In the Middle Ages, humanity was resource-constrained. As ever, the ruling class had a lot more than its fair share, but redistributing their extra food among all of the hungry people still would have left everyone hungry—indeed, during famines, even the nobility tended to starve.

Today, aggregate wealth doesn’t constrain human wellbeing, but uneven wealth distribution does. This much is widely understood—nobody would need to go hungry anymore, if only the resources could quickly get to where they are most needed. What’s less widely understood, though, is the profound effect of uneven wealth distribution on birth rate, which is arguably even more important to human welfare today than hunger.

The negative correlation between wealth and fertility was obvious even in Malthus’s time. He noticed that the aristocracy had fewer children than the poor, but whereas he framed the difference in moral terms, 1 in reality the effect is demographic and economic. As Our World In Data puts it when comparing national statistics,

In all countries we observed the pattern of the demographic transition, first to a decline of mortality that starts the population boom and then a decline of fertility which brings the population boom to an end. The population boom is a temporary event.

In the past the size of the population was stagnant because of high mortality, now country after country is moving into a world in which the population is stagnant because of low fertility. 2

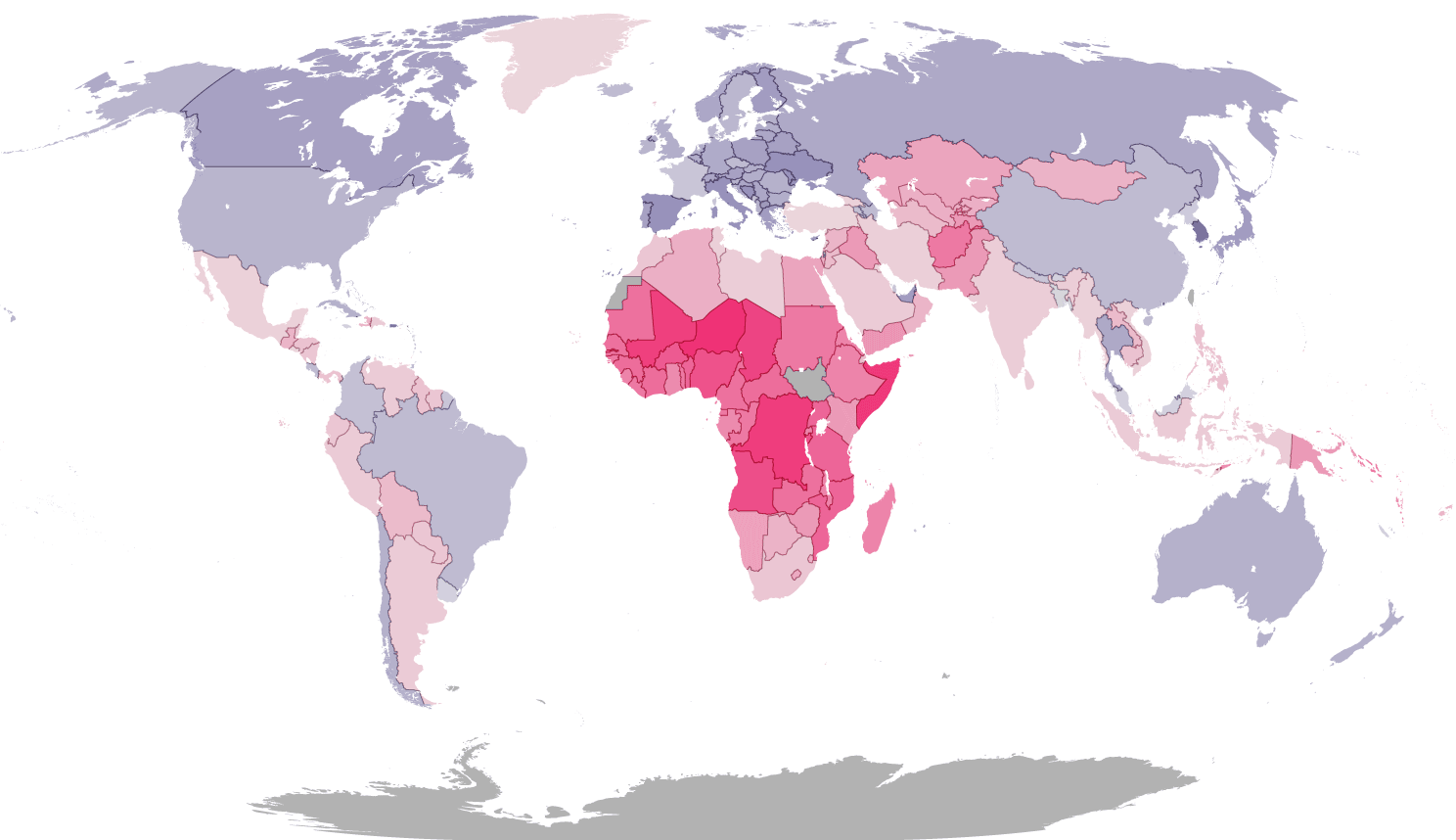

The US, in other words, is typical among rich countries. Indeed, when the UN runs population size simulations based on historical data for the more economically developed regions of the world, they conclude that as of now, population in these places has already peaked and will likely not increase further. 3 Nearly all remaining worldwide population increases will come from the less economically developed parts of the world, and the rate at which their fertility declines in turn will be a function of how quickly they develop economically.

But why is this happening? The availability of birth control in advanced economies is clearly part of the story. Malthus assumed that inextinguishable “passion between the sexes” 4 automatically led to serial pregnancies and an endless parade of offspring, which could only be stemmed through heavy-handed intervention by church or state—much as China eventually tried with the “one child” policy. At the time, he may not have been far off the mark: sexual impulses are powerful, patriarchy suppresses women’s choices, and in 1798, birth control options left much to be desired. Reusable condoms did exist, typically made from chemically treated linen or animal gut. 5 They could be bought at chemist shops, barbershops, and theaters, but they weren’t cheap. In his memoirs, the infamous libertine Giacomo Casanova (1725–1798) describes blowing up his condom before use to inspect for holes. 6 This was very much a gentleman’s game. It would have been regarded as scandalous for a woman—either married or unmarried—to buy one, and for a typical sex worker, such a condom might have cost several months’ pay. 7

