Does the idea of an “official definition” of ambidexterity even make sense? Official, says who? Ambidexterity isn’t a mathematical concept; it doesn’t refer to something that has an objective meaning independent of our language and culture.

In fact, the term “ambidextrous” is used in various communities—not just medicine, but also sports and music, for example—and in each it means something a bit different, sometimes rare, sometimes commonplace. If we think that one of these communities holds a copyright on what ambidexterity means, then we’d be creating a hierarchy of authority to police the term. If we went with the medically sanctioned “1%” definition, then we’d be claiming that 90% of those who say they’re ambidextrous are just confused—not a case I’d be keen to make. Instead, I’ll focus on being descriptive, not prescriptive—a stance I’ll try to maintain throughout the book.

I’m aware that this argument skirts difficult territory. We’re living through a period of “alternative facts,” conspiracy theories, and the devaluation of science by large segments of the population. I stand firmly with science—paying close attention to data when exploring fuzzy, socially defined concepts, rather than relying on orthodoxy or arguments from authority.

It has long been known that handedness is a fuzzy concept. Noticing the wide range of left-handedness estimates at the time, Hardyck and Petrinovich wrote that handedness “is most appropriately regarded as a continuum”—what we might today call a “spectrum.” In the survey data, there aren’t any continuous measures, like grip strength or hand size, but quite a few yes/no questions about handedness allow one to render a continuous “halftone” picture of it:

Do you have a right hand?

Do you have a left hand?

Is your right hand bigger than your left?

Is your left hand bigger than your right?

Do you write with your right hand?

Do you write with your left hand?

Can you write equally well with your left and right hands?

When you use a computer mouse or trackpad, do you tend to use your right hand?

When you use a computer mouse or trackpad, do you tend to use your left hand?

When you cross your arms, is your right forearm on top?

When you cross your arms, is your left forearm on top?

When you clasp your hands, is your right thumb on top?

When you clasp your hands, is your left thumb on top?

When you wink, does your right eye close?

When you wink, does your left eye close?

When you type, do you usually use the right shift key?

When you type, do you usually use the left shift key?

Do you normally hold scissors in your right hand?

Do you normally hold scissors in your left hand?

Was your mother right-handed?

Was your mother left-handed?

Was your father right-handed?

Was your father left-handed?

Did you have trouble with handwriting as a child?

Were you made to change your dominant hand as a child?

Do you work in tech?

Do you work in the arts?

Are you a strong verbal communicator?

Do you play a musical instrument?

Are you good at drawing?

All of these are potential “handedness correlates.” Some of the questions seem like they should correlate strongly—such as whether you write with your left hand—while others are speculative and based on possibly bogus theories—such as whether you’re good at drawing or play an instrument. 1 Is it really true that artists tend to be left-handed? Let’s find out!

Imagine making a composite left-handedness “score” for a given respondent by counting the “yes” answers that seem to support left-handedness (“Is your left hand bigger than your right?” “Do you write with your left hand?” and so on). Perhaps this score could be improved by subtracting the number of “yes” answers that argue against left-handedness (“Is your right hand bigger than your left?” “Do you write with your right hand?”). Each question, then, would contribute a +1 or −1 to an overall left-handedness score. Let’s call the +1 or −1 number for each question its “weight” for calculating that score.

This procedure might give a reasonable first approximation of a “left-handedness spectrum,” but it has some obvious drawbacks. Some questions, like “Do you work in tech?” might be correlated with handedness, but it would be dangerous to assume so. It might be safest simply not to count them after all; put differently, maybe their real weight should be zero.

Then, too, it seems obvious that certain questions, like “Do you write with your left hand?” ought to count for a lot more than “Was your mother left-handed?” So, ideally, questions should have a range of different weights, not just the +1, 0, and −1 weights of the simpler “bookkeeping” approach. But now we’re in trouble. How can one guess what those weights should be?

Luckily, no guessing is required. Instead, canny data scientists can use a mathematical technique called “optimal linear estimation,” which allows the weights to be calculated directly from the data. It requires a cheat sheet, which in this case, the survey itself supplies: weights combine with the answers to questions like “Do you write with your left hand?” and “Was your mother left-handed?” to predict the answers to handedness questions. An “optimal” set of weights for right-handedness aims to produce a positive score for everyone who answered “yes” to “Are you right-handed?” and a negative score for everyone who answered “no.” The optimal weights for left-handedness, conversely, aim to produce a positive score for everyone who answered “yes” to “Are you left-handed?” and a negative score for everyone who answered “no.”

