Abi Bechtel, a teaching assistant at the University of Akron and mother of three, was fed up. It was 3:36pm on the first of June, 2015. She was standing in front of aisle E11 in the toy department, phone raised, taking a picture of the sign: “Building Sets,” and… “Girls’ Building Sets.” Abi tweeted the photo alongside four words: “Don’t do this, @Target.” 1

It worked. A couple of months and many retweets later, Target responded by announcing they’d be phasing out unnecessary gendered signage. In the following years, they built on the policy by introducing gender-neutral bathrooms, children’s bedding, and clothes. 2

Toca Boca, the clothing company Target partnered with to help drive the change, was making its first foray into brick-and-mortar retail. Originally a casual game company, it was known for its popular gender stereotype-defying apps, Toca Boca Hair Salon and Toca Robot Lab. Much of the colorful imagery featured on the kids’ clothes—from “a coral-colored T-shirt of a mean-mugging sloth donning a baseball cap, with the word ‘Fast’ printed underneath” to “a purple pile of poop”—were “characters ripped straight from the apps of Toca Life, […] digital games that emphasize role playing and are set in common locales such as farms or city streets.” 3

The hyper-gendered world of children’s clothing had long been dominated by franchised media relentlessly flogging a pink/blue, unicorn/dinosaur binary. Many of the big brands used to be anchored by prime time TV shows and cartoons targeting either girls or boys. The media landscape had been changing, though, crumbling into a demographic fractal of competing channels, content streams, and social feeds. Among a generation growing up “digitally native,” as the marketers put it, something new seemed to be afoot, a gender-neutral aesthetic spreading from the online to the offline world.

Of course parents are the ones who need to open their wallets to buy this stuff for their kids, so mounting frustration from people like Abi Bechtel doubtless played a role. However, Toca Boca wasn’t just following an ideological premise, or responding to the demands of parents. They were, per their digital roots, data-driven, using observational testing to understand “what characters users most like and identify with, as well as the most appealing colors, what kids think is funny, and what scenarios skew too heavily toward a certain gender or seem to exclude some players.” The more inclusive a design, the more universal its appeal. Online, “scale the user base” has always been the mantra. Target doubtless saw the business sense in this idea.

Predictably, though, the retailer’s new policies stoked controversy among social conservatives. Writing for conservative media outlet TheBlaze, Matt Walsh lamented,

Progressives see the toy industry like they see everything: an ideological battleground, another politicized arena to defeat traditional concepts of gender and usher in this new ambiguous dystopia where kids can live as amorphous, genderless, pansexual blobs of nondescript matter. […] I won’t attempt to defend every gender stereotype or “gender norm,” but I do subscribe to the radical theory that boys and girls are different and distinct from one another in complex, concrete, and important ways, and many of the dreaded “norms” are, well, normal and biological. It is precisely our role as parents to help our kids “conform” to their gender, to their identity, and grow from boys and girls into well adjusted, confident masculine men and feminine women. 4

Walsh dramatizes just how central the gender binary can be to traditional ideas about identity—or mere personhood—by describing those who don’t hew to the binary as “amorphous […] blobs of nondescript matter.” Yet curiously, he also implies that children need to be socialized or taught to be masculine or feminine—that “nature” needs to be propped up and reinforced by culture. This view is reminiscent of John Money’s discredited (and at the time, progressive) theory of the gender binary as socially constructed. Money’s whole clinical pediatric practice was dedicated to the project of helping kids “conform,” so that they could grow up to become “well adjusted, confident masculine men and feminine women.”

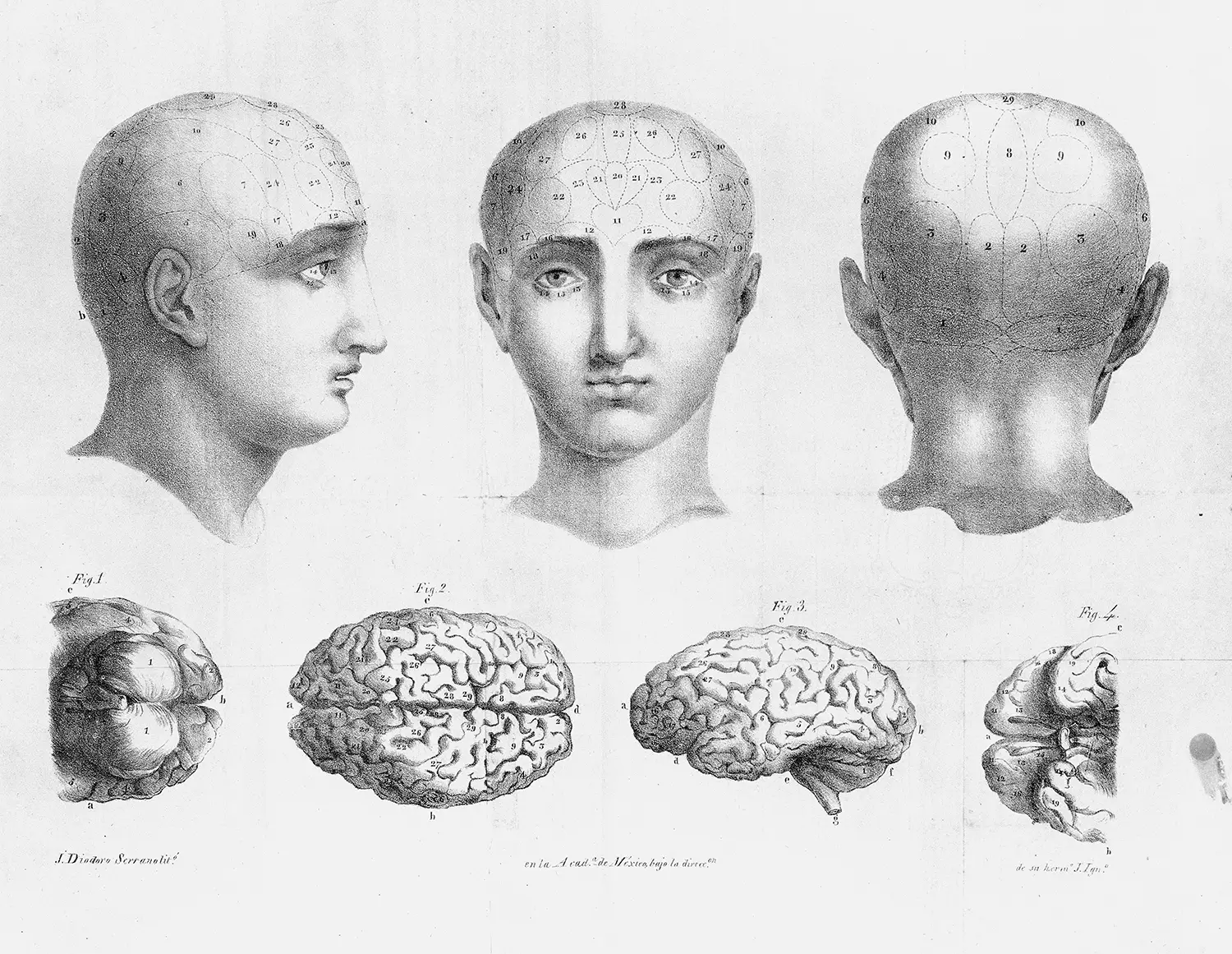

As our deepening understanding of intersexuality has made obvious, the biology of sex is more complex than a binary either/or, but it’s still the case that most of our bodies can be meaningfully classified along this axis. The big question is whether the same applies to the brain. Is there, in any quantifiable sense, such a thing as a “female brain” or “male brain,” independent of learning and socialization?