Condoms are instances of what Malthus called “preventive checks,” which lead to fewer births, as opposed to “positive checks” that kill the young. While positive checks decrease when social and medical technologies improve, preventive checks increase. The Pill, which first became available in 1960, was without a doubt the single most important such technology. It put contraception in women’s hands; it was discreet, safe, reversible, reliable, affordable, and non-invasive; and it didn’t involve doing anything special during or immediately before sex. It was a dream come true. No prior method had even come close to fulfilling all of these desiderata.

Of course, condoms have also gotten a lot cheaper and better, and we now have a number of other good contraceptive options too. Abortion and elective sterilization (increasingly, vasectomy for men, as it’s a far less invasive procedure than sterilization for women) have been important preventive checks.

Birth control technologies aren’t the whole story, though. They have emerged alongside the suite of social innovations described in Chapter 9—changes in the workforce, economy, laws, and customs that make it possible (and attractive) for people to live fulfilling lives with few or no children.

Until recently, it’s been extremely difficult for women to stay independent and single, or to divorce. Plenty of older female survey respondents describe being trapped in marriages they don’t really want, due to some combination of social pressure, the obligations of motherhood, and economics (again, see Chapter 9). Being a single woman has gotten a lot easier, though, and that also has lowered birth rates.

Then, there’s the greater social acceptance of lesbian and gay couples, or the many other configurations in which love, sex, and companionship aren’t necessarily geared toward producing kids. Of course same-sex couples can have kids, but it won’t “just happen” due to a missed pill or a slipup in the bedroom. It’s something they have to want, choose, and work for. Today, even for heterosexual couples, having children is increasingly seen as a deliberate choice, rather than an unexamined default.

For that matter, the same is true of being partnered at all. The sociologist Eric Klinenberg wrote a book about this phenomenon in 2013 whose title pretty much gives away the plot: Going Solo: The Extraordinary Rise and Surprising Appeal of Living Alone.

