Ours is a world in vertigo. […] We are all alienated—but have we ever been otherwise? It is through, and not despite, our alienated condition that we can free ourselves […] nothing is so sacred that it cannot be reengineered and transformed so as to widen our aperture of freedom, extending to gender and the human. To say that nothing is sacred, that nothing is transcendent or protected from the will to know, to tinker and to hack, is to say that nothing is supernatural.

Laboria Cuboniks, Xenofeminist Manifesto, 2018

You will find your answers in the secrets of strangers.

Frank Warren, creator of Postsecret, 2004

An anonymous caller’s voice played over the laptop’s speakers. “Hi, Dan. This is a 26-year-old bisexual man in New York, and I have a somewhat strange question. Watching the HBO show Westworld, I’ve been thinking… if there were hyper-advanced sex robots and you were to have sex with one, would that be cheating? I mean, isn’t it just like a really fancy sex toy? Or is there some other component, like, if you had an emotional connection that means something else. I don’t know. What do you think?”

The recording clicked off. Dan Savage, looking both mischievous and a bit world-weary, waited a beat, then leaned into his microphone and spoke. “Joining me in our studio today to help tackle this very important question about robots, Westworld, and AI is Blaise Agüera y Arcas, who is the head of Google’s machine intelligence effort here in Seattle.”

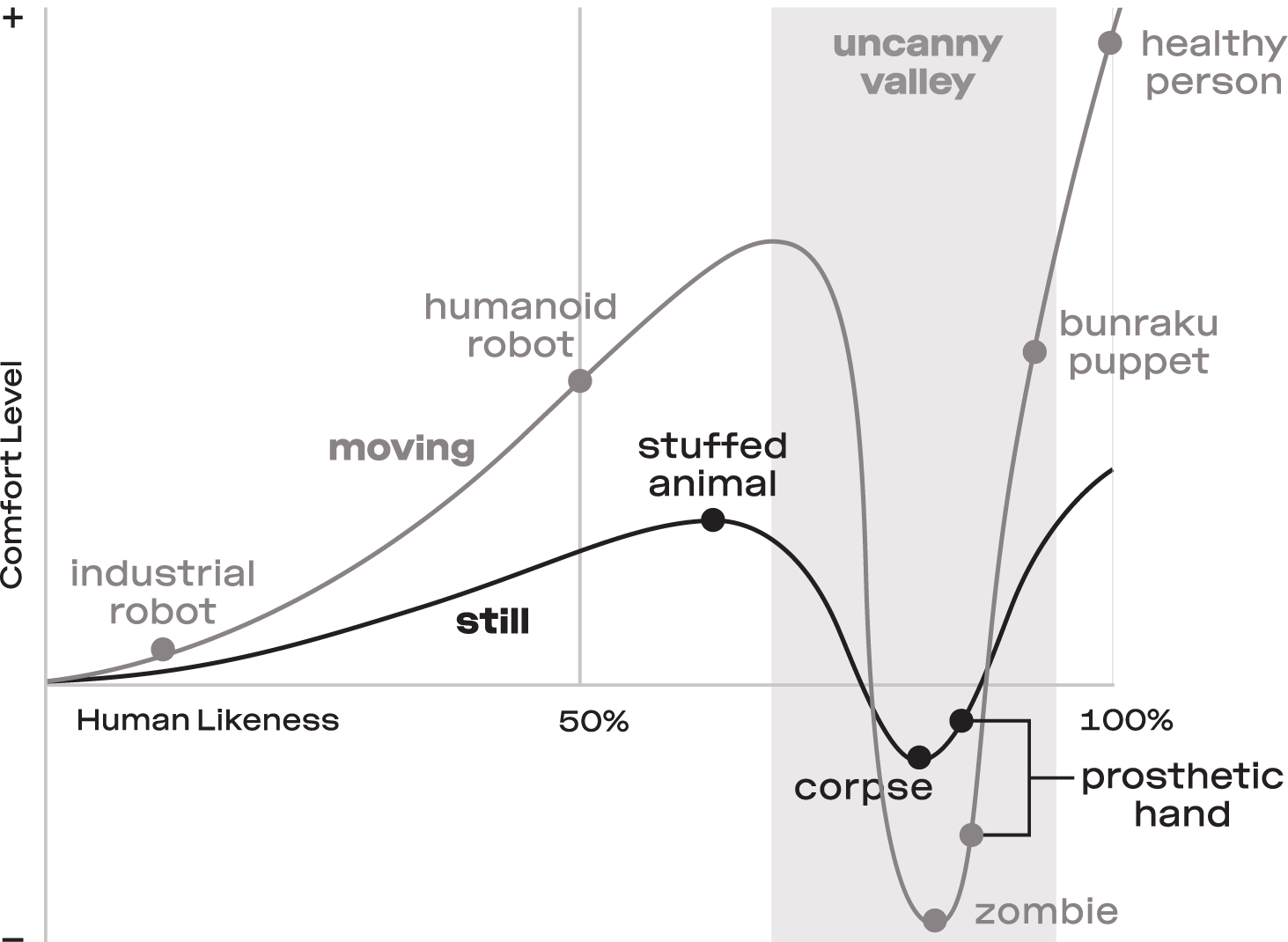

Cutting politely through my equivocations, Dan took this one into his more capable hands—“It’s cheating if your partner thinks it’s cheating, period, the end”—then shifted the conversation into territory I’m slightly more qualified to have opinions on: the state of machine learning today, the way we project personhood onto inanimate things, and what the Turing test might look like—in bed. Bad puns about uncanny valleys were made.

(In case you’re not familiar with it: the Turing test, which will come up again in Chapter 14, was a thought experiment proposed by computing pioneer Alan Turing in 1950. He pointed out that, since we have no objective way of determining when a machine goes from being an “it” to a “who,” we may as well simply ask it to convince us that it can stand in for a human in an online chat. As for the “uncanny valley,” the phrase was invented by Japanese robotics professor Masahiro Mori in 1970 to refer to that in-between situation in which something humanoid is just realistic enough to be creepy—without being realistic enough to be convincing. The characters in the 2004 animated movie The Polar Express are an oft-cited example.)

As I gamely struggled to answer Dan’s rapid-fire followup questions (“Do you guys talk about how everyone’s going to be fucking what you’re working on?”), I remember hoping I wouldn’t get in too much trouble with my employer when this episode of the Savage Lovecast aired. 1 Sometime after we’d wandered off into the thickets of whether consciousness is an illusion, and when people with Avatar kinks would get their very own giant blue sexbots, Nancy Hartunian, the Lovecast’s long-suffering producer, rolled her eyes and signaled for us to wrap it up.

The recording stopped, but conversation continued. The ethical conundrum of how advanced a sex toy needs to be before we start having to ask for its consent was a welcome distraction, but I didn’t really have robots, sexy or otherwise, on my mind that day. I was thinking about people. How were they voting? It was Election Day: Tuesday, November 8th, 2016. It was hard to think of anything else.

Dan, normally a worrywart, was uncharacteristically confident that Hillary had it in the bag. So was everyone else in Seattle, a famously/notoriously progressive little blue dot near the upper left corner of the US map. Despite an unspoken agreement not to jinx it, the mood was expectant, even festive. Parties were being planned for the evening, including one at my place. Champagne was chilling in the fridge. Nancy and her family would be dropping by.

I was less certain. I’d been checking Nate Silver’s FiveThirtyEight polling website obsessively, and while it, too, favored Hillary, her lead was far from decisive. Everyone seemed to be ignoring the margin of error… and it was substantial.

Although not on the same scale as all of those big national polls, my own data had me wondering, too. As a side project, I’d been running surveys using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform, which lets you code up questionnaires and crowdsource responses from people all over the country. Having learned about Mechanical Turk as a frequently used tool for generating AI training data, I wanted to use it to satisfy my curiosity instead. At first, my questions were straightforward. They ran along the lines of: Who will you vote for? What issues do you care about? What do you believe? Who are you?

I didn’t want to be exploitative, so I was paying my respondents decently—and this was turning into an expensive hobby. Still, it was cheap and easy compared to the phone banking or field operation needed to run such a survey a few years ago. Now it could all be done from a laptop, and with a turnaround time of mere hours. I felt like I was learning a lot about my fellow human beings. Every insight suggested more questions I wanted to ask, hence a new survey, more graphs, more analysis. It was addictive.

