “research” (amidst impressive but incomprehensible graphs of recorded brain activity before, during, and after orgasm), “the patient began active participation and achieved successful penetration, which culminated in a highly satisfactory orgastic response, despite the milieu and the encumbrances of the lead wires to the electrodes.” 30 Yikes!

Importantly, Robert Heath, like Edmund Bergler, was not a fringe figure, nor was this, at the time, generally regarded as fringe science. Heath wrote 420 articles and 3 books, collaborated extensively, and chaired his department until his retirement in 1980, concluding a long research career. In 1985 Tulane awarded him an honorary doctorate and created an endowed lectureship and professorship in his honor.

As of this writing, the rather dusty website of The Robert Heath Society, the alumni association of the Tulane University School of Medicine Department of Psychiatry and Neurology, is still online. 31 In the Society’s Spring 2005 newsletter, a “Historical Perspective” is offered under the heading “Robert G. Heath: ‘A Perfect Gentleman.’” It begins, “Confucius said that the three virtues of a ‘perfect gentleman’ were wisdom, courage, and benevolence,” and goes on to make the case for these qualities. His colleagues, it seems, remember him fondly.

Modern human subject research protocols forbid such gruesome experiments, and as described in Chapter 2, the most prominent contemporary gay conversion programs have all imploded. However, we are still arguing about what is “natural” and what is not.

It’s tempting to dismiss the entire teleological premise by affirming our humanism, our agency to do with our bodies anything we want, and “nature” be damned. We’re not just animals! Our internal organs might perform their monotonous yet essential life-support functions, whether we will them to or not, but when it comes to behaviors we can consciously control, freedom and the human spirit prevail. In this view, our sex organs are “for” procreative sex no more or less than our hands are “for” picking fruit, squishing lice, or whatever else our ancestors did with them millions of years ago. Not everything has to have a “for” anymore. Evolution may have given us our bodies, but we’re human precisely because we can do with them as we please. We get to choose our own lifestyle.

In its pure form, this argument isn’t much more defensible than Stanton’s moralizing, though. For one, the idea that we humans are so different from the rest of nature is dubious. If we have agency, so too, surely, do our close cousins the bonobos (or “pygmy chimpanzees,” as they were once called), and they have lots of non-procreative sex, as well as engaging in frequent play and other human-like activities. Homosexual behavior, too, is commonplace in other species. 32 Yet when we see nonhuman animals participating in such activities, we’re unsatisfied with the individualistic justifications we reserve for ourselves—choice and pleasure—instead reaching for collective, functional explanations such as “troop bonding and cohesion,” presuming that these are instinctive behaviors that must serve some larger evolutionary purpose. Indeed, when we look closely enough, we can often find one.

So do we choose how to behave, or is it chosen for us by our essential nature? Seemingly, we want to have it both ways. Modern liberal values are predicated on safeguarding our freedom to choose how to live. On the other hand, the lesbian, gay, and trans rights movements have at times been at pains to point out how little choice we have in our gender or sexual orientation—hence the failures of conversion therapy. How much sexual choice and freedom we each really have is a profound question with real-life implications. The survey data can offer some insight here.

Blackwell, The Human Element in Sex: Being a Medical Inquiry into the Relation of Sexual Physiology to Christian Morality, 1–2, 1894.

Gen. 1:28 (KJV).

Wells, Wedlock; Or, the Right Relations of the Sexes: Disclosing the Laws of Conjugal Selection, and Showing Who May, and Who May Not Marry, 22, 1884.

Schneider, The Invention of Surgery, 2021.

Or, worse, undesirable, like the Jewish women in Linz in 1938, wearing placards in the public square announcing that they had been “excluded from the national community” (see Chapter 3). In the United States, such “undesirability” has motivated forced sterilization campaigns for Black, Native, and Latin American men and women.

Dock, Hygiene and Morality: A Manual for Nurses and Others, Giving an Outline of the Medical, Social, and Legal Aspects of the Venereal Diseases, 84–85, 1910.

Stanton, Sex: Avoided Subjects Discussed in Plain English, 1922. Many, many other 19th and 20th century books could illustrate the point equally well.

Stanton, 8–9.

Stanton, 9.

Stanton, 50.

Quotes are from Krafft-Ebing, Psychopathia Sexualis with Especial Reference to Contrary Sexual Instinct: A Medico-Legal Study; Authorized Translation of the Seventh Enlarged and Revised German Edition, 1893.

Psychopathia sexualis cites Lombroso’s work 25 times.

Krafft-Ebing, Psychopathia Sexualis, 225, 1893.

See also Mak, “Sandor/Sarolta Vay: From Passing Woman to Sexual Invert,” 2004.

Krafft-Ebing, Psychopathia Sexualis, 311, 1893.

Krafft-Ebing, 312.

Krafft-Ebing, 316–17.

American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual: Mental Disorders (DSM-I), 39, 1952.

Bergler, Homosexuality: Disease or Way of Life?, 26, 1956.

Bergler, One Thousand Homosexuals: Conspiracy of Silence, or Curing and Deglamorizing Homosexuals?, 1959.

Bergler, Homosexuality: Disease or Way of Life?, 9, 1956. Emphasis is in the original; Bergler was fond of italics.

“Medicine: The Strange World,” 1959.

American Psychiatric Association, “Homosexuality and Sexual Orientation Disturbance: Proposed Change in DSM-II, 6th Printing, Page 44, Position Statement (retired),” 1973.

Of course, like any organization with more than a handful of people, the APA had many members who were themselves gay; they were almost without exception deeply closeted at the time. A 1998 article in the New York Times, for instance, details the coming-out of a prominent psychoanalyst, Dr. Ralph Roughton, former director of the Emory University Psychoanalytic Institute. It was not until 1996 that “he looked around at his profession and recognized that the need for secrecy, for pretending to be someone that he was not, was no longer so urgent.” Goode, “On Gay Issue, Psychoanalysis Treats Itself,” 1998.

None of the six officers of the APA were women, but perhaps Henriette R. Klein contributed this item, as the only woman among the 14 trustees and 17 ex-officio non-voting members of the board?

American Psychiatric Association, “Homosexuality and Sexual Orientation Disturbance: Proposed Change in DSM-II, 6th Printing, Page 44, Position Statement (retired),” 1973.

Mbũgua, “Reasons to Suggest that the Endocrine Research on Sexual Preference Is a Degenerating Research Program,” 2006.

Guy T. Olmstead underwent voluntary castration in 1894 to “overcome” his homosexuality, per Katz, Gay American History: Lesbians and Gay Men in the U.S.A.; A Documentary, 1976.

Katz, 252.

Heath, “Pleasure and Brain Activity in Man: Deep and Surface Electroencephalograms During Orgasm,” 1972.

“Robert Heath Society,” 2013, link.

Bagemihl, Biological Exuberance: Animal Homosexuality and Natural Diversity, 2000.