Branches of applied math are dedicated to solving “optimization problems” like these. A fancier version, “nonlinear optimization,” is the foundation of most modern AI, so very much part of my day job. Linear optimization is more straightforward, though. My laptop spit out optimal weights in about a millisecond, sorted from most positive (shown here as the longest bar extending to the right) to most negative (the longest bar extending to the left). 2 Unsurprisingly—though it did not have to work out this way—the strict right-handedness and strict left-handedness weights are nearly perfect mirror images of each other.

There are no big surprises in the weights themselves either. The hand you write with, and the hand you hold scissors with, make the strongest contributions to predicting strict left-handedness, both positive (“Do you write with your left hand?”) and negative (“Do you write with your right hand?”). The opposite holds for strict right-handedness. Parental influence is a factor too, though it’s much weaker, with mom’s handedness playing a stronger role than dad’s. 3 Questions about drawing, music, working in tech, and being a strong verbal communicator are so close to zero as to be uninformative—those theories indeed look bogus.

With this ability to calculate a strict left-handedness score, a nuanced, “halftoned” rendition of strict left-handedness emerges, as promised. In practice, this looks like a histogram of left-handedness scores, with error bars as usual. For each bin, it shows, in different colors, the percentage of respondents who report being strictly left-handed, strictly right-handed, or whose responses are ambiguous (meaning that they answered “yes” to both, or “no” to both). 4 Since there are no other possibilities, those three percentages add up to 100%.

The predictor isn’t perfect (nothing ever is), but it does pretty well! When the score is low (here, below about 0.5), the likelihood that the respondent self-identified as strictly left-handed is virtually zero. When the score is high (here, above about 2.2), the likelihood that the respondent self-identified as strictly right-handed is virtually zero, and they’re about 85% likely to have identified as strictly left-handed.

For a data nerd like me, there’s something reassuring about visualizations like these. Yes, language is fuzzy, almost everything is a “spectrum,” and “reality,” whatever that means, is hard to pin down. However, the data reveal a strong underlying degree of agreement about what people mean when they talk about their own handedness. Put another way: handedness is real.

I’d argue that it’s just as real as height or grip strength, but, as with any continuous landscape we reduce to named categories—say, “short” or “tall,” “strong” or “weak”—there’s some individual “measurement error.” More significantly, people’s personal thresholds vary. Just as there’s no objective definition of “tall,” there’s no objective place to put the threshold distinguishing left- from right-handedness.

Interestingly, even when the left-handedness predictor is maxed out, about 15% of respondents still give ambiguous handedness answers. They’re not in the majority, but are they “wrong”? In cases like these, the variety of answers isn’t a human imperfection, but an essential feature of the way language is used to mark out and constantly renegotiate the way we all think about things. Without that give and take, language couldn’t evolve. There will be many more examples of this effect in the second and third parts of the book.

To accommodate the flexibility of language, I avoided putting definitions into the survey questionnaires, though that did frustrate some people—especially when, in later surveys, I used words like “intersex” and “non-monogamous,” which not everybody knows. A 64-year-old woman from Houston, Texas, let me have a (virtual) earful about it. “How come you did not include definitions for all these weird words? I spent a lot of time just looking up definitions. Are you just too hip to let us little people know WTF you are talking about?”

Dear Madam: If you’re reading, I apologize. I didn’t define the words because part of the point of the survey was to find out what they actually mean to people! This is true even for seemingly boring terms like “left-handed” and “ambidextrous.” If I had tried to define them, I’d have needed to pick a definition, and then it would likely have shifted the ground of many comments toward debates about these definitions (sometimes this happened anyway), and in the yes/no section, I’d have ended up with some unknown number of “Well, technically…” answers at odds with what people would have selected otherwise. In short, I didn’t want my finger on the scale.

Now let’s return to the “ambiguously handed” curve. Remember that the weights behind calculating this strict left-handedness score are based only on predicting the responses of people who were unambiguously left-handed. So, when people whose responses were ambiguous actually do fall in the blurry region between the strictly right-handed and strictly left-handed groups, this offers powerful evidence that those respondents aren’t making mistakes or clicking at random—they really are an excluded middle. For most of those respondents, identifying as ambiguously handed goes along with ambiguous answers to a series of other handedness questions relating to bodies, histories, and behaviors.