As soon as I’d begun these experiments, in the summer of 2016, it had become clear that the way people would vote had less to do with policy positions than with identity; “Who are you?” turned out to be the key. It was about “us” versus “them.” Granted, it’s no news that tribalism is a part of human nature, but it seemed like an especially powerful driver during this election cycle. Much of Donald Trump’s brand was based on the idea of building a wall to protect “us” from “them,” and it had become increasingly clear that “they” included not only undocumented border crossers, but minorities of all kinds within the United States. “They” included immigrants, people of color, LGBTQ+ people, academics, people who aren’t Christian. At times, women seemed to be included too, and anybody with a disability, and everybody living in the city. 2 Of course the resulting “majority” then turns out to be a minority—but one that held the reins of economic and political power last century, during the half-real, half-mythical era people had in mind when they chanted “Make America Great Again!”

In response to the free text question I had begun adding to my surveys (“Is there anything you’d like to add?”), I had seen comments like:

I believe that as a society we have moved in a positive direction regarding inclusion in recent years and this will only benefit everyone in the long run. 3

On the other hand, I had also seen:

I am an Anglo Saxon European American male. The most hated discriminated group in America. I am looking forward to the civil war. Oh, and not the Anglo Saxon side which conspired with these Jews to rip Americans off. I am from the side that didn’t get paid. 4

Beyond the numbers, responses like these were going through my head as I confessed to a skeptical Dan and Nancy in the podcast studio that I thought Trump might win. We’d been debating whether we’d need to empathize with machines in the future, but in the meantime we humans weren’t even managing to acknowledge each other.

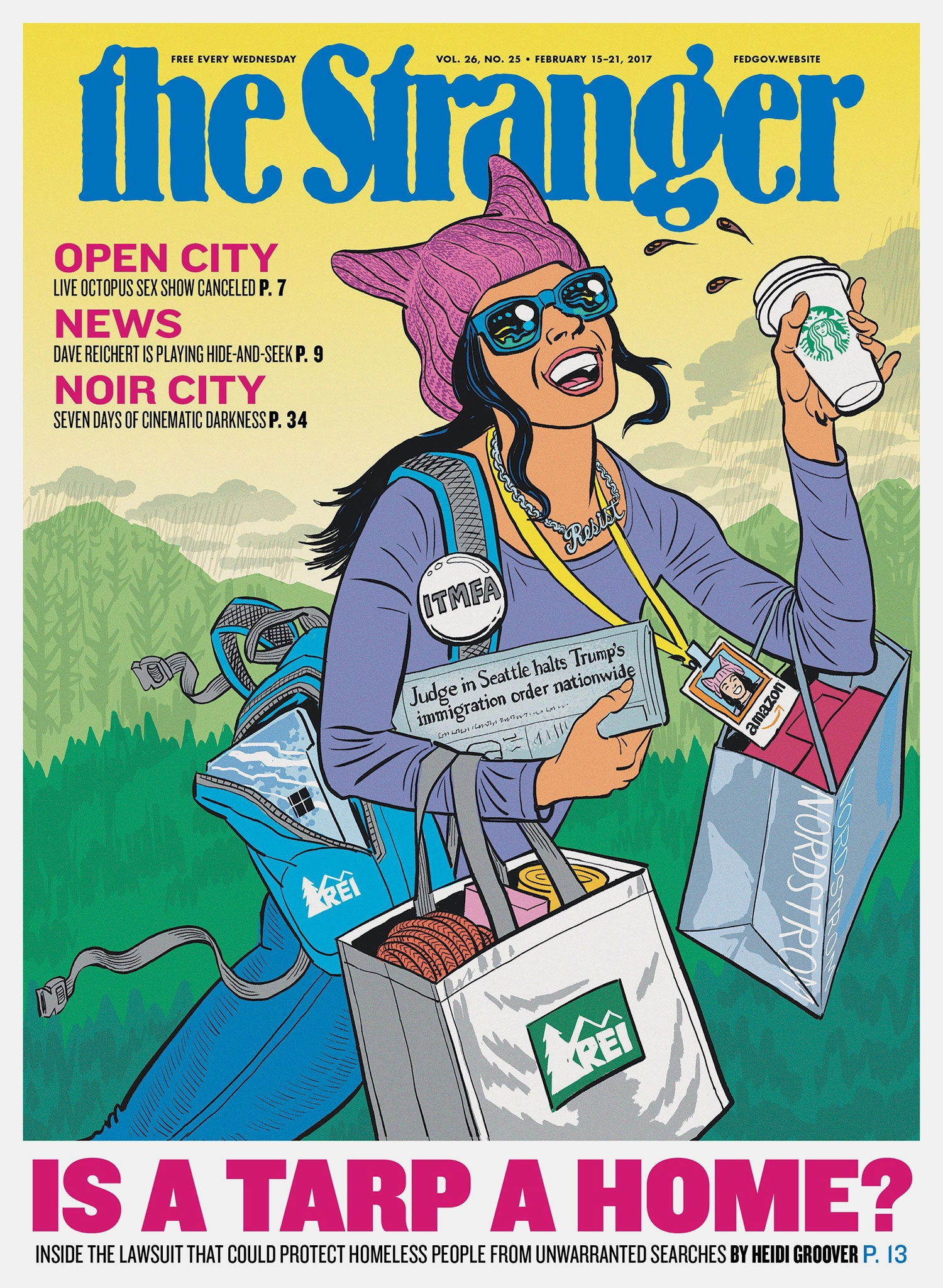

The Stranger, Seattle’s alt-weekly newspaper, has been home to Dan’s sex advice column, Savage Love, since its first issue in 1991. Nancy had cajoled him into podcasting when that medium was still new, in 2006. The Stranger’s smart, cheeky, lefty, and often smutty sensibility feels much like the voice of the city itself; it’s much like the voice of many US cities. In places like Seattle, sentiments like those of my Anglo Saxon European American respondent could seem distant and irrelevant. But my statistics told me that he was far from alone.

I was thinking about him as I unlocked my bike in front of the Stranger’s offices, on a street that would briefly become, four years later, part of the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone. The call for civil war was still in my head when, a few hours later, my family and friends huddled around the kitchen table, listening soberly to the returns coming in from one swing state after another, our drinks untouched.

“Who are these people?” someone asked quietly.

This question presupposes something profound about what it means to be human—something far deeper and more enduring than election cycles, political parties, nationalities, religions, or robot kink communities.

It’s a remarkable intellectual achievement to be able to respond to questions about who you are. To understand why, consider first the language needed to make such questions precise. “Did you vote for Jill Stein?” and “Do you use the men’s bathroom?” are straightforward enough, but what about “Do you identify as liberal?” or “Are you bisexual?” The last two questions are about identity, not about behavior. To understand why the difference matters, let’s imagine what life was like for our pre-human ancestors, and what it’s still like for our nonhuman cousins.

If you were, for instance, a chimpanzee, you would be able to communicate, and even, to a degree, use language. However, questions about identity likely wouldn’t make any sense to you, because as a chimp you’d lack the ability to “identify” in any collective way—what I’ll call having an “anonymous identity.”

You wouldn’t lack an individual identity, or meaningful relationships with others. I’m pretty sure you would feel like a person, and would understand that other people have their own experiences, just as you do. It’s hard to imagine otherwise, after spending some time watching old documentary footage of the groundbreaking primatologist Jane Goodall interacting with the chimps in Tanzania’s Gombe National Park. As a chimp, you’d have a rich inner life, experiencing much the same range of emotions humans do. You’d love, quarrel, scheme, form alliances, and problem solve. When Frans de Waal, another prominent primatologist, wrote the bestselling Chimpanzee Politics in 1982, 5 the shenanigans described were so instantly familiar to US Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich that he put it on a recommended reading list for his colleagues in Congress. 6

Not that any of these behaviors are unique to higher primates. If you have a cat, dog, or parrot at home, you probably feel that much of this holds for your nonhuman friend too. We’re animals ourselves, and in almost every respect we’re much like the other big-brained creatures we share our planet with.