[O]ur species has embarked on a remarkable social experiment. For the first time in human history, great numbers of people—at all ages, in all places, of every political persuasion—have begun settling down as singletons. […] [T]oday, for the first time in centuries, the majority of all American adults are single. The typical American will spend more of his or her adult life unmarried than married, and for much of this time he or she will live alone. 8

As Klinenberg notes and the survey data confirm, this is, foremost, an urban phenomenon. About 47.5% of Americans over 18 are married. 9 While a solid majority of countryside dwellers at all ages over 35 are married, for city dwellers, the average barely reaches half between ages 35–60; only a minority are married outside that 25 year window. This pattern is very different from the midcentury Flintstones era, when being an unmarried adult caused one to be seen as odd or a failure; even in the countryside, that’s obviously no longer the case. In 1950, only 9% of American households consisted of single adults. 10 By 2022, the figure had risen to 29%. 11

Klinenberg is at pains to point out that for many, “going solo” doesn’t imply a lonely life, nor is it about prioritizing freedom and lack of commitment over intimacy. In this sense, “solo” is a misnomer: “Living alone gives us time and space to discover the pleasures of being with others.” Singletons often have multiple close connections, whether social, sexual, or romantic. These may be stable for long periods and may involve long-term commitments, or they may shift over time, but there’s no indication that singletons are as a population less connected or emotionally healthy than married people. Social fulfillment while single is easier in the city, though, where there’ll tend to be a lot more of “your people” around, whomever they are. Presumably that’s why this trend started in cities, and is so much more pronounced there.

Sexuality itself seems to be evolving in a related way. People are deciding what (and who) they want to do more intentionally, rather than just acting out a received script. Being intentional only works, however, if the economic and social conditions allow for it. In particular, it only works in a sexually egalitarian society where women are able to survive and thrive without being dependent on a man—a change from the status quo for most agricultural societies for thousands of years, in both monogamous and polygynous variants. A happy irony results: Letting go of patriarchy makes men freer too.

Reproductive choice is key to self-determination for both women and men. It’s especially important for women, though, given that the costs and risks of labor, childbirth, nursing, and child care are disproportionately theirs to bear, even with the “post-gendering” technologies described in Chapter 15. That so many women, including an increasing number who are unpartnered, still willingly choose to take these burdens on speaks to the fact that having kids remains intrinsically rewarding for many (though by no means all).

Why do we do it? As economic sociologist Viviana Zelizer puts it, “A national survey of the psychological motivations for having children confirms their predominantly sentimental value.” A child, she wryly observes, “is expected to provide love, smiles, and emotional satisfaction, but no money or labor.” 12 These intangibles do count for something. But despite the delights of having children, as we’ve seen, few potential mothers in rich countries with reproductive choice decide to have large numbers of them: the average is below two.

Can we trust that this average truly reflects women’s uncoerced choices? Reproductive choice isn’t ideal in the US, especially in the wake of successful multi-decade campaigns from conservative and religious groups to roll back Roe v. Wade. Thus the US fertility rate may still be skewing high, as plenty of American women today with limited access to social support, money, information, health care, contraception, and abortion will suffer unwanted births. On the other hand, financial precarity prevents some women from having wanted babies. Which effect is bigger remains uncertain.

Overall, the US fertility rate is in the same ballpark as that of many other developed countries, such as France and the UK, which have full national access to healthcare, including abortion and subsidized childcare. Perhaps, then, we are starting to get a sense of how many babies potential mothers choose to have on average when they can make that choice freely—although, given the inevitable role of social transmission, 13 an unbiased measurement would be difficult, even in principle. The World Bank has run surveys asking mothers in many countries how many births they ideally would have wanted, and how many babies they’ve actually had, to get a sense of unmet demand for contraception; almost inevitably, the wanted births are fewer, but only by a bit. 14 In the 2019 data, mothers in Colombia, for instance, wanted 1.6 babies, and had 1.86; in Mali, they wanted 5.5 babies, and had 5.88. As ever, desires, norms, and realities are connected by social feedback loops.