The same technique produces optimal question weights for strict right-handedness. The results are similar, though in mirror image. A high score correlates strongly with right-handedness and makes the probability of strict left-handedness zero, while a low score correlates strongly with left-handedness, and makes the probability of strict right-handedness zero. One subtle but significant difference, though, is that there’s a lower likelihood of an ambiguous response when the right-handedness score is high, for reasons that will soon become clear.

There’s something much less intuitive about the optimal predictor of ambiguous-handedness (again, this is a “yes” to both, or a “no” to both handedness questions).

Predicting ambiguity doesn’t work quite as well as the left-handed or right-handed predictions, which perhaps isn’t news—since in handedness as in anything else, there are few ways to be unambiguous, but many ways to be ambiguous. More surprisingly, scoring high on the “ambiguity scale” not only rules out strict right-handedness, but also does a better job of predicting strict left-handedness than of predicting ambiguity! This is a weird result. It tells us that if we start with “average” answers to every question and begin to slowly modify them to increase the ambiguity score, we’ll also be increasing the left-handedness score. If we keep going, we can overshoot, and end up in more strictly left-handed than ambiguous territory.

So in this sense, it’s more accurate to call handedness ambiguity “a little bit left-handed” than “a little bit right-handed,” since right-handedness is the average; it’s the default, and variations are defined relative to it. This isn’t just a mathematical subtlety, but a basic consequence of majority and minority—a recurring theme throughout this book.

The question weights for ambiguous-handedness are broadly similar to those for strict left-handedness—with one important exception: “Were you made to change your dominant hand as a child?” got virtually zero weight for predicting strict left-handedness, but it’s the second most positive predictor of ambiguous-handedness, just behind “Do you write with your left hand?”

An implication is that many of the ambiguous respondents were left-handed to one degree or another in childhood, but were made to switch their dominant hand. For completeness: “Were you made to change your dominant hand as a child?” has a strong negative weight for the strict right-handedness predictor. So, strongly right-handed children are made to change their dominant hand much less often—because it’s already the “right” one!

The difference becomes obvious by separately graphing the proportion of strictly right-handed people who were made to switch and the non strictly right-handed people who were made to switch.

The full effect is probably even larger than the plot shows, since many people’s handedness scores fall somewhere in the middle, even if they identify as strictly right-handed on the survey. After all, if you have some flexibility with regard to handedness as a child, you may as well go with the right-handed majority, and reap the social benefits. 5