However, two important characteristics make humans unusual. One is complex language, and the other, which is closely related, is our ability to identify collectively to form large “anonymous societies.” 7

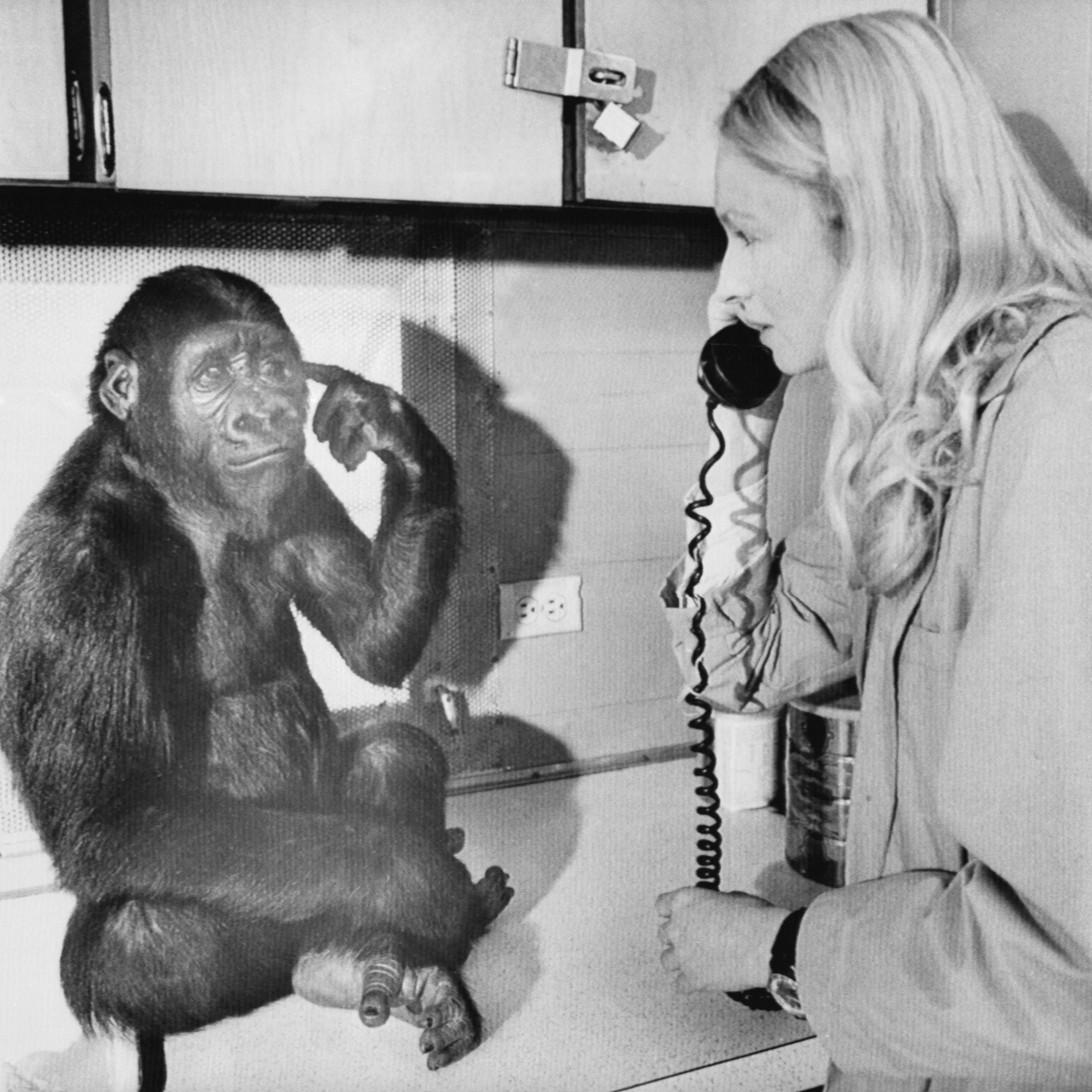

We all know what language is, though it’s not accurate to claim that complex forms of communication are uniquely human. There are unanswered questions about advanced communication among whales and dolphins, for example; chimps and gorillas can be taught elements of sign language; and prairie dogs, amazingly, can warn each other about the color and shape of an invader. 8 Parrots can even learn our spoken languages, albeit not with adult human proficiency. Researchers and animals who have established true symbolic interspecies communication—like Koko the gorilla with Francine Patterson, or Alex the parrot 9 with Irene Pepperberg—should convince us that humans don’t hold a copyright on speech.

However, these rare connections also highlight a gulf in depth and degree. Humans have a talent for language that’s probably unparalleled on Earth, and has been key to developing the cooperative strategies, technologies, and cultures that, over the course of many generations, have turned us from a niche species into a world-shaping force.

Symbols are at the heart of language. These are abstractions that “digitize” the analog world around us, turning a welter of continuous perceptual impressions into discrete entities with names: fruit, tree, rock, chimp. Recognizing individual people and assigning them names—like “Alex” or “Irene”—is an especially important case. We have every reason to believe that many animals with big brains have individual recognition, and some can even use names. (In 1983, for example, Koko the gorilla asked for a cat for Christmas, and was eventually allowed to choose a kitten from an abandoned litter. She named him “All Ball,” and loved him.) In a primate troop, everyone recognizes everyone else individually. However, there’s no evidence that nonhuman primates have anonymous societies, the way humans do.

In an anonymous society, people aren’t (or aren’t only) identified by their individual names, but by symbolic markers of group identity, such as race, nationality, tribe, class, sexuality, profession, membership in a club or guild, political party, and so on. I call these associations “anonymous identities”—a seemingly paradoxical phrase, but an apt one, since when we say that a person “identifies” as, for example, “a Christian Gen Xer,” they have both identified themselves and remained anonymous.