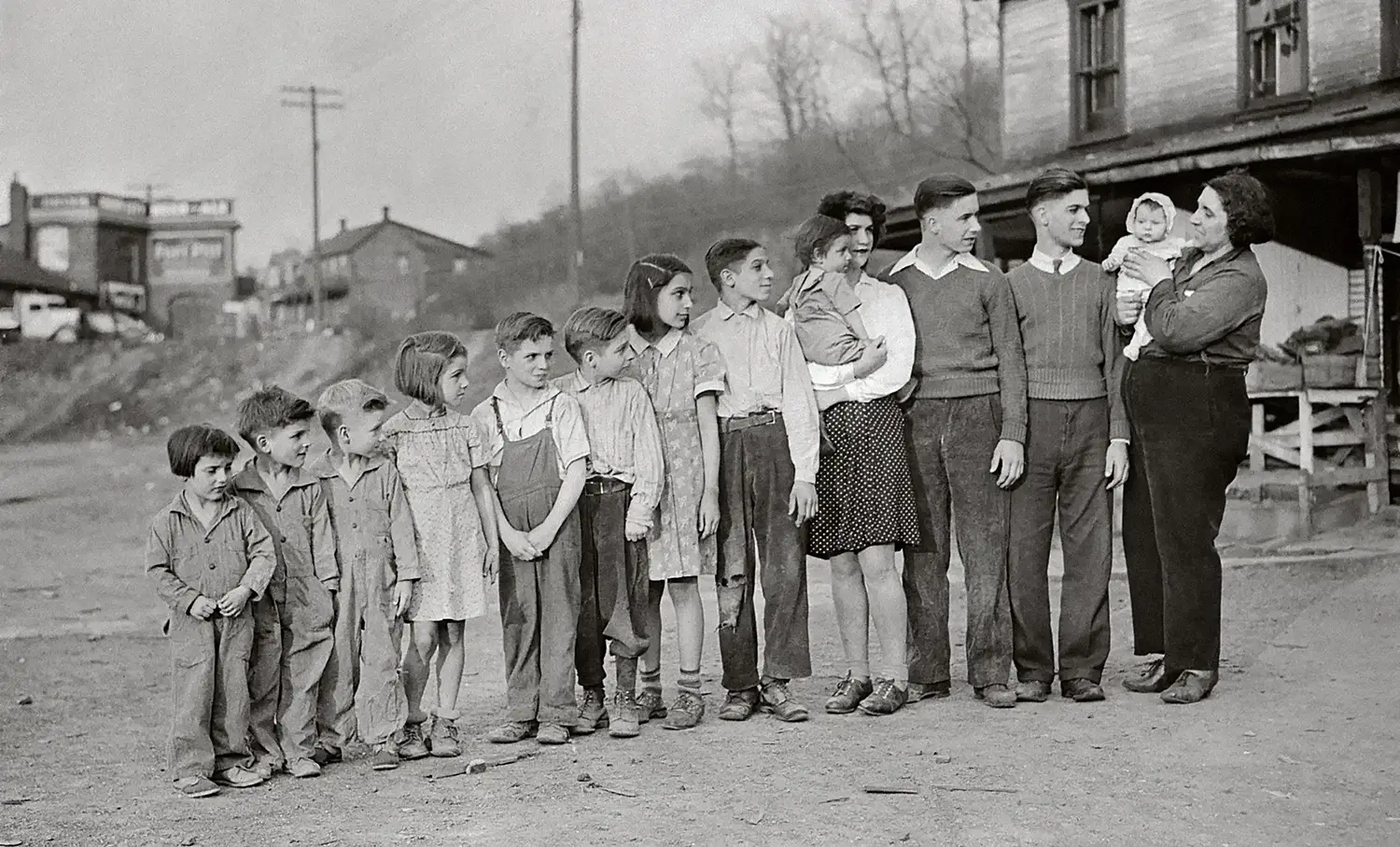

In the developed world, poorer families have more children on average; the converse holds as well, though: large numbers of children further impoverish those families. As Zelizer observes, nowadays kids don’t just fail to bring money into the household—“They are also expensive.” 15 This can lead to long-running intergenerational cycles of poverty. Or, to turn the situation on its head, having fewer children can mean substantially more resources per child, as well as a better life for the parents.

So, here’s a puzzle. Why do poor people have so many kids? Or historically, if kids cost their parents so much money, why would we have been raising so many more of them back when everybody was so much poorer? Could it be that we were impoverished because of our high fertility?