This remains hotly contested. A whole scientific literature shows that both the absolute and relative sizes of various brain regions do vary, on average, by sex. 5 Some studies have attempted to relate these differences to cognitive skills, but here the results are murky, generally showing weak or inconclusive results, relying on small numbers of subjects, and using highly artificial tasks. Drawing firm conclusions is nearly impossible since, in the real world, nature and nurture are inseparable.

In her 2019 book Gender Mosaic: Beyond the Myth of the Male and Female Brain, 6 Israeli neuroscientist Daphna Joel points out that individual variability in both skills and brain structures is far larger than the average difference between the sexes, with a majority of people exhibiting what she calls a “mosaic” of more typically masculine or feminine brain regions and cognitive traits. 7 In other words, at least on the basis of today’s coarse physical and functional measurements, most of us have an “intersex brain.”

Using these findings as a springboard, Joel makes the radical-sounding case for gender abolition in most areas of life. She doesn’t deny that our bodies (and, to a lesser extent, our brains) vary by sex, but she believes we attribute far too much importance to this particular axis of variation—with profoundly negative consequences.

For instance, she finds it frustrating—as do many, myself included—that a phrase like “woman scientist” can be used to describe her, while “man scientist” sounds redundant in describing me; I enjoy the privilege of simply being a “scientist.” The situation is a grown-up analogue to “Building Sets” versus “Girls’ Building Sets.” When I type “woman scientist” into Google, I get 10.2 million hits, but only 2.4% as many—247 thousand—for “man scientist.” “Man scientist” is just not a thing. Of course the search result doesn’t reflect that 97% of scientists are women; quite the opposite. It’s just that qualifiers in language always attach to minorities, as described for handedness back in Chapter 2. 8

Transfeminist author Julia Serano calls this the “marked/unmarked” distinction, noting that one doesn’t even have to be in the minority to be “marked”:

[W]omen make up slightly over fifty percent of the population, and yet we are marked relative to men. 9 This is evident in how people comment on, and critique, women’s bodies and behaviors far more than men’s, and how things that are deemed “for women” are often given their own separate categories (e.g., chick lit, women’s sports, women’s reproductive health), whereas things that are “for men” are seen as universal and unmarked. 10

There’s often an insinuation implied. It would sound odd to describe an acquaintance as a “blue-eyed scientist,” for instance—although blue eyes are also a minority—because eye color, being unmarked, isn’t deemed relevant to anything else—such as being a scientist. 11 Every time we use the phrase “woman scientist,” we’re admitting that, in our minds, being a woman is somehow relevant to, and perhaps even in tension with, being a scientist.

For some, the underlying bias is explicit. At a 2005 conference hosted by the National Bureau of Economic Research, Lawrence Summers, then president of Harvard University, argued that female scientists were underrepresented due to biological factors—meaning, women simply aren’t as interested in or as good as men at doing science. 12 Software engineer James Damore floated a similar claim about the underrepresentation of women in engineering in a widely circulated memo at Google in 2017. 13

These are old claims. They used to take more extreme forms; in the 19th century, women were commonly held to be incapable of abstract or creative thought. This was one rationale for barring them from higher education in fields like mathematics—for what would the point be?

Consider the intellectual partnership between Charles Babbage (1791–1871), inventor of the Analytical Engine (a steampunk precursor to the modern computer) and Ada Byron King, Countess of Lovelace (1815–1852), who wrote the first ever computer program. 14 As a woman, Lovelace’s only route to higher math was private tutoring. (Being a countess did have its benefits; social class introduces a whole other dimension of inequality.) Yet even her relatively progressive math tutor, Augustus De Morgan, expressed his skepticism that she could make a real contribution in a cautionary letter to Ada’s mother, Lady Byron, in 1844: “[T]he very great tension of mind which [wrestling with mathematical difficulties requires] is beyond the strength of a woman’s physical power of application.” 15 Astonishingly, he wrote this letter soon after Lovelace’s seminal publication describing how to program the Analytical Engine, a masterwork of mathematical creativity and arguably the founding document of the entire field of computer science!

So, between low expectations and lack of access to higher education, Victorian women encountered great difficulty contributing to science, technology, engineering, or math, yet the near-absence of women in these fields was considered the very evidence that they weren’t capable. When, against all odds, women still managed to excel, as Lovelace and a few others did, their successes went unacknowledged, or were regarded as freakish.

Cesare Lombroso attempted to put these attitudes on a “scientific” footing in his 1893 followup to The Criminal Man, entitled The Criminal Woman, the Prostitute, and the Normal Woman. 16 Echoing commonly held beliefs at the time, he asserted not only that “Compared to male intelligence, female intelligence is deficient,” 17 but also that “woman is always fundamentally immoral.” Further,

Normal woman has many characteristics that bring her close to the level of the savage, the child, and therefore the criminal (anger, revenge, jealousy, and vanity) and others, diametrically opposed, which neutralize the former. Yet her positive traits hinder her from rising to the level of man, whose behavior balances rights and duties, egotism and altruism, and represents the peak of moral evolution.

Ugly as this characterization is, it might seem like it could at least have afforded an enterprising woman a route up the patriarchal ladder by being, as Rex Harrison drawled in My Fair Lady, “more like a man”; 18 but this wasn’t the case. If a woman failed to be submissive or to conform to gendered expectations, then her “masculine” character made her a degenerate, just as “feminine” traits would for a man:

Degeneration induces confusion between the two sexes, as a result of which one finds in male criminals a feminine infantilism that leads to pederasty. To this corresponds masculinity in women criminals, including an atavistic tendency to return to the stage of hermaphroditism. […] To demonstrate the presence of innate virility among female prisoners, it is enough to present a photograph of a couple whom I surprised in a prison. The one dressed as a male is simultaneously so strongly masculine and so criminal that it is difficult to believe she is actually female.

It was a no-win situation.

Gender bias has diminished since the 19th century, but by how much? Recall that intersex medical literature from the 1960s still took for granted that “Most married [chromosomally male] women […] take part in extra-household activities which they often pursue with great success because of their above average intelligence.” 19

While recent literature on sex-based cognitive differences hasn’t reached any clearcut conclusion, the lingering effects of low expectations, social pressure, and discrimination remain obvious—not just anecdotally, but in large-scale, real world findings. Perhaps most famously, a shift toward gender equality in orchestras began taking place after “blind” auditions became the norm some decades ago, raising the percentage of women in the United States’s five highest-ranked orchestras from 6% in 1970 to 21% in 1993. 20 Today, women make up half of the New York Philharmonic. 21 Clearly it wasn’t the case that men make better violinists, though that claim would have seemed plausible in 1970.