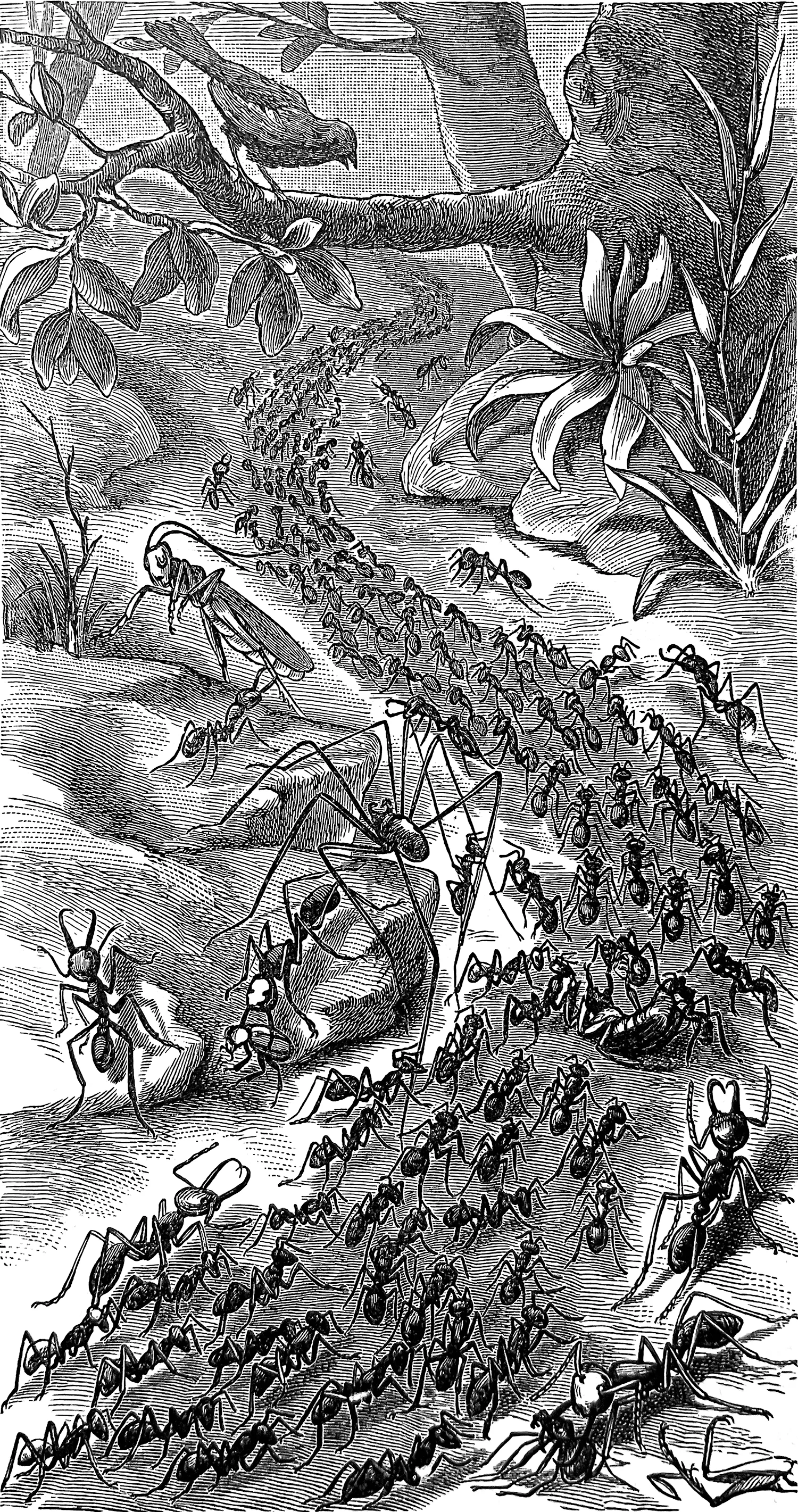

Curiously, we find anonymous societies mostly in animals with tiny brains, like ants and bees. In the distant past, these insects roamed individually or in small groups, but eventually, many different lineages independently evolved the same highly beneficial trait: collective identity. Ants, for instance, can live in a colony with a large number of individuals, cooperating closely within the colony—while being at war with ants in other colonies. They distinguish “us” from “them” using pheromones. There’s really no other way to do it, since their numbers are so large (and their brains are so small) that it would be impossible to distinguish “us” from “them” using individual recognition. So instead, they use the chemical equivalent of team jerseys.

In this important respect, humans are more like social insects than like other primates. Psychologist Jonathan Haidt had a similar idea in mind when he called us “90 percent chimp and 10 percent bee.” A chimp colony could never grow to the size of an ant colony or beehive—let alone a human city—because chimps rely on individual recognition.

Relationships based on individual recognition can still result in something like in- and out-groups. When Jane Goodall and her colleagues observed a troop of chimpanzees they referred to as the “Kasakela community” undergo a violent splintering into two communities, afterward referred to as the “Kasakela” and the “Kahama,” they may have been mistakenly projecting a human idea onto a nonhuman situation. Consider Frans de Waal’s description of this “Gombe Chimpanzee War,” written 30 years later:

[C]himpanzees [that] had played and groomed together, reconciled after squabbles, shared meat, and lived in harmony […] began to fight nonetheless. Shocked researchers watched as former friends now drank each other’s blood […] us-versus-them among chimpanzees is a socially constructed distinction in which even well-known individuals can become enemies if they happen to hang out with the wrong crowd or live in the wrong area. In humans, ethnic groups that used to get along reasonably well may all of a sudden turn against each other, as the Hutus and Tutsis did in Rwanda and the Serbs, Croats, and Muslims in Bosnia. What kind of mental switch is flipped that changes people’s attitudes? And what kind of switch turns chimpanzee group mates into each other’s deadliest foes? I suspect the switches operate similarly in humans and apes […]. 10

De Waal has written a number of books about how the behavior of other primates offers profound insight into human behavior, but here, he may be making an unwarranted leap. Chimps aren’t friendly to other chimps by default. They distrust strangers, but may over time develop a bond, or at least a relationship with established parameters (with one dominant over the other, for example). These dynamics, together with the bonds that arise from mating and child-rearing, naturally lead to evolving clusters of individuals that are comfortable—or comfortable enough—being near each other. Scientists who study animal behavior use the term “fission-fusion societies” to characterize the result. The clusters are more or less stable, but can change either over the course of a day (for example, as foraging parties go out in the morning but reconvene at night) or over longer periods of time (as when a few individuals decide to strike out on their own, or, with careful deference, join an existing group).

A human observer might identify a cluster of chimps who get along as a community, and give it a name. However, from the inside, there’s no evidence that collective identity exists; no community name, tribal flag, or team jersey. Upon re-analyzing Jane Goodall’s field notes, social scientist Joseph Feldblum noted that the split seemed to have been precipitated by the death in 1970 of a single senior male, Leakey, who “seems to have been a bridge between the northern and southern chimps.” 11 What looks from the outside like one community splintering into two factions might feel, from the inside, like a web of relationships that has frayed, in which friendships don’t have enough force to overcome enmities, and in which individuals who no longer hang out together become estranged over time. We might still say that troops or colonies “exist” as a phenomenon we can observe, in the same way that clouds or patches of clover exist, but they may not correspond to a concept in the minds of the chimps themselves.

As far as we know, chimps don’t explicitly identify with communities. Nor do any other primates, aside from us. Hence, events like the Gombe Chimpanzee War can only occur locally, on a scale of dozens of individuals, unlike the “mental switch” that flipped between the Tutsis and the Hutus, or between the Serbs, Croats, and Muslims, both of which led to genocide.

One could argue that community is just as fundamental to humanity as language. This isn’t just for the reasons everyone talks about—because we need friendship, love, and emotional support; chimps need and have those relationships too. It’s because, as the last section of this book will explore, the development of culture and technology requires the concentrated interaction of many people. Language is how those interactions take place; community is with whom.

-Enhanced-EDIT.webp)

Community size matters. Throughout our history, wherever the number and density of interacting humans is very low, we not only find that technologies and cultures develop more slowly, but that they can regress. The isolated Tasmanian people, for example, forgot over the generations how to fish and make many of the tools their ancestors on the Australian mainland used. 12 By the 19th century, the Andamanese, inhabitants of an island archipelago in the Indian Ocean, had forgotten how to make fire. As far as we understand, they continually tended lit embers in hollowed-out trees, and would need to rely on “harvesting” wildfire from a lightning strike if those embers were to go out. 13 They didn’t end up in this situation because they’re any less intelligent than anyone else. It happened because knowledge, like those glowing embers, must be nurtured and passed down from generation to generation. With too few people, the risk of loss with every generation comes down to a roll of the dice.

It follows that the answer to the question “How many humans does it take to screw in a lightbulb?” is probably a few million, given the complexities of mastering electricity and industrial manufacturing. Yet we can’t achieve the critical mass needed for evolving this kind of advanced technology without anonymous societies to allow for large, stable communities.

When we consider that no vertebrate on Earth other than us has societies larger than 200 individuals or so, 14 we should wonder whether our individual intelligence is really humanity’s special sauce. To an alien visiting the Earth 100,000 years ago, small bands of human hunter-gatherer-scavengers might not have stood out relative to the planet’s other large-ish fauna.

On the other hand, we’re animals that talk. While nobody knows for sure how anonymous human societies first arose, my guess is that they’ve been with us for a very long time—specifically, since language itself arose. If there ever was a Tower of Babel time in which we all spoke the same language (unlikely), it wouldn’t have taken long for this one language to splinter into many. Over generations, language evolution produces linguistically differentiated populations in much the way genetic evolution produces new species. Language, culture, and group identity would have co-evolved and reinforced one another, creating rifts in the process. Everyone would have become aware of an “us” (people who speak the same language) and a “them” (people who don’t). 15

The latter would often have been further divided into those speaking different recognizable but incomprehensible foreign languages. Hence, the names of many of today’s most popular languages are also the names of the people who first spoke them: French, Vietnamese, English, and so on. That these terms also correspond to the names of countries defined by clearly delineated polygons on the world map is a more recent development.