In fact, it was the opposite. Children used to enrich families, not impoverish them:

In sharp contrast to contemporary views, the birth of a child in 18th century rural America was welcomed as the arrival of a future laborer and as a security for parents later in life. The economic value of children for agricultural families has been well documented by anthropologists. 16

Urbanization during the Industrial Revolution didn’t immediately change this calculus, either. With their nimble fingers and modest needs, children could be good little factory workers too, back in the days before that was frowned upon! 17

Agricultural child labor has always been more common, though, due to correlations among economic development, automation, and the shift away from subsistence agriculture. The pattern still holds today. Among Niger’s 17 million citizens, for example, agriculture remains the primary economic activity, and 43% of children between the ages of 5 and 14 work. 18 Recall that Niger has a world-topping total fertility rate of about 7 children per woman. Overall, about one fifth of all African children, or 72 million, are laborers—a higher proportion than on any other continent—and 85% of this child labor is agricultural. 19

Today, only 1% or so of American women have as many children as the average in Niger, but remember that this wasn’t always so. Back in 1922, Henry Stanton considered seven kids entirely reasonable, though he cautioned against fourteen, “of whom seven are likely to die, while the numerous successive births wear out and age the unfortunate mother.” 20

Urbanization was less advanced in 1922, but its inverse correlation with fertility had been noticed long before Stanton’s day. He and his contemporaries still thought of children as generators of wealth, though, and so concluded that the trend toward fewer children must have been cultural—moreover, a deplorable “perversion,” made possible only by the cushiness of life in a rich country:

Material changes have taken place in the birth rate of a number of countries during the past fifteen or twenty years which […] do not seem to depend on such things as trade, employment and prices; but on the spread of an idea or influence whose tendency must be deplored, that of “birth control,” a phrase much heard in these days.

The fact that a decline in human fertility and a falling birth rate are most noticeable in the relatively prosperous countries is a proof that it does not proceed from economic causes; but is due rather to the spread of the doctrine that it is permissible to restrict or control birth. In such countries as the United States, England, and Australasia, where the standards of human comfort and living are notoriously high, the decline in the birth rate has been most noticeable. 21

Stanton was thoroughly mistaken; the reality is both cultural and economic. Birth control technologies and women’s rights are part of the picture. But also, as societies transition away from agriculture, children go from being an economic asset to a costly choice—which means opting to have fewer of them, and perhaps, accordingly, thinking of them as more precious: a luxury, rather than an investment.

If we need any further evidence of how fundamental economics are to fertility, we need only consider the fertility rates of the richest oil states: Kuwait, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Norway, Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain. 22 Norway, the outlier here, is a Scandinavian liberal democracy and has had a fertility rate below two since 1975. The Gulf states, though, were economically undeveloped religious patriarchies before oil money began flowing in—which was practically yesterday. They all had fertility rates of around 7—higher than the poorest countries today—as recently as 1960. By 2017, their fertility rates were comparable to that of Norway, despite still being religious patriarchies with few women’s rights.

Let’s consider the political implications of the inverse relationship between wealth and fertility. Based on what we now know, we’d expect lower fertility in the city than in the countryside, and indeed, as we’ve seen, this is the case. Breaking down fertility rate by age reveals that not only do women in the countryside have children at a faster pace, but also that they start having children younger. Remember that to calculate a rate of population growth, one needs to take into account not only how many children women have on average by menopause, but also the generation time, which I’ve arbitrarily fixed at 30 years. Since urban mothers tend to have children later in life, though, their typical generation time is longer. This decreases urban fertility relative to the countryside still further.

Even in the American countryside, though, the fertility rate is far from that of the old days—or of the developing world. The average only exceeds two for women well beyond menopause, highlighting how the average number of children per potential mother in the countryside (and, indeed, everywhere in the US) has been in decline for decades. The generation that has just reached menopause had children at a rate well below replacement, both in the city and in the countryside. Hence people with high TFRs in sparsely populated ZIP codes are a small minority, and are “living in the past” in several senses: their cultural norms belong to an earlier generation, they themselves are typically older, and as a result their average fertility rate reflects that of a previous generation.

Running the fertility calculations for all white women in the US yields an even lower total fertility rate of 1.27. Once again, this is unsurprising, since lower fertility correlates with wealth and privilege. It also implies that even if the US were to stop admitting immigrants, its population would still be rapidly becoming less white over time.

There are some political ironies here. If the ethno-nationalist right is concerned about being demographically “replaced” by non-white people, they should advocate for robust foreign aid, racial equity, and abortion rights. More foreign aid would lower fertility rates abroad, reducing immigration from poorer countries (both by lowering their populations over time and by increasing their quality of life, making their inhabitants less keen to leave); and greater racial equity in the US, together with freer access to abortion, would more quickly lower the fertility rate of non-white people at home.