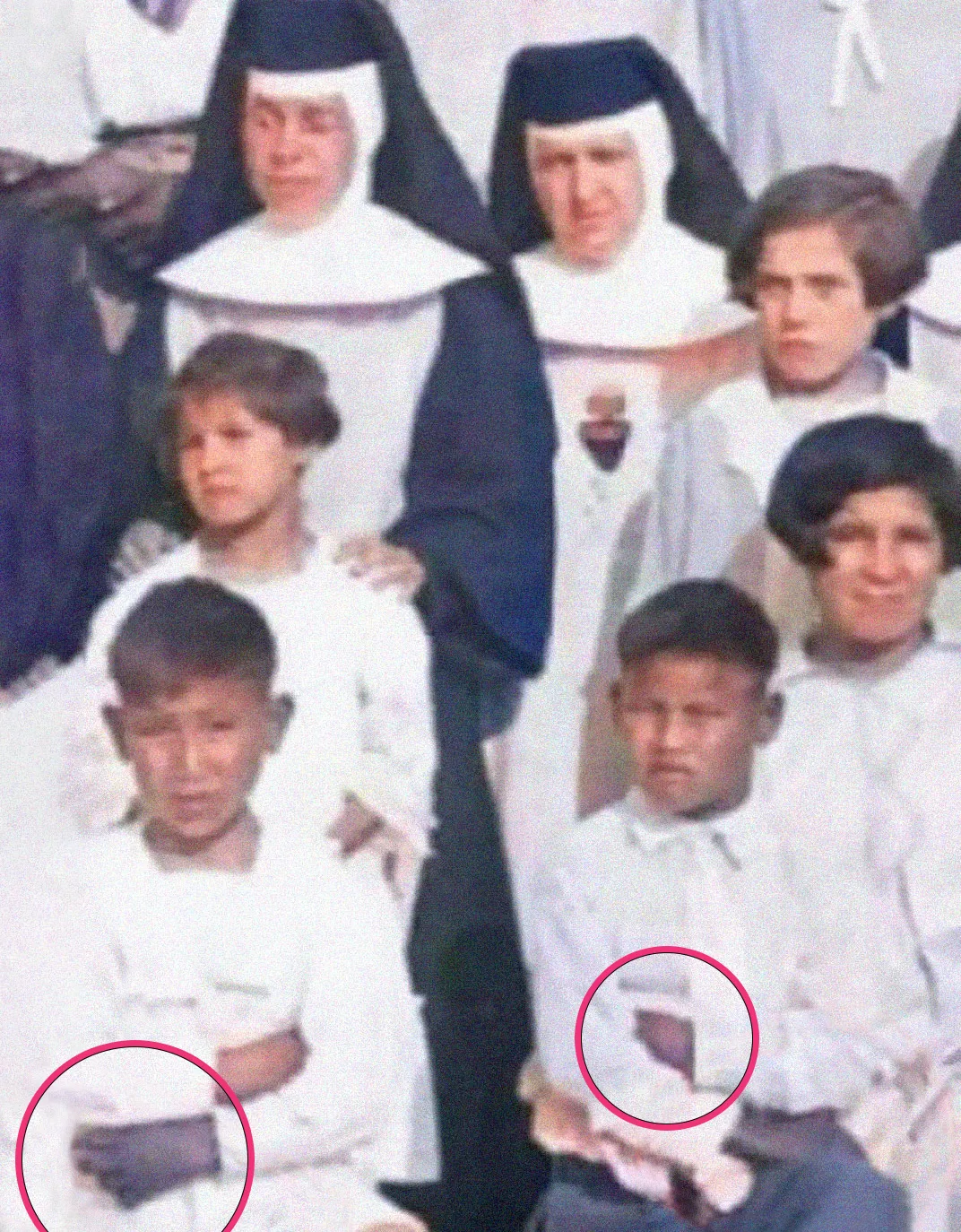

In fact, depending on where, when, and how you grew up, you may be compelled to switch, whether by parents, siblings, teachers, nuns, or other authority figures. As a 27-year-old from Phoenix, Arizona put it, “ambidextrous as a child and pushed to choose right-handedness.” Or, in the words of a 54-year-old from Southwith, Massachusetts,

My sister took the pencil out of my left hand, put it in my right hand, and said ‘You’re a (family name). We write with our right hands.’ I was in first or second grade. I used my right hand from there on.

It’s likely that many people who were similarly pushed to choose right-handedness didn’t notice it as kids or don’t remember it as adults; they just adapted. Latent signs of left-handedness may remain in these cases, whether the respondent is conscious of them or not.

People seem to remember the pressure to conform when there’s embarrassment or trauma involved, though, or when adaptation is especially hard. Those who answered “yes” to “Were you made to change your dominant hand as a child?” often had stories to tell:

Early school teachers often taped one hand to my waist to force me to always use the other. It was strange and [embarrassing] to be selected for this punishment. 6

It’s tempting to think of such negative experiences as stories from less enlightened times, long ago. That had certainly been my assumption. A 32-year-old from Long Beach, California, wrote, for instance,

I believe [my mom] did have to change, cause people were crazy back then, so I couldn’t really answer yes or no to her handedness either way, so I just said no to both.

A 67-year-old from McKinney, Texas, speaks for that previous generation:

I was naturally left-handed, but in 1950 you couldn’t get scissors, etc. for left-handed people, so my mother forced me into using my right hand. I still do many things left-handed […] So I would, to some extent, call myself ambidextrous.

There’s a likely age trend in the “forced to switch” question for non-strictly right-handed people, suggesting a generational shift underway. The large error bars suggest taking this with a grain of salt, though; the population graphed is a minority of a minority, so the counts are low. Still, very few of the youngest strictly left-handed adult respondents reported having been made to switch—under 5% between ages 18 and 22—while the number rises past 10% by age 26, and 15% by middle age. If there were enough data in the sample to add an additional age bin, the “forced to switch” percentage among older people might be even higher.

The data suggest that there’s a change afoot in how we treat left-handed children, but also that the practice of forced switching is far from ancient history. Speaking for many, a 26-year-old man from Shelburn, Indiana, wrote, “I was beat by nuns as a child to change what hand I wrote with” (yes, nuns do figure in a surprising number of these accounts). A 30-year-old woman from Sterrett, Alabama, expressed her surprise that this was even a thing:

I can’t believe the situation where I was made to change hands as a child was a question on here! I figured I was the only one in the world that my biological father spanked me when I picked things up with my left hand and until I used my right hand to pick it up with. Is there other people like me out there? I’m not alone on that?