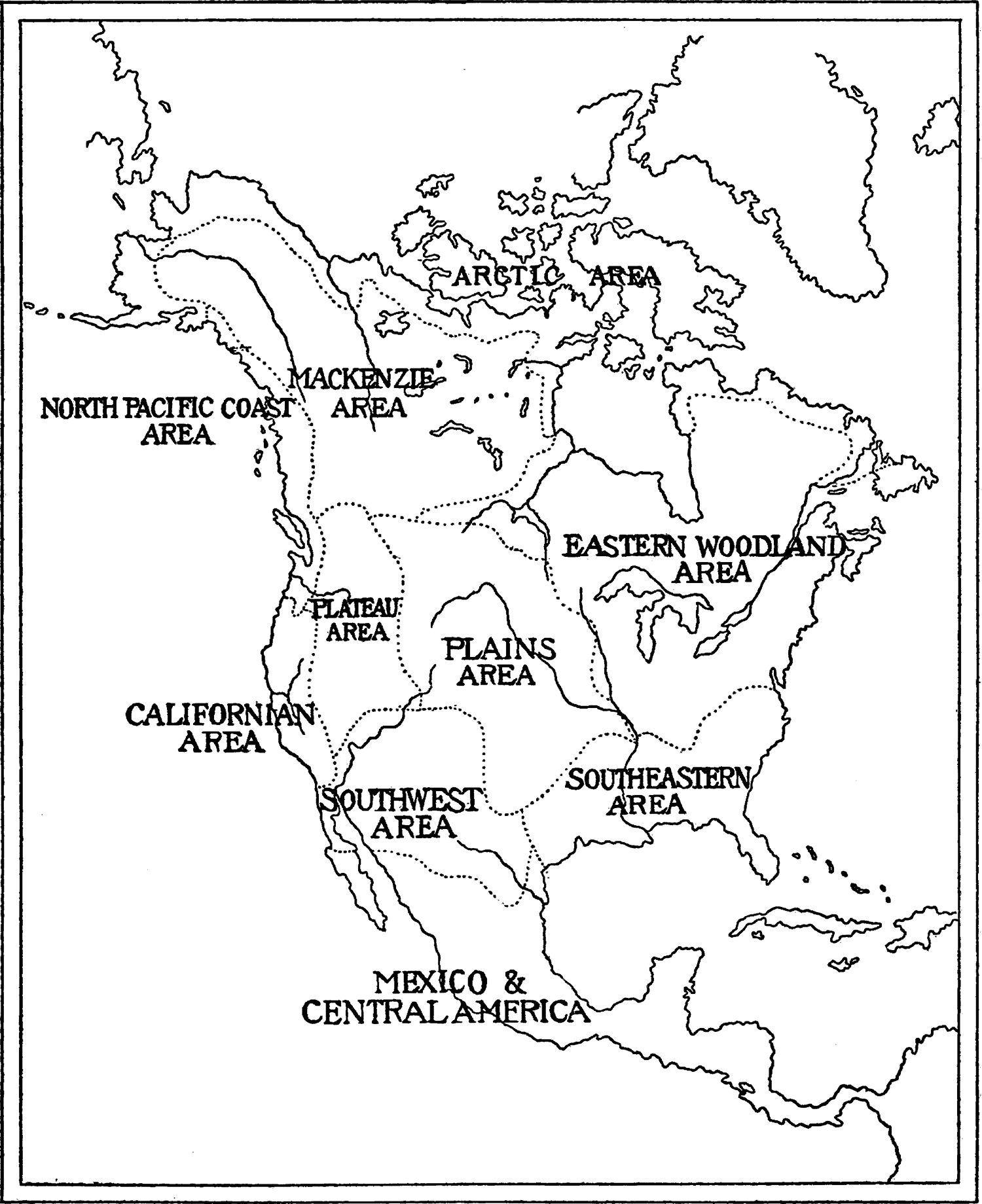

Native North American tribes offer a catalog of evidence about how such names generally work. For instance, Kwakwaka’wakw (the tribe commonly known today as Kwakiutl), means “speakers of our language”; “Cherokee” or “Tsalagi” derives from a Muskogee word for “speakers of another language.”

The word for “person” or “people” in a tribe’s language has itself often turned into the name of the people who speak that language. For instance, Dena’ina, Dene, Dine’e, Gwich’in, Innu, Inuit, Iyiniwok, Lenape, L’nu’k, Maklak, Mamaceqtaw, Ndee, Numakiki, Numinu, Nuutsiu, Olekwo’l, and Tsitsistas are all tribes whose names simply mean “people” or “the people.” So, ironically, the one word that ought to encompass everyone—“people”—spoken in many languages immediately implies many distinct tribes. Moreover, it suggests the ultimate “othering”: that foreigners aren’t even people.

Unlike species membership, though, belonging to one language group does not preclude membership in another. Multilingualism means that certain people, in any era, belong to multiple linguistic groups, literally able to “code switch” between accents, dialects, or languages. During the long stretches of prehistory when people spent their lives roaming over vast distances, this undoubtedly eased cooperation, trade, and knowledge exchange, and may have been key to allowing practices and technologies to diffuse over “culture areas” spanning whole continents. 16

Over the last 10,000 or so years, though, certain populations became increasingly dependent on farming and the year-round settled lifestyle that implied. Such conditions would have caused anonymous identities to further crystallize. Regardless of ideas about property and ownership (it was often collective), individuals would have begun to think of themselves as tied to permanent dwellings, and to the surrounding cultivated land. Hence place names became common symbolic markers of anonymous societies.

Farming could support larger concentrations of people in one place—more than could have known each other personally. A shared anonymous identity would have been at least as important a “technology” as farming itself to allow for the cohesion of large communities with common norms, customs, and laws. 17 Settled societies also gave rise to increasingly fine-grained division of labor, which would have produced yet more anonymous identities—of the kind eventually institutionalized into so-called “voluntary associations” like guilds, councils, and clubs. Finally, farming would have allowed (or required) big extended families to grow in place over many generations without the continual fission and fusion that characterizes a more mobile lifestyle. This is presumably how clans arose.

Thus, compound names today often comprise an “individual symbol” (first or given name) and a “team symbol” (family, clan, or surname) based on one of the following properties: place (as in Jack London), profession (as in Anita Baker), and ancestor (as in Sinéad O’Connor). Notice that anonymous identities almost from the start would have been multiple: an individual would have identified in all of these overlapping ways at once. An ancestral O’Connor might not only have been a member of the O’Connor clan, but also a blacksmith, and a resident of Dublin.