_crop.webp)

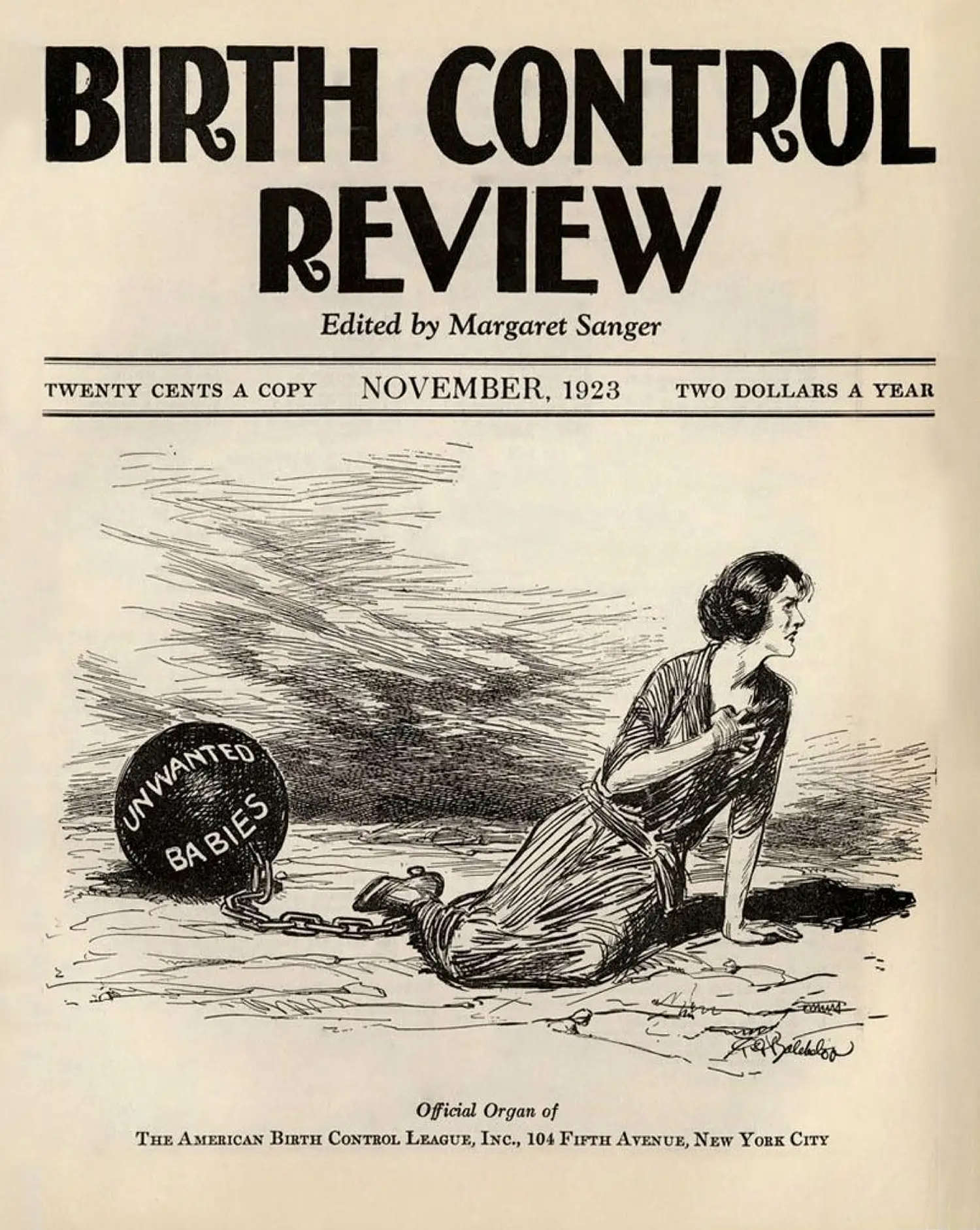

This last was, in fact, one of the arguments marshaled by Margaret Sanger (1879–1966), the founder of Planned Parenthood and the driving force behind the development of the Pill. Sanger worked relentlessly for women’s reproductive rights, but was also associated with the eugenics movement and enthusiastically cited demographic studies by Nazi researchers. (Another good reminder, regardless of one’s politics today, that it’s hard to find either perfect heroes or perfect villains—especially when we judge historical figures by today’s moral yardstick.) In her 1920 book Woman and the New Race, Sanger wrote,

If we are to develop in America a new race with a racial soul, we must keep the birth rate within the scope of our ability to understand as well as to educate. We must not encourage reproduction beyond our capacity to assimilate our numbers so as to make the coming generation into such physically fit, mentally capable, socially alert individuals as are the ideal of a democracy.