A similar real-world experiment has been conducted in the field of software engineering using GitHub, the world’s largest social coding platform. 22 When an engineer adds code to a project—a process that requires approval from a project owner—their gender may be either visible or invisible, depending on their user profile. A 2016 study of 3 million code contributions from 1.4 million coders found that women’s code was accepted more often than men’s… unless the contributors were outsiders to a project and their gender was visible. Under those conditions, men’s contributions were accepted more often.

A more recent study at Google found that “pushback” on code contributions, meaning requests for additional work before the contribution would be accepted, were more extensive not only for women, but also for older and nonwhite engineers. 23 Unfortunately, in a corporate setting where teammates all tend to know each other, gender-blind coding is a lot harder to pull off than on worldwide social coding projects with many contributors.

Academia is no better. A sweeping 2021 review identified sources of gender bias in science at every career stage, noting among many other effects that “several studies where the identity of the authors was experimentally manipulated demonstrated that conference abstracts, papers, and fellowship applications were rated as having higher merit when they were supposedly written by men.”

So, women (along with other historically underrepresented minorities) still struggle against powerful bias in fields like science and engineering. Yet when we’re able to measure their real-world contributions on a level playing field, under gender-blind conditions, we don’t see evidence of the inferiority Summers, Damore, and others insinuate. The insistence that such insinuations are harmless questions or mere “food for thought” angers many advocates for gender equality, as such insinuations reinforce the biases that pose the greatest obstacles to equality.

Musical performance, science, and engineering in the modern world have something in common: an increasing degree of disembodiment relative to the more physical presence, and the more physical kind of labor, that predominated in centuries past. Today, many humans are information workers, and many of our relationships with each other are pure information relationships; our genitals, and more broadly, the sexual differences between our bodies, just aren’t relevant anymore to these forms of work or relationships.

I’m not denying the raw physicality of live music, the way you can feel it in your body, the way it can move you to get up and dance. In the end, though, if you’re a violinist, what really counts is what comes out of the violin—not what’s on the album cover, or under your clothes. In evaluating code or a scientific paper, the irrelevance of sex and gender is even more obvious.