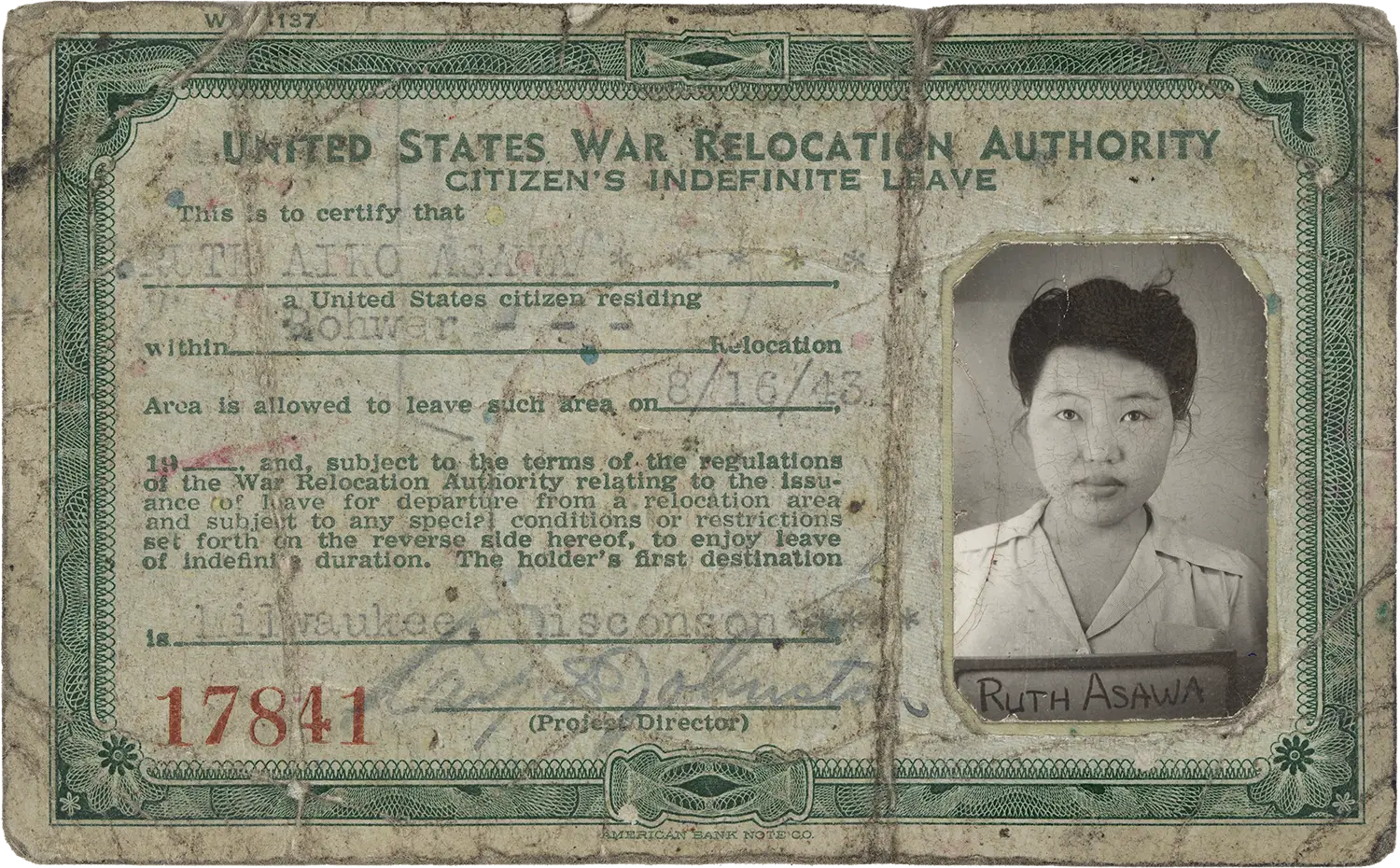

Anonymous identities often don’t emerge as an organic, bottom-up social phenomenon, though. Rather, they tend to be imposed from above, as detailed by political scientist and anthropologist James C. Scott. In his 1998 book Seeing Like a State, Scott describes the social machinery required by any government to perform its usual functions: taxation, military conscription, representation (maybe), and prevention of rebellion (as needed). To exert power over its people, the state must first render those people “legible,” meaning that they must be identified, counted, classified, and quantified. The state will want to know where you live; this is why, once sedentary farming has made statehood possible, and an aspiring state has marked out its borders, life within those borders becomes increasingly difficult for wanderers, nomads, travelers, gypsies, and the houseless—anyone whose coordinates (not to mention allegiances, property rights, and obligations) can’t be pinned down. 18

Even more fundamentally, in a large organization or modern state, your name must be standardized. This is no small feat, given that in many traditional societies, names are far from stable:

[…] [I]t is not uncommon for individuals to have different names during different stages of life (infancy, childhood, adulthood) and in some cases after death; added to these are names used for joking, rituals, and mourning and names used for interactions with same-sex friends or with in-laws. Each name is specific to a certain phase of life, social setting, or interlocutor. 19

Hence, legal names and permanent surnames (in patriarchal societies, typically patronymic) have often been government-imposed—whether during the Qin dynasty in China, the European Middle Ages, or more recently, the Philippines under Spanish rule. 20 Paradoxically, it’s precisely a state or other large organization’s ability to individually identify inhumanly large numbers of people that allows it to issue passports, driver’s licences, ID badges, uniforms, and membership cards vouchsafing anonymous identities for citizens, employees, or club members. In other words, it’s only by becoming individually legible to the state that we can become anonymous to each other.

Insect colonies offer a striking parallel. Calling the large reproductive female at the heart of a colony its “queen” is a misnomer, as she doesn’t rule, but she does, like a state, play a key role in defining colony membership through anonymous identity. Ants have “smells” that, as with human anonymous identity, derive in part from a place (a common environment and diet), from their version of a profession, or “caste” (worker vs. drone, for instance), and from a genetic line (chemical markers inherited from common ancestry). In this sense, while chimps have only first names, ants have only last names, something like “London-Baker-O’Connor.” 21

As Jonathan Haidt’s “chimp plus bee” formula implies, modern humans combine both kinds of identity; and unlike ants or bees, we have repurposable mental machinery—language—allowing us to coin new symbols and form new identity groups at will. Hence for us, identities don’t develop at the leisurely pace of biological evolution, but at the increasingly breakneck speed of cultural evolution. Today, every new social media hashtag offers a potential identity marker.

The onslaught of new and overlapping identities can be exhausting. You might be fantasizing about how life would be without identity politics, but insular, “first name only” societies are far from peaceable paradises. Inequality and oppression still exist in the context of individual relationships—just as for our chimpanzee cousins. Squabbles can turn violent, murder can be commonplace, escaping an abusive situation can be near-impossible, and bonds of friendship or kinship with wronged parties can lead to cycles of revenge and feuding. Life is precarious, whether you’re a bullied underdog or a paranoid “alpha,” on top for now but always looking over your shoulder.

In anonymous societies, broader social cohesion, shared norms, division of labor, and sheer scale (which allows for more consistent resource sharing, diversification, greater mobility, and risk pooling) can give us significantly more individual security. Laws, customs, rights, and social safety nets can let us live together without having to rely on continual one-on-one negotiation, patronage, and goodwill—or under the constant threat of random violence. On the whole, this seems like progress.

However, such progress comes at a price, as we’ve seen. With its greater social control over a population that has been pinned in place, the state can be benevolent or tyrannical—and is typically both at once; an individual’s experience will depend on their position and caste or class within the society. A monopoly on violence allows powerful states to oppress their own people in ways that would be inconceivable to our mobile hunter-gatherer ancestors, who could always pull up stakes and move somewhere else if things got ugly. Moreover, even if life in a big city feels safer than worrying about being picked off by an enemy raiding party, it can come at a cost of diminished personal freedom, disconnection, and alienation.

Describing a termite colony, the late English scientist James Lovelock noted,

The individual worker who once lived freely on the plains now spends a lifetime gathering mud, mixing it with shit and sticking the smelly bundle into gaps in the walls of the nest or anywhere their in-built programme instructs. Is something akin to this egalitarian paradise a model of future urban life? Passing a contemporary office tower, it is hard to ignore the termite analogy—in glass boxes everybody is doing exactly the same thing, not mixing shit but staring at computer screens. 22

Perhaps, then, it’s unsurprising that depression seems to be increasingly common in modern, affluent, anonymous societies. 23

Worse, the moment there’s an anonymous collective identity, there’s also an “us,” or in-group, and a “them,” or out-group, 24 on a scale that dwarfs individual friendship or enmity. 25 Super-colonies of Argentine ants might seem peaceful and cooperative, until we find the places where one super-colony borders another; there, the carnage is brutal, an invisible boundary shifting in a slow tug-of-war over the bodies of the dead.

It recalls the trenches of World War I. Individual German and English people in that war had no quarrel with each other, as the famous Christmas truce of 1914 vividly demonstrated. For a short time, soldiers on opposing sides of the Western Front put down their arms, played football, and sang carols together; but their national identities soon prevailed, turning every Hans or Gunter back into the anonymous “Jerry,” every William or Robert back into the anonymous “Tommy.” Dehumanized once more, neither individual empathy nor the shared norms of an anonymous in-group inhibited the ongoing violence.

Can there ever be an “us” without a “them”? Our future may depend on the answer to this question.

.webp)

Today, one of the most important functions of language is forming communities—negotiating their boundaries, naming them, identifying with them. Those overlapping communities are the social laboratories where culture, specialized knowledge, and technology develop. Certain communities may have widely agreed-on prerequisites for membership, some of which are hard to change, such as skin color or sex characteristics. Some, like language, accent, skills, clothes, and hairstyles, can be acquired to one degree or another, though it may be costly. Yet other communities may be quite abstract. When membership in a community relies on a document for proof, like a passport or a union card, it has clearly become so unmoored from an individual body that it has entered a realm of pure ideas.