The intelligence of a people is of slow evolutional development—it lags far behind the reproductive ability. It is far too slow to cope with conditions created by an increasing population, unless that increase is carefully regulated.

We must, therefore, not permit an increase in population that we are not prepared to care for to the best advantage—that we are not prepared to do justice to, educationally and economically. We must popularize birth control thinking. We must not leave it haphazardly to be the privilege of the already privileged. We must put this means of freedom and growth into the hands of the masses. 23

“A new race with a racial soul” is a very unfortunate turn of phrase, though its connotations would have been somewhat different at the time. Such passages, along with Sanger’s ambiguous attitude toward eugenics, have led to a great deal of belated soul-searching, apology, and disavowal on the part of Planned Parenthood. 24 Still, Sanger’s main point here is that birth control should not remain the prerogative of the Casanovas of the world; it must be accessible to the poor, who, in a post-agricultural society, can least afford to raise large families. She understood clearly that birth control is both enabled by, and enables, economic mobility and development, particularly in the city.

Sanger’s idea has withstood the test of time. While the project of universal access to birth control is unfinished, we’ve now reached a point where preventive checks are doing more to decrease our numbers than positive checks used to—not only among Americans, but soon, worldwide. The exponential logic of the population bomb has been disarmed, drawing our brief period of unchecked growth to a close. Now, we have an unprecedented choice: What will a post-growth humanity look like?

This sentiment has been echoed by many moralizers before and since, e.g. in William Acton’s characterization of the lower classes as lustful and lacking in self-control—see Chapter 9.

Roser et al., “World Population Growth,” 2013.

We can take the “medium fertility” scenario as a reasonable best guess, though the most recent data seem more consistent with the even faster population decline of the “low fertility” curve.

Malthus, An Essay on the Principle of Population, 1798.

These would be supplanted by thick rubber sheaths in the 19th century, which, while cheaper, were… distancing.

Casanova, History of My Life, 1966-1971.

Collier, The Humble Little Condom: A History, 120–21, 2007.

Klinenberg, Going Solo: The Extraordinary Rise and Surprising Appeal of Living Alone, 3–4, 2013.

Like the graphs themselves, these figures are calculated by weighting the averaged responses from groups of survey participants to match the overall demographics of the United States (see the Appendix for details).

Klinenberg, 4–5.

U.S. Census Bureau, “Census Bureau Releases New Estimates on America’s Families and Living Arrangements,” 2022.

Zelizer, whose work focuses on the attribution of cultural and moral meaning to the economy, wrote these rather tart words in her 1985 book, Pricing the Priceless Child. Perhaps her son, Julian, took them as a challenge; in 2007 he joined her at Princeton’s Department of History and Public Affairs, to form the first mother-son professorial team in Princeton’s history. Zelizer, Pricing the Priceless Child: The Changing Social Value of Children, 1985; Rubin, “Prof: Election Dynamic Bodes Well for the Jews,” 2008.

See Chapter 7.

Our World in Data, “Children per Woman vs. Number of Children Wanted,” 2023.

Zelizer, Pricing the Priceless Child: The Changing Social Value of Children, 3, 1985.

Zelizer, 5.

See Babbage’s notes on child factory labor in On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures in Chapter 15.

Bureau of International Labor Affairs, “2021 Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor: Niger”; Wikipedia, “Agriculture in Niger,” 2020.

International Labour Organization, “Global Estimates of Child Labour: Results and Trends, 2012-2016,” 2017.

Stanton, Sex: Avoided Subjects Discussed in Plain English, 47, 1922.

Stanton, 48–9.

These are the top ranking oil producers per capita, less Brunei, Oman, Libya, and Guyana, which have significantly lower mean and median wealth.

Sanger, Woman and the New Race, 44–5, 1920.

Planned Parenthood, “Opposition Claims About Margaret Sanger,” 2021.