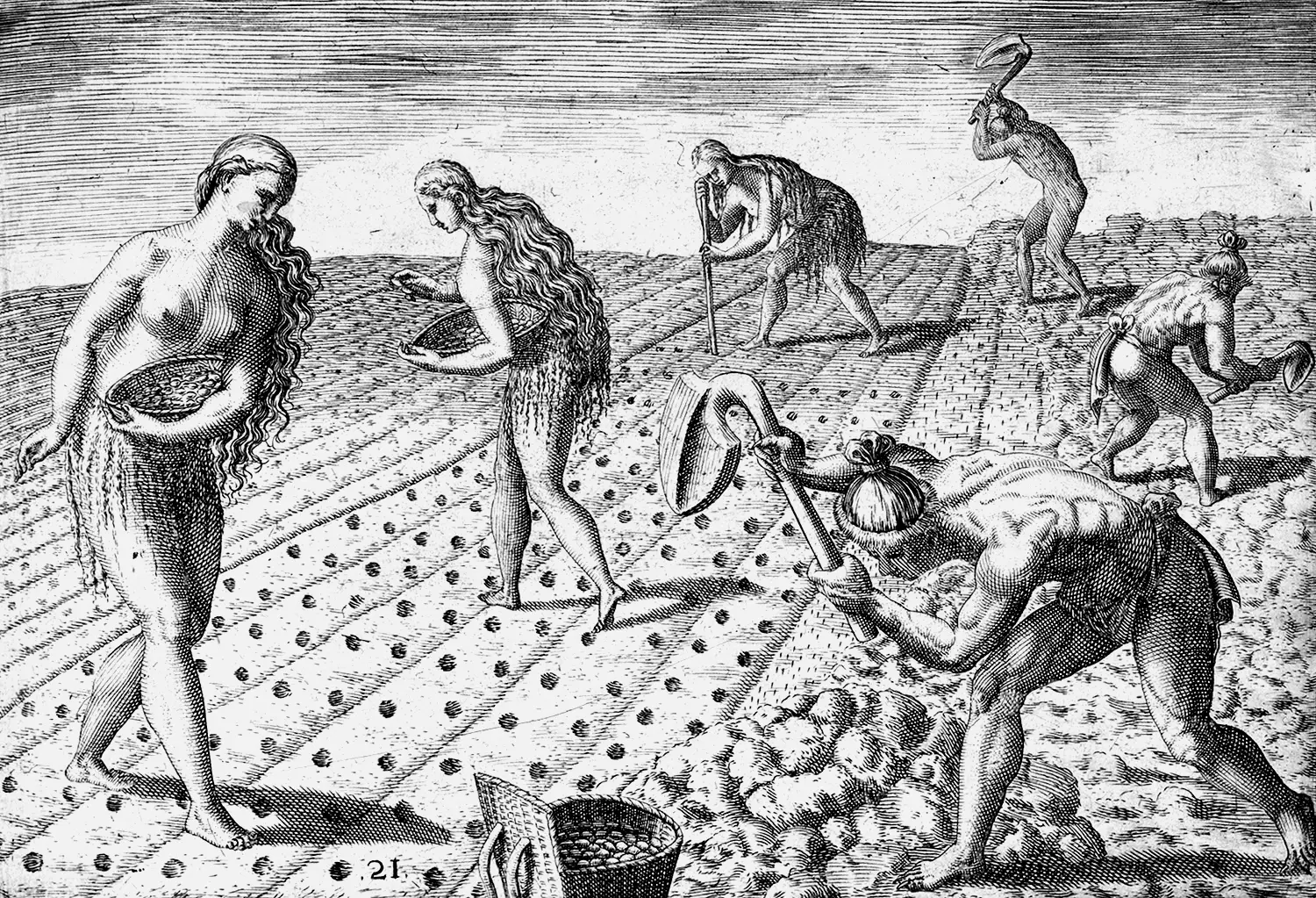

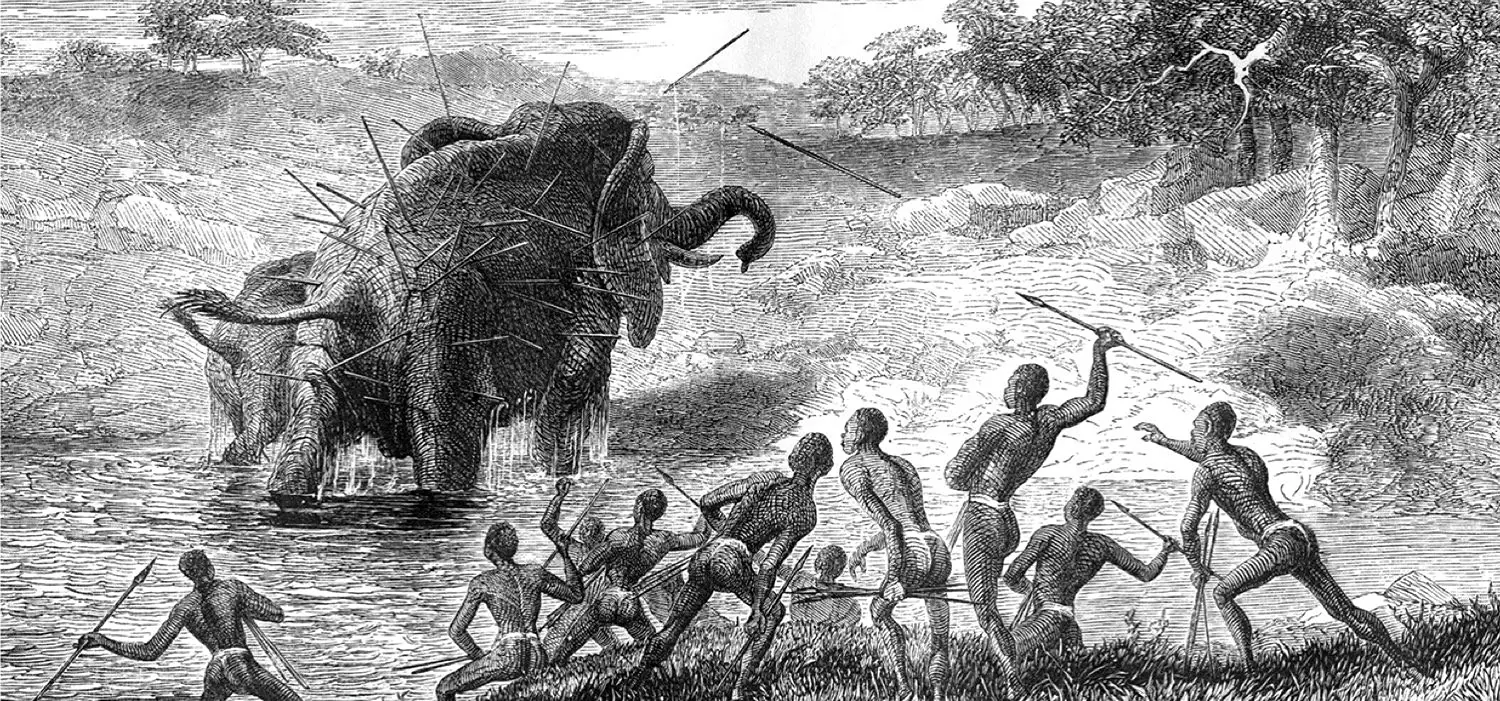

While sex and gender aren’t irrelevant in many more traditional forms of physical labor, historical accounts about the genderedness of such labor are often overstated or misleading. For instance, when prominent anthropologists (at the time, overwhelmingly male) convened at the University of Chicago in 1966 for a symposium called “Man the Hunter,” their “synthesis” of a range of biased ethnographic studies led them to conclude that intelligence itself was, literally, a product of men’s work. 24 In most traditional cultures, parties of men go out on big hunting expeditions, presumably because of their greater average size and strength. The theory held that increasingly sophisticated and cooperative hunting strategies lay at the heart of advances in technology and culture, which in turn produced an increasing surplus of high quality protein from big game, giving us more energy to grow bigger brains, and more leisure to develop better technology: a virtuous cycle.

The many problems with this “Man the Hunter” narrative have been dissected in detail elsewhere; 25 I’ll just mention a few here. In traditional societies, gathering, scavenging, gardening, and small animal hunting—all of which are more typically “women’s work”—turn out to provide more calories, more consistently, than big game hunting. Also, archeological inventories of technological development skew toward weaponry (which often features hard stone or metal points) at the expense of wooden tools, basketry, and early farming technologies, which tend to leave less physical evidence but are just as important. Finally, although cooperation was indeed central to the development of humanity as a social species, the idea that cooperation evolved from men’s activities seems dubious, given the sophistication of cooperative practices among women in traditional societies—likely beginning with cooperative child rearing. In sum, women have played a central role in the development of human civilization, but historical biases in the scholarship marginalized their role prior to a more balanced assessment of the evidence in recent decades. 26

It’s important to acknowledge, though, that men and women have meaningfully different physical capabilities, reflected in strongly gendered divisions of labor in nearly all traditional societies—whether or not this has been accompanied by patriarchy. In old fashioned, gender-binary terms: women have babies and nurse; men don’t. Men are usually more muscular than women, giving them an edge when it comes to heavy lifting. Warfare, too, is usually associated with men, perhaps not just because of physical differences, but due to testosterone-fueled aggression, a sex-linked trait found in many other animals too. 27 Women, on the other hand, are better equipped than men for endurance running, which has played a key role in some traditional societies; 28 they also tend to be healthier and, as we’ve seen, live longer.

These differences are real, and for certain kinds of physical labor, they still matter. However, in a corporate environment or on Zoom, they’re irrelevant. Desk work involves little physical exertion, which has its downsides (our bodies probably aren’t well adapted to sitting for eight hours each day), but is also equalizing. It means that physical prowess no longer confers any advantage. Today, unless you belong to a street gang, it’s either impossible or unacceptable to resolve disputes or establish hierarchies through physical combat. Sexual aggression and rape, too, are unacceptable, as is bringing any kind of sexual behavior into the workplace. The rise of remote work, the #MeToo movement, and the COVID era have all played a role in accelerating this shift, not just by reducing physical contact, but in subtler ways too—for instance, by making it impossible to tell how tall anyone is on a Zoom call. 29