Chimps, then, wouldn’t be able to answer questions on a survey about identity, because even though they can acquire enough symbolic language to understand “first names,” they don’t live in anonymous societies, hence they lack anonymous identity. Their natural mistrust of strangers isn’t softened by the idea that the stranger, because of some kind of team marker, is “one of us”; on the other hand, neither are they especially prejudiced against a stranger who is “one of them.”

That’s why, despite the popularity of Chimpanzee Politics in Washington, neither the “build a wall” campaign nor the characterization of an opposing group as a “basket of deplorables” (to use the tribal language in play in the 2016 election) would work on real chimps. Unlike ants or people, it would be hard to convince chimps to go to a rally or march in the street, let alone die for a country, political party, or cause—because that would require identifying with a country, political party, or cause.

There’s a difference in purpose between a population that has anonymous societies and one that doesn’t. It’s an oversimplification to claim that everything we do is driven by any single purpose, but let’s suppose, as Darwin did, that an organism “succeeds” insofar as it manages to reproduce. For a chimp, success means raising baby chimps. For ants, success means reproduction of the whole colony, which is not the same—it’s entirely compatible, for example, with sacrificing many individuals in war.

A colony can be thought of as a single body rather than a collection of individuals. We wouldn’t say that a large person is “more successful” than a smaller person, just because a larger body is made up of more cells. Nor do we mourn the death and sloughing-off of our skin cells, or worry about the short lifespans of our white blood cells (those only last a couple of weeks). Since ants within the same colony are genetically very similar (or even clones!) 26 and their brains aren’t wired for individual relationships with other ants, the analogy between ants and cells in a body is quite close. Arguably, the colony is the organism.

So where does all this leave humanity? I would argue that we’re in the midst of a great transition. “Humanity 1.0” was more chimp-like, while “Humanity 2.0” is increasingly ant-like—though we remain a mixture of the two. Can we really still think of ourselves as “90% chimp,” though? Success for us used to mean biological reproduction. Now, it’s shifting toward cultural reproduction.

We can easily see this transition playing out in front of our eyes, once we know where to look: trends in the birth, death, and reproduction of our bodies; and trends in the birth, death, and reproduction of our identities. This is why, in my own research, I eventually began to ask questions about gender and sexuality, which lie right at the crossroads between reproduction and identity.

The chapters that follow tell a story about human identity and how it’s evolving, based on six years of surveys answered by tens of thousands of people in the US. It’s a story I’ve pieced together by combining data analysis, my bread and butter as a researcher, with study and consultation from experts in fields where I have no formal training—including ethnography, sociology, psychology, anthropology, demography, gender studies, and medicine. I’ve also learned directly from thousands of pages of candid comments from a wide range of survey respondents. The picture that emerges by bringing all of these elements together has surprised me at every turn, and feels important to share.

A few disclaimers are in order, though. To focus so much of this book on gender and sexuality may puzzle some readers, given the many other identities fraught with marginalization and systemic bias—especially, in the American setting, race. While I’ll touch on race in the context of urbanization, I’ll do so only tangentially. I focus on gender because it’s so tightly bound to the fundamentals of biology and reproduction. As the controversial feminist writer Shulamith Firestone put it in her 1970 book The Dialectic of Sex,

The division yin and yang pervades all culture, history, economics, nature itself; modern Western versions of sex discrimination are only the most recent layer. […] [F]eminists have to question, not just all of Western culture, but the organization of culture itself, and further, even the very organization of nature. 27

Modern readers of Firestone have noted her obliviousness to the racist dimensions of the culture she critiques—yet remains embedded within. 28 I’ll elaborate on some of these dimensions in Chapter 4, and take a step back from “Western” ideas about sex, gender, and the family to consider a wider historical context.

Nonetheless, Firestone’s central insight is worth taking seriously. Beyond biology’s “yin and yang,” modern societies have accumulated a great tangle of gender, sexual, and relationship models, power structures, taboos, preferences, kinks, and orientations. Yet these cultural structures are built on a foundation tracing all the way back to the evolution of sex itself by single-celled lifeforms that predate even the distinctions between animals, plants, and fungi.

In this sense, the biological reproduction-focused “Humanity 1.0” is not only far older than the US, but far older than humanity itself. Our ongoing transition to “Humanity 2.0,” the reproduction of identities, may be a shift as profound as the emergence of multicellular organisms 600 million years ago, in which language serves as the new DNA.

You may be wondering how it’s possible to draw broad conclusions about humanity based on a sample of respondents from just one country. In general, that should arouse skepticism, and yes, these conclusions should be regarded as tentative.

My focus on the United States emerged as a result of two constraints: practical limitations in my surveying methods, and the way cultural barriers complicate apples-to-apples comparisons between countries. While many of the trends we can see in the US data are being felt elsewhere too, asking the right questions to get at those underlying patterns would require nuanced local knowledge. 29 The US is itself far from culturally uniform, and as you’ll see, plenty of evidence indicates that even here, we don’t entirely agree on what the most basic words mean.

Still, as a large country with disproportionate influence around the world, whose language is spoken by the largest number of people on Earth, and whose technical infrastructure allows for this kind of surveying, the US is a reasonable place to begin. As we start to make out the deeper patterns in the US data, it’ll also become clear that many of these are functions of demography, urbanization, technology, and new media—trends that are increasingly global, not local. Where applicable, I’ll supplant survey data with publicly available international and historical data to support the broader conclusions.

Although neither I nor anyone else can claim to have a “view from nowhere,” I’m writing in a spirit of open-ended inquiry. The research that went into this book has been, for me, an extended and at times thrilling process of discovery. I would like to take you on a guided tour of the insights, as I experienced them. This means doing more than just offering up unattributed conclusions or factoids to bolster an argument; the idea is to show, not tell.

That’s why this book has so many graphs, rather than just citing a percentage here and there. Graphs are harder to fudge than out-of-context “lonely numbers,” to use public health expert Hans Rosling’s term:

It is instinctive to look at a lonely number and misjudge its importance. […] Never, ever leave a number all by itself. Never believe that one number on its own can be meaningful. If you are offered one number, always ask for at least one more. Something to compare it with. 30

Amen! A graph can tell a nuanced story, show margins of uncertainty, and even reveal how the same raw information could be used (or misused) in the service of different agendas. By showing my work, I hope to convince you of some findings that, frankly, I wouldn’t have found believable had I not seen the data myself.

In approaching the evidence both openly and critically, you will become a data scientist too. This will let us explore questions about causality, sources of error, and different possible explanations for what we see. It feels more honest—and it’s more interesting—to delve into ambiguities when we find them, rather than sweeping them under the rug to make the narrative tidier. Reality is often surprising, but seldom simple.

If you’re more of a stories person than a numbers person, I hope you, too, will find much to enjoy here. There’ll be no equations (except in the Appendix for data nerds), and everything will be explained in plain English. Also, in the “show, don’t just tell” spirit, the book is full of quotes and accounts directly from respondents, domain specialists, and historical sources. No citation or quotation should be mistaken for endorsement. Sometimes, what the supposed “experts” have had to say over the years needs to be seen to be believed.

However, open-mindedness is important too. We’re living in a time of such rapid and uneven changes in norms that it’s easy to become disconnected from those not in our geographic, generational, and cultural cohort. We can feel disoriented when confronting the views and lived experiences of people outside our bubbles, especially when these seem outlandish but are (or were) mainstream within their own communities. Yet this exposure feels crucial, both to understand the bigger picture, and to counteract the forces pulling us apart today.

Many of us are finding ourselves bewildered, unable to understand large segments of our society. Most of us do not understand, either, how alien the recent past was. This is an opportunity to listen, learn, and place our own views in context.

Who Are We Now? comes in three parts, mirroring my own journey through this territory and working like the stages of a rocket. Fueled by data and stories, each of them will lift us into a higher orbit; then detach, allowing us to take a breath, reorient ourselves; then fire up a new stage and venture farther out.

The first stage, Chapters 1–3, is like a booster rocket to get us off the ground: Handedness. The majority status of right-handedness is built into our biology. Across many cultures, it has almost universally resulted in a right-handed in-group and left-handed out-group, with real social consequences. This often unnoticed human trait may seem inconsequential—but it isn’t. If you’re left-handed, you’re probably nodding knowingly as you read. If you’re right-handed, you’re probably puzzled. That’s partly the point.

Beyond raising our consciousness, handedness offers us a practice run for a second rocket stage: Sex and gender, covered in Chapters 4–15. This is the heart of the book, treating the aspects of identity that many people consider the most private, and that are in dramatic transition, particularly for young city dwellers. This stage brings us from the familiar territory of (apparent) sexual and gender-conforming majorities to a population overview that reveals a more unfamiliar reality. It’s as if we’d begun at ground level on Main Street, USA, but the houses and storefronts were revealed to be a Potemkin village from above: many people’s private lives and selves are not as they present them publicly.

For our final stage, Humanity, we’ll be in a position to study ourselves literally from outer space. Chapters 16–21 zoom out to consider the forces that attract people to each other, not just individually but collectively, and how the action of those forces over time has resulted in profound changes to our planet that can easily be seen from orbit—especially on Earth’s night side, our cities glowing in the dark like skeins of fairy lights. Accelerating urbanization in the past couple of centuries has generated unprecedented cultural innovation and has been fundamental to the creation of the new identities explored in earlier chapters. Urbanization is also polarizing us culturally and politically in dangerous new ways. The book concludes with some guesses about (and hopes for) a broader, more inclusive future, predicated on a broader, more inclusive human identity.

In the quiet moments after each of these rocket stages has finished its burn and fallen away, I hope you’ll experience something like what I felt at certain points throughout the project. The feeling is like the so-called “overview effect” astronauts have described when they look back at Earth from outer space and confront the reality that we’re all living on a tiny, fragile ball hanging in the void. As the anonymous, collective voice of Wikipedia puts it:

From space, national boundaries vanish, the conflicts that divide people become less important, and the need to create a planetary society with the united will to protect this “pale blue dot” becomes both obvious and imperative. 31

The segment aired a few weeks later, on Episode #526 of the Lovecast.

Bellafante, “Why the Big City President Made Cities the Enemy,” 2020.

A 28-year-old from Burnsville, Minnesota.

A 55-year-old from Raleigh, North Carolina.

De Waal, Chimpanzee Politics: Power and Sex Among Apes, 1982.

De Waal, Different: Gender Through the Eyes of a Primatologist, 82, 2022.

Moffett, The Human Swarm: How Our Societies Arise, Thrive, and Fall, 2019.

Dennis, Shuster, and Slobodchikoff, “Dialects in the Alarm Calls of Black-Tailed Prairie Dogs (Cynomys ludovicianus): A Case of Cultural Diffusion?,” 2020.

Patterson, “The Gestures of a Gorilla: Language Acquisition in Another Pongid,” 1978; Pepperberg, The Alex Studies: Cognitive and Communicative Abilities of Grey Parrots, 2002.

De Waal, Our Inner Ape: A Leading Primatologist Explains Why We Are Who We Are, 142, 2005.

Barras, “Only Known Chimp War Reveals How Societies Splinter,” 2014.

Diamond, Guns, Germs, and Steel, 312–13, 2005.

Goodheart, “The Last Island of the Savages,” 17, 2000; Man, “On the Aboriginal Inhabitants of the Andaman Islands. (Part II.),” 150, 1883.

Moffett, “Human Identity and the Evolution of Societies,” 39–40, 2013.

There’s evidence of this same process in some other animals too, e.g. in resident orca populations, per Filatova et al., “Call Diversity in the North Pacific Killer Whale Populations: Implications for Dialect Evolution and Population History,” 2012. These researchers found that language among killer whales evolves slowly, is transmitted from one generation to the next, and can split into mutually incomprehensible dialects; also, bigger populations seem to support more complex languages.

Wissler, “The Culture-Area Concept in Social Anthropology,” 1927. Per Graeber and Wengrow: “At first, the most prominent exponent of the culture area approach was Franz Boas. […] Boas’s student and successor at the [American Museum of Natural History], Clark Wissler, tried to systematize his ideas by dividing the Americas as a whole, from Newfoundland to Tierra del Fuego, into fifteen different regional systems, each with its own characteristic customs, aesthetic styles, ways of obtaining and preparing food, and forms of social organization. […] Boas was a staunch anti-racist. As a German Jew, he was particularly troubled by the way the American obsession with race and eugenics was being taken up in his own mother country. When Wissler began to embrace certain eugenicist ideas, the pair had a bitter falling-out. But the original impetus for the culture area concept was precisely to find a way of talking about human history which avoided ranking populations into higher or lower on any grounds […].” The Dawn of Everything, 171–72, 2021.

There have been large-scale societies that didn’t rely heavily on farming, but spent part of the year roaming over a large area, only convening seasonally to create “temporary cities,” as described by Lowie, “Some Aspects of Political Organization Among the American Aborigines,” 1948. Obviously, this way of life requires a shared anonymous identity as well.

Nowadays, digital credentials, and especially a mobile phone number, are increasingly supplanting a home address as an enduring coordinate system for uniquely identifying people. While this enables new forms of digitally mediated nomadism (see Marquardt, The New Nomads, 2021), it also gives the state unprecedented new powers to contact, track, and surveil “digital nomads.”

Scott, Seeing Like a State, 64, 1998.

In the Philippines, the colonial government imposed surnames en masse, with entire towns sometimes assigned last names starting with the same letter, and whole regions of the map laid out alphabetically as if the land itself were an enormous collage made out of cut-up pages from a telephone book.

In a telling exception, a 2005 paper found that ant queens can individually recognize other queens, which may be beneficial in maintaining dominance hierarchies among the queens. Some larger-brained social insects, such as paper wasps, have also been shown to be capable of individual recognition. See D’Ettorre and Heinze, “Individual Recognition in Ant Queens,” 2005; Sheehan and Tibbetts, “Specialized Face Learning Is Associated with Individual Recognition in Paper Wasps,” 2011.

Lovelock, Novacene, 50, 2019.

Many ethnographic accounts support this view; for instance, American linguist Daniel Everett wrote of the Pirahã hunter-gatherers in the Amazon, “The Pirahãs show no evidence of depression, chronic fatigue, extreme anxiety, panic attacks, or other psychological ailments common in many industrialized societies. But this psychological well-being is not due, as some might think, to a lack of pressure […]. [T]hey do have life-threatening physical ailments [and] love lives [… and] they need to provide food every day for their families. They have high infant mortality. […] They live with threats of violence from outsiders who frequently invade their land. [… But] I have never heard a Pirahã say that he or she is worried. In fact, so far as I can tell, the Pirahãs have no word for worry in their language. One group of visitors […], psychologists from [MIT’s] Brain and Cognitive Science Department, commented that the Pirahãs appeared to be the happiest people they had ever seen.” Everett, Don’t Sleep, There Are Snakes: Life and Language in the Amazonian Jungle, 278, 2008.

Haldane, “Population Genetics,” 1955; Smith, “Group Selection and Kin Selection,” 1964; Hamilton, “The Genetical Evolution of Social Behaviour. II,” 1964; de Waal, The Bonobo and the Atheist: In Search of Humanism Among the Primates, 2014.

Consistent with this, strong evidence exists of a dramatic overall decline in violence throughout human history, as measured in violent deaths per capita; however, given exploding population numbers and the mechanization of warfare, the absolute numbers of people killed since 1900 dwarf those of historical conflicts. Further, five of the top ten most deadly mass killings in human history have taken place after 1900, in terms of death rate per capita per unit of time: World War II (number one), World War I (number three), the Russian Civil War (number eight), the Rwandan genocide (number seven), and Chinese famines associated with Mao’s Great Leap Forward (number ten). Sapolsky, Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst, 619, 2017.

Fournier and Aron, “Evolution: No-Male’s Land for an Amazonian Ant,” 2009.

Firestone, The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution, 2, 1970.

Lewis, “Shulamith Firestone Wanted to Abolish Nature—We Should, Too,” 2021.

The historical materials, too, focus on the United States and Western Europe, both because of my own limitations as a researcher and to offer timely context for the survey data.

Rosling et al., Factfulness, 128–30, 2018.

Wikipedia, “Overview effect,” 2020.