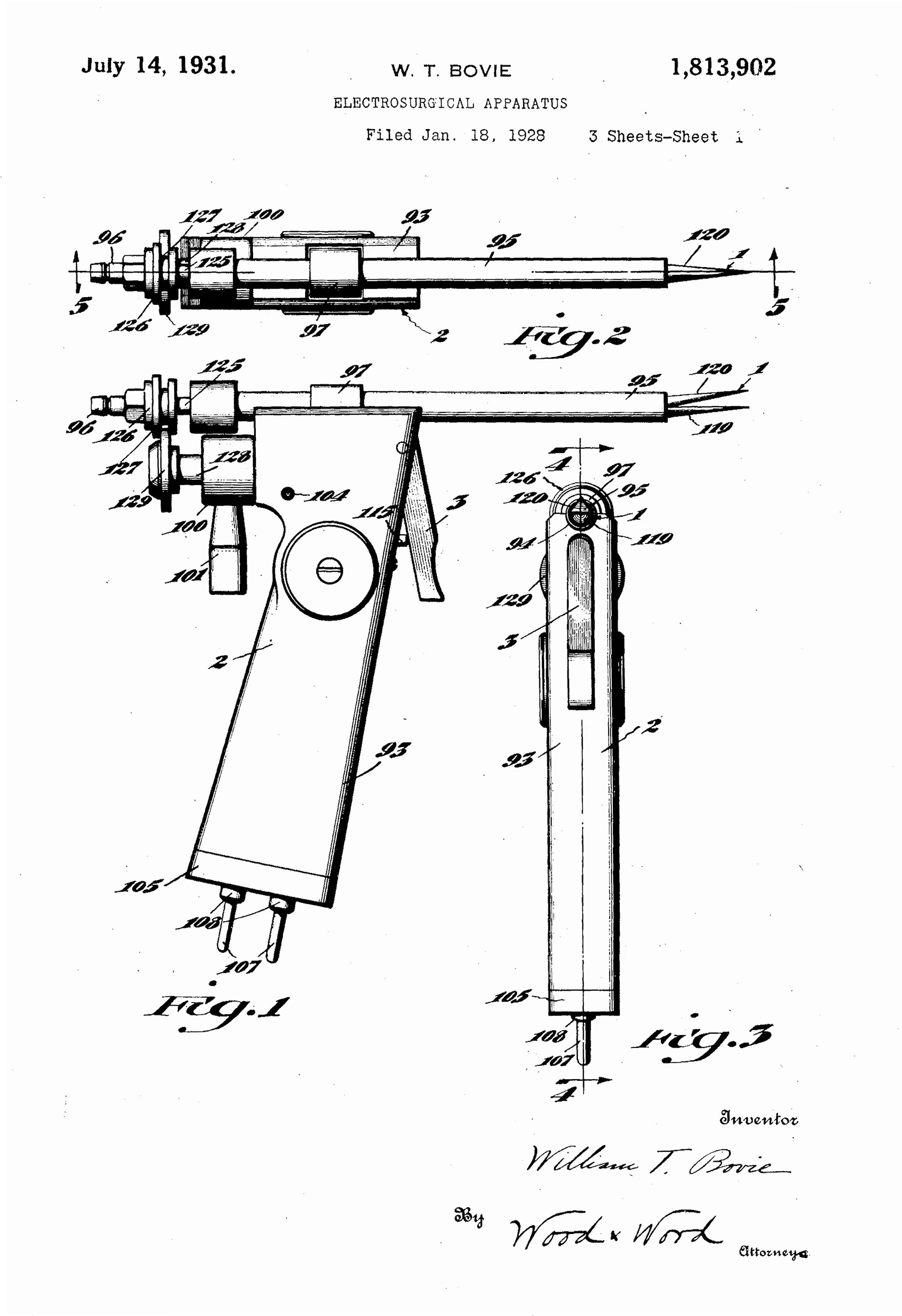