As the numbers show, she is very much not alone.

Although I’m not suggesting any equivalence, it’s hard not to notice a parallel with the stories of people who have been subjected to “conversion therapy,” the pseudoscientific practice of trying to change someone’s sexual orientation through social pressure, psychology, or spiritual indoctrination. There, too, of course, the conversion attempt is always from the (“queer”) minority to the (“straight”) majority.

We have no good evidence that conversion therapy actually works. Many of the leaders and proponents of conversion programs over the years eventually admit that they themselves are still gay, and end up apologizing for putting so many other people through those programs. John Paulk, for example, wrote in the Advocate in 2013,

For the better part of 10 years, I was an advocate and spokesman for what’s known as the ‘ex-gay movement,’ where we declared that sexual orientation could be changed through a close-knit relationship with God, intensive therapy and strong determination. At the time, I truly believed that it would happen. And while many things in my life did change as a Christian, my sexual orientation did not. […] Today, I do not consider myself ‘ex-gay,’ and I no longer support or promote the movement. Please allow me to be clear: I do not believe that reparative therapy changes sexual orientation; in fact, it does great harm to many people. 7

Paulk is just one among at least a dozen prominent “ex-ex-gay” former leaders of such organizations. 8 Clearly the question of how malleable sexual orientation may be is both ideologically charged and can have major real-life implications. I’ll revisit this topic (as well as the deep history of conversion therapy) in later chapters.

For now, let’s consider the lower-stakes question of whether trying to change the handedness of children “works.” Adaptation does seem possible for some people, especially if they’re in the middle of the spectrum, as with a 66-year-old in Lakeland, Florida, who wrote, “I did use both as a child, but nuns in Catholic Kindergarten changed that. Glad they did actually.”

However, there are also many responses like the one below, from a 31-year-old in Dumont, New Jersey, suggesting that “handedness conversion therapy” on a left-handed kid often doesn’t produce a happily right-handed adult:

Just wanted to say thank you. So many people don’t realize that when we were forced to change our hands at a young age (“This is a right-handed world”) it forever tainted handwriting/drawing ability.

From the survey data alone, it’s impossible to guess how many people could have been left-handed tradespeople or visual artists, but never developed their gifts because they were forced to use their right hands. Clearly, harm has been done.

It’s reassuring to see that forced handedness switching is less common in the United States nowadays, though sobering that the change is so recent. Questions about the “natural” range and balance of handedness over a human lifetime may only be answerable in another generation, by which time we’ll perhaps have seen a whole cohort grow up without the pressure to switch. Or else, it could be that trying to find this “natural state of things” is a fool’s errand, because we’re such an inherently social species. Pressures to conform are ever-present, as are shifts in language and behavioral norms.

Sometimes the supposed “aberrancy” of left-handedness is given a romantic gloss, associating it not only with mental imbalance but also with artistic talent or creative eccentricity. Ellen Forney writes movingly about the “mad artist” trope in her graphic memoir, Marbles: Mania, Depression, Michelangelo, and Me: A Graphic Memoir, 2012.

Numerical weights aren’t shown, because the scale is arbitrary; doubling all of the weights, for example, wouldn’t change the prediction. What matters here is the overall pattern: whether a question is positively or negatively correlated, and how important it is relative to the others.

Nobody knows exactly why this is so, but it’s consistent with the literature. Herron and James, Neuropsychology of Left-Handedness, 171, 1980.

Once again, the numerical values on the x axis don’t matter here; they’re just a function of the arbitrary way the weights are scaled. If the weights were all doubled, for example, then the overall score would also be doubled, but the predictions would be the same; only the proportions matter. The error bars in this histogram are calculated by rerunning the whole procedure many times with random subsets of respondents “held out,” giving an estimate of how reliable the calculation is, or more precisely, how much variability is due to the limited size of the sample.

Among the much smaller number of strictly right-handed people forced to switch, some were originally left-handed or ambidextrous but now identify as unambiguously right-handed; also, some right-handed people are forced to switch due to injury to the dominant hand.

A 58-year-old woman from Palmyra, New York.

Brydum, “John Paulk Formally Renounces, Apologizes for Harmful ‘Ex-Gay’ Movement,” 2013.

Other prominent ex-ex gay figures include Günter Baum, Michael Bussee, Gary Cooper, Ben Gresham, Noe Gutierrez, John Smid, Peterson Toscano, Anthony Venn-Brown, McKrae Game, and David Matheson.