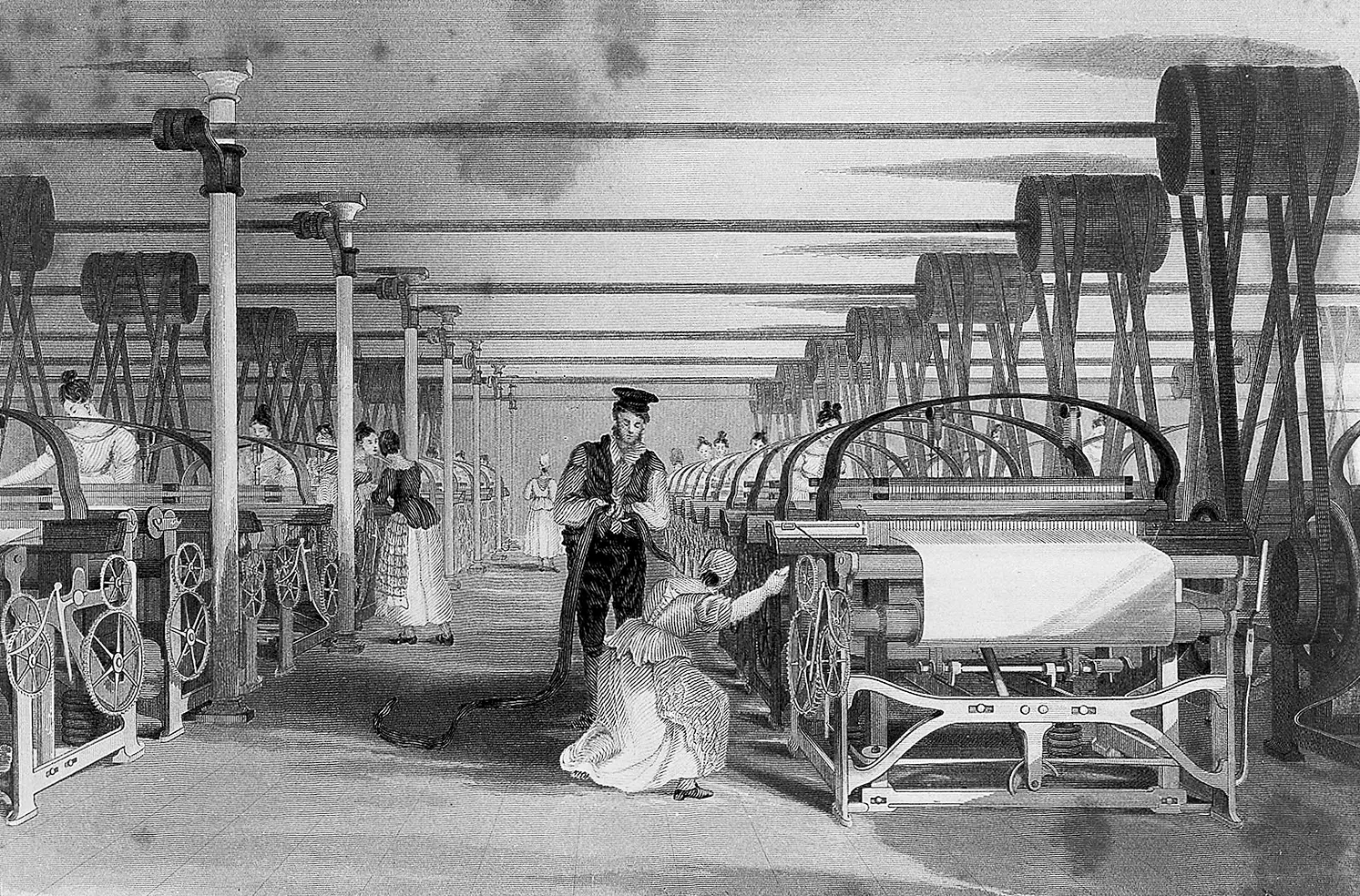

Compared to our 200,000+ year history as a species, all of these changes are very recent, and many are technologically enabled. Charles Babbage, who was not only the inventor of the computer but was obsessed with automation in all its forms, described the effect of technology on laborers in the British textile industry in his 1832 book On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures:

[From 1822 to 1832], the number of hand-looms in employment has diminished to less than one-third, whilst that of power-looms has increased to more than five times its former amount. The total number of workmen has increased about one-third; but the amount of manufactured goods (supposing each power-loom to do only the work of three hand-looms) is three and a half times as large as it was before.

In considering this increase of employment, it must be admitted, that the two thousand persons thrown out of work are not exactly of the same class as those called into employment by the power-looms. A hand-weaver must possess bodily strength, which is not essential for a person attending a power-loom; consequently, women and young persons of both sexes, from fifteen to seventeen years of age, find employment in power-loom factories. 30

In other words, industrialization—in this case, using steam to power weaving looms—turned what had been men’s work into anyone’s work. And in an era when women and children were paid far less, 31 and workers had become interchangeable, this meant women’s work and children’s work.

Nowadays, a wide array of technologies similarly decouple labor from bodies, with all their here-and-now limitations and particularities, age and sex included. Cars and trucks, motorized wheelchairs, power saws, forklifts, tractors, robotic manipulators, and many other machines extend the effect Babbage described into all areas of farming, industry, and life in general. The increasing role of military drones may even do the same for warfare. 32

While this makes many historically “male” forms of labor more accessible to women (and children, if allowed), technofeminist writers in the 1980s also wrote about many other modern developments that break the mold of traditionally “female” labor, like washing machines, showers, kitchen appliances, and vacuum cleaners. In accounts of labor-saving or -democratizing technologies we tend to forget about essential labor in the household; the subjugated status of women under patriarchy has meant that such labor has traditionally been considered a wifely duty, unpaid and taken for granted. Such domestic injustice animated the International Wages for Housework Campaign, 33 launched in 1972 by activists Mariarosa Dalla Costa, Silvia Federici, Brigitte Galtier, and Selma James—part of the larger struggle for women’s agency and economic independence touched on in Chapter 4. Although caring and caretaking remain largely uncompensated today, they’re slowly becoming less gendered, due both to changing attitudes and evolving technologies.

I remember, as a young father, changing a lot of diapers and spending many, many hours walking with a baby strapped to my chest in a BabyBjörn carrier. Back in 2002, this still attracted stares and double takes sometimes; usually delighted ones from women, occasionally uncomfortable ones from men. There’s deep muscle memory connected with that time; as I type, I find my hands, arms, and shoulders contorting to rehearse those old familiar tucking, buckling, and strap-testing gestures.

Twenty years later, carrier designs have apparently gotten a bit more ergonomic. Hundreds of baby carriers compete on the market now; Swedish BabyBjörn competitor Najell, under a photo of a hipster couple with “his and hers” twins in carriers, advertises that they’re “Designing baby carriers that fit both parents!,” adding,

Fathers are increasingly taking an equal part and responsibility in parenting and raising their children. A very positive development that we love and want to encourage. In Sweden, it’s common to share the paternity leave, often both parents take at least a few months off work to stay at home with the newest family member. […] We have designed the Najell Original Baby Carrier so there are no buckles in the back that are hard to reach. Of course, some men can be flexible, just as women can be stiff. But the fact is that most women are used to buckling bras in the back and are in general more flexible. Buckling in the back can be close to impossible for men, and there is no need for extra trouble when putting on a baby carrier. It should be easy, simple and comfortable. 34

Carriers are only the tip of an unacknowledged technological iceberg. Baby bottles, breast pumping, and refrigeration allowed my wife to leave me equipped to “nurse” our baby when she traveled for international conferences. We supplanted breast milk with formula when we needed to. Umbrella strollers let us get around the city easily, and a clever portable folding playpen let us instantly create a safe, toy-filled pop-up environment anywhere.

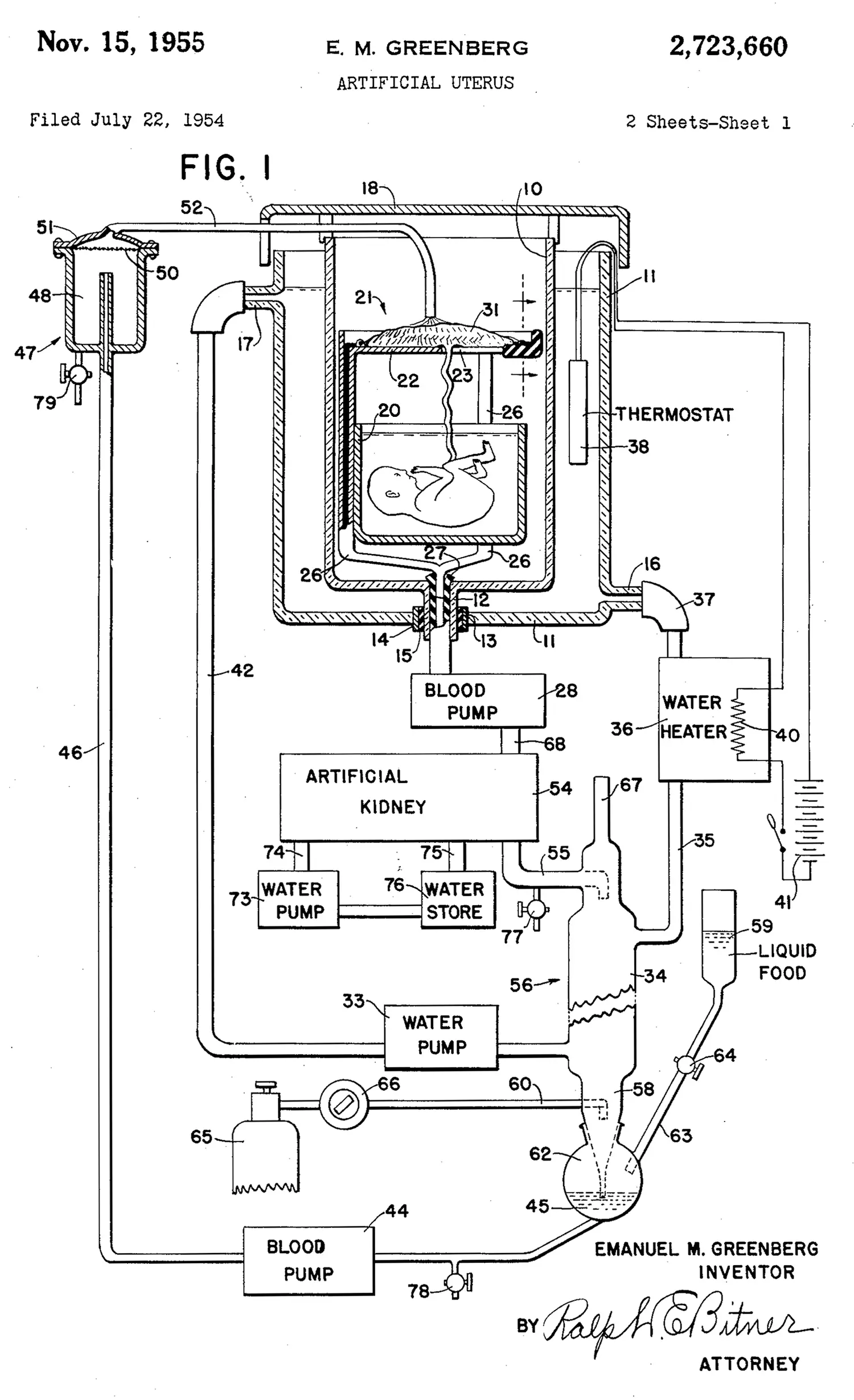

Such technologies are important but unsung, much like the wooden farming and domestic tools overlooked by so many archaeologists in the mid-20th century. The radical sex abolition politics envisioned by Shulamith Firestone in 1970 called for artificial wombs, 35 and in the coming decades we may indeed get there. 36 There’s a recent resurgence of interest in male and trans breastfeeding, a possibility available to more people than one might think—breasts aren’t nearly as sexually differentiated as genitals. 37 But it’s easy to forget how far we’ve come with much simpler social and material innovations like strollers, bottles, formula, breast pumping, unisex carriers, perinatal care, and universal parental leave. Such low-tech hacks can already bring us a fair way toward gender equality in the reproductive realm.

Of course, with biological reproduction in sharp decline, reproductive gender equality is relevant to fewer and fewer of us—a topic we’ll return to in Part III.

In many ways, our move online, in which computers increasingly mediate our every interaction with the world and with each other, continues the job of dethroning gender, turning it into an opt-in form of anonymous identity with only a tenuous connection to the shape of one’s genitals.

This is apparent in responses to the questions “Are you female?,” “Are you male?,” “Do you have a vagina?,” and “Do you have a penis?” Even among respondents who answer “yes” to only one of the first two questions, an increasing number of young people don’t answer the other two questions the way social conservatives like Matt Walsh would expect. That is, there are an increasing number of women with penises and/or without vaginas, and men with vaginas and/or without penises; these numbers follow the same pattern as “Are you trans?,” but are even higher across all ages, peaking at 4.6% among 20–23-year-olds. 38

Romantic and sexual relationships are increasingly happening online, too, potentially beginning to decouple even this intimate aspect of life from physical bodies. At the same time as it started to become commonplace to see noses and mouths disappearing behind protective masks in the “real world,” our digital faces have been undergoing a virtual makeover. Avatars, augmented reality makeup, and neural nets can re-render us completely—our gender, voice, age, race, and pretty much anything else. This puts a literal spin on N. Katherine Hayles’ claim that we’re becoming cyborgs, with our “enacted and represented bodies […] brought into conjunction through the technology that connects them.”

A split sense of self—in your own head one way, and in your presentation another—brings with it a risk of painful misalignment. Italian psychiatrist Enrico Morselli (1852–1929) first described this phenomenon as dysmorphophobia in an 1891 paper: “the sudden onset and subsequent persistence of an idea of deformity: the individual fears he has become or may become deformed (δύσμορφος) and feels tremendous anxiety (φόβος, fear) of such an awareness.” 39 Morselli believed the condition to be a common problem; he documented 78 cases.

It may not be coincidental that mirrors had only become affordable enough for the general public earlier in the 19th century, thanks to a glass silvering process invented by a German chemist in 1835. Advertising and modeling were also in rapid ascent. As people—especially girls and young women—were confronted with an onslaught of idealized female bodies in mass media throughout the 20th century, the inevitable comparison of images in the mirror with models in print and on TV (first airbrushed, then photoshopped) led to a rise in what the DSM-III-R renamed body dysmorphia, along with associated behaviors like anorexia.

With selfie filters on social media today, we’ve managed to create the perfect storm: combining the self-reflection of mirrors, the idealized (often hypersexualized) bodies of mass media, and an increasing dissociation from “meatspace.” British science communicator Liv Boeree has vividly described the ensuing phenomenon of “Snapchat dysmorphia,” 40 in which young people identify strongly with their Insta-filtered images and feel unhappy with or dissociated from their bodies. It has become a trend for young women to seek cosmetic surgery to bring their physical selves into closer alignment with their social media. 41

While accounts of “Snapchat dysmorphia” tend to emphasize hyper-feminization in young women, many other virtual body modifications are possible too. People may alter themselves to appear more masculine online, or younger. Even without explicit digital alteration, an androgynous, hoodie-wearing young person may look gender-neutral within the tightly cropped frame of a Zoom call, but less so in person. The rise in gender dysmorphia might be the tip of an iceberg. Maybe we need a proper Greek name for “online versus offline dysmorphia.”

We shouldn’t think of this phenomenon only in the negative terms of dysmorphia, though. As social creatures, our world really is each other, and in this sense, what matters to us is how we live in our own imaginations and those of others. And our imaginations are expanding. For many young people, an embrace of fluidity and rejection of either/or categories can be liberatory.

Wherever older respondents might harbor assumptions about mutually exclusive answers on the survey, growing numbers of younger respondents violate such assumptions. For instance, 2.7% of 19-year-olds identify as both or neither male and female, and more than 8% answer “yes” to more than one of the questions “Are you heterosexual?,” “Are you homosexual, gay or lesbian?” and “Are you bisexual?” When these are just social concepts, or profile settings that can be toggled on a dating or social media app, there’s no need to box yourself in. Our inherent flexibility finally has free rein.

How far will the cyborg-like digital dissociation between bodies and identities go? At this point, it’s unclear. Neural nets can transform our digital selves in any conceivable way—far beyond anything surgery can approximate. New deepfake-like techniques aren’t limited, the way Photoshop was in the old days, to smoothing a bit here or slimming a bit there. The language we’re speaking can be altered, we can become skilled singers, we can be rendered as cartoons, we can look like elves or pixies. Or even nonhuman entities.

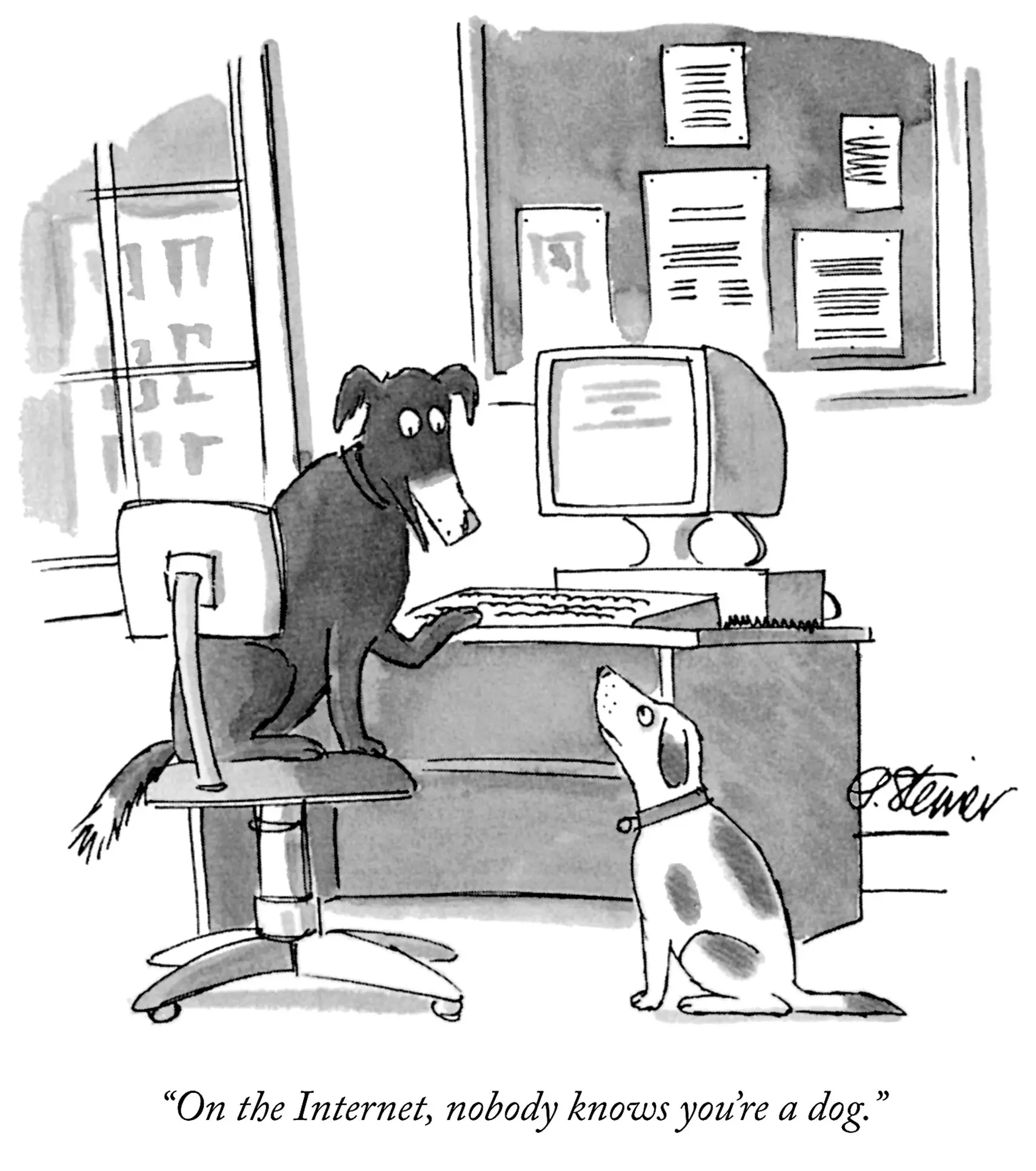

The old adage, “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog” was coined by New Yorker cartoonist Peter Steiner in 1993, in an era when social interaction online consisted of a handful of nerds at universities typing text into chat windows. Online culture has come a long way in the three decades since. While the actual “internet of animals” 42 still hasn’t taken off, it’s now commonplace for humans to present as other species online—though cats are more popular than dogs. It’s also becoming increasingly difficult to tell humans from AIs. Online, Daphna Joel’s vision of “gender abolition” seems almost quaint in restricting itself to that one old-fashioned variable.

In Chapter 4, I cited science fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson’s visionary novel 2312, which describes a distant future in which we acquire a degree of control over our bodies that renders us posthuman. I added that even Robinson’s vision was conservative compared to the “uploading” scenario, in which we become virtual beings unconstrained by bodies altogether. Yet this is exactly what we’re already doing digitally, without any of the fuss, downtime, commitment, risk, and expense of surgery, hormones, or gene splicing. Even clothes shopping, haircuts, and grooming become optional when equivalent (or better) effects can be applied directly to pixels.

Is this just a superficial fad, or is it something more profound? It really depends on which we consider the real world—the flesh and blood one, or the one we’re creating for ourselves online. Of course the virtual world depends on the physical world to exist, but then again, the Earth depends on the sun, and the city on the countryside. The question is: where do we live? That is, who are we now?

The answer varies—partly, by age. Some of us are in constant contact with the physical, still making a living by pushing brooms, nursing or caretaking, pulling shots of espresso, picking fruit or painting houses; still spending our time with clients, coworkers, friends, and lovers in the flesh. For others, reality is online. As always, there’s no binary; most of us are dual citizens. But if we’re honest with ourselves, especially since COVID, many of us have been online more than not. Does this mean we’ve already been uploaded… without even noticing?

Bechtel, “Don’t do this, @Target,” 2015.

ABC News, “Target Moves Toward Gender-Neutral Store Signage,” 2015; Suhay, “Target Experiments with Gender Neutrality in Its Stores,” 2016; Lang, “Target to Install Gender-Neutral Bathrooms in All of Its Stores,” 2016.

Miller, “Target Debuts An All-Gender Product Line For Kids,” 2017.

Walsh, “Yes, Target, I Do Want My Daughter to Conform to Her Gender,” 2015.

Among the larger studies with statistically meaningful datasets are Ruigrok et al., “A Meta-Analysis of Sex Differences in Human Brain Structure,” 2014; Ritchie et al., “Sex Differences in the Adult Human Brain: Evidence from 5216 UK Biobank Participants,” 2018.

Joel and Vikhanski, Gender Mosaic: Beyond the Myth of the Male and Female Brain, 2019.

Joel’s work implies that the distribution of values for each individual brain measurement is, in the previous chapter’s vocabulary, dromedary-like, or one-humped, like the distribution in body height. It still may be the case, however, that a predictor combining many individually unreliable measurements together would yield a more distinctly two-humped distribution.

These numbers are changing. In some scientific fields, women now outnumber men. Language tends to be a lagging indicator, though.

As with handedness (see Chapter 3), etymology tells this story: “woman” derives from the Old English wīfmann, a compound of wīf, meaning female—whence “wife” in modern English—and mann, meaning person or human being—whence “man” in modern English. Hence a woman is a female man (marked), while a man is just a mann (unmarked).

Serano, Excluded: Making Feminist and Queer Movements More Inclusive, 2013.

The irrelevance of such physical features doesn’t stop science journalists from habitually playing physiognomist, as in, “The distinguished old scientist has a shock of white hair, and a protruding, yet somehow also majestic, pair of ears.”

Goldenberg, “Why Women Are Poor at Science, by Harvard President,” 2005.

The memo got Damore fired: Damore, “Google’s Ideological Echo Chamber: How Bias Clouds Our Thinking About Diversity and Inclusion,” 2017.

Sadly, neither lived to see such a machine built, let alone a program run.

Hollings, Martin, and Rice, “The Lovelace–De Morgan Mathematical Correspondence: A Critical Re-Appraisal,” 2017.

Lombroso and Ferrero, La donna delinquente, la prostituta, e la donna normale, 1893.

Quotes are from the translation by Nicole Hahn Rafter and Mary Gibson of Lombroso and Ferrero, Criminal Woman, the Prostitute, and the Normal Woman, 2004.

“Why can’t a woman be more like a man?,” Cukor, My Fair Lady, 1964.

See Chapter 11.

Goldin and Rouse, “Orchestrating Impartiality: The Impact of ‘Blind’ Auditions on Female Musicians,” 2000.

Tommasini, “To Make Orchestras More Diverse, End Blind Auditions,” 2020.

Think of GitHub as a social media platform, except that every post consists of a chunk of code contributed to one of the more than 100 million software projects hosted there, rather than a drunk selfie you’ll regret tomorrow morning. GitHub-hosted software powers much of our digital lives.

Murphy-Hill et al., “The Pushback Effects of Race, Ethnicity, Gender, and Age in Code Review,” 2022.

Lee and DeVore, Man the Hunter: The First Intensive Survey of a Single, Crucial Stage of Human Development—Man’s Once Universal Hunting Way of Life, 1968.

Sterling, “Man the Hunter, Woman the Gatherer? The Impact of Gender Studies on Hunter-Gatherer Research (A Retrospective),” 2014; Gurven and Hill, “Why Do Men Hunt? A Reevaluation of ‘Man the Hunter’ and the Sexual Division of Labor,” 2009; Haas et al., “Female Hunters of the Early Americas,” 2020.

In the 1960s, as for orchestras, the overwhelming majority of anthropologists were male. There are now two female PhD graduates in anthropology for every male, and the majority of faculty hires in anthropology are women. Speakman et al., “Market Share and Recent Hiring Trends in Anthropology Faculty Positions,” 2018.

Mazur and Booth, “Testosterone and Dominance in Men,” 1998; Muñoz-Reyes et al., “The Male Warrior Hypothesis: Testosterone-Related Cooperation and Aggression in the Context of Intergroup Conflict,” 2020.

Tiller et al., “Do Sex Differences in Physiology Confer a Female Advantage in Ultra-Endurance Sport?,” 2021; Lieberman et al., “Running in Tarahumara (Rarámuri) Culture: Persistence Hunting, Footracing, Dancing, Work, and the Fallacy of the Athletic Savage,” 2020.

I’m about 6’ tall, which, in ordinary life, is on the taller side. When I first attended the TED conference and found myself surrounded by CEOs and other high-status people, I was struck by a sense of suddenly being shorter than everyone (with the exception of Jeff Bezos). A number of studies have confirmed a powerful height bias, especially among men, in the corporate world. Judge and Cable, “The Effect of Physical Height on Workplace Success and Income: Preliminary Test of a Theoretical Model,” 2004.

Babbage, On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures, 339, 1832.

For instance, in writing about pin manufacturing, Babbage writes, “It is usual for a man, his wife, and a child, to join in performing these processes; and they are paid at the rate of five farthings per pound. They can point from thirty-four to thirty-six and a half pounds per day, and gain from 6s. 6d. to 7s., which may be apportioned thus; 5s. 6d. the man. 1s. the woman, 6d. to the boy or girl.” If you’re unfamiliar with old British money, this works out to 66 pence for the man, 12 pence for the woman, and 6 pence for the child for a full day of labor. Child labor nowadays is largely illegal, and this kind of pay discrepancy gives us a sense of what the gender pay gap statistics in Chapter 4 looked like farther back.

Westerman, “Ukrainian Women Have Started Learning a Crucial War Skill: How to Fly a Drone,” 2022.

Federici, Wages Against Housework, 1975.

Najell, “Designing Baby Carriers That Fit Both Parents!,” 2021.

The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution, chap. 10, 1970.

Usuda et al., “Successful Use of an Artificial Placenta to Support Extremely Preterm Ovine Fetuses at the Border of Viability,” 2019.

Cederstrom, “Are We Ready for the Breastfeeding Father?,” 2019; Wamboldt, Shuster, and Sidhu, “Lactation Induction in a Transgender Woman Wanting to Breastfeed: Case Report,” 2021.

Per Chapter 13, this also speaks to the way increasing numbers of trans people, especially among the young, don’t see being trans as implying or requiring medical treatment.

Morselli, “Sulla Dismorfofobia E Sulla Tafefobia,” 1891. See also Fava, “Morselli’s Legacy: Dysmorphophobia,” 1992.

Boeree, “In my experience, all the furore over Instagram & Facebook causing teenage depression is overlooking the bigger issue: beauty filters. I mean just look at this absurdity,” 2021.

Walker et al., “Effects of Social Media Use on Desire for Cosmetic Surgery Among Young Women,” 2021.

Curry, “The Internet of Animals That Could Help to Save Vanishing Wildlife,” 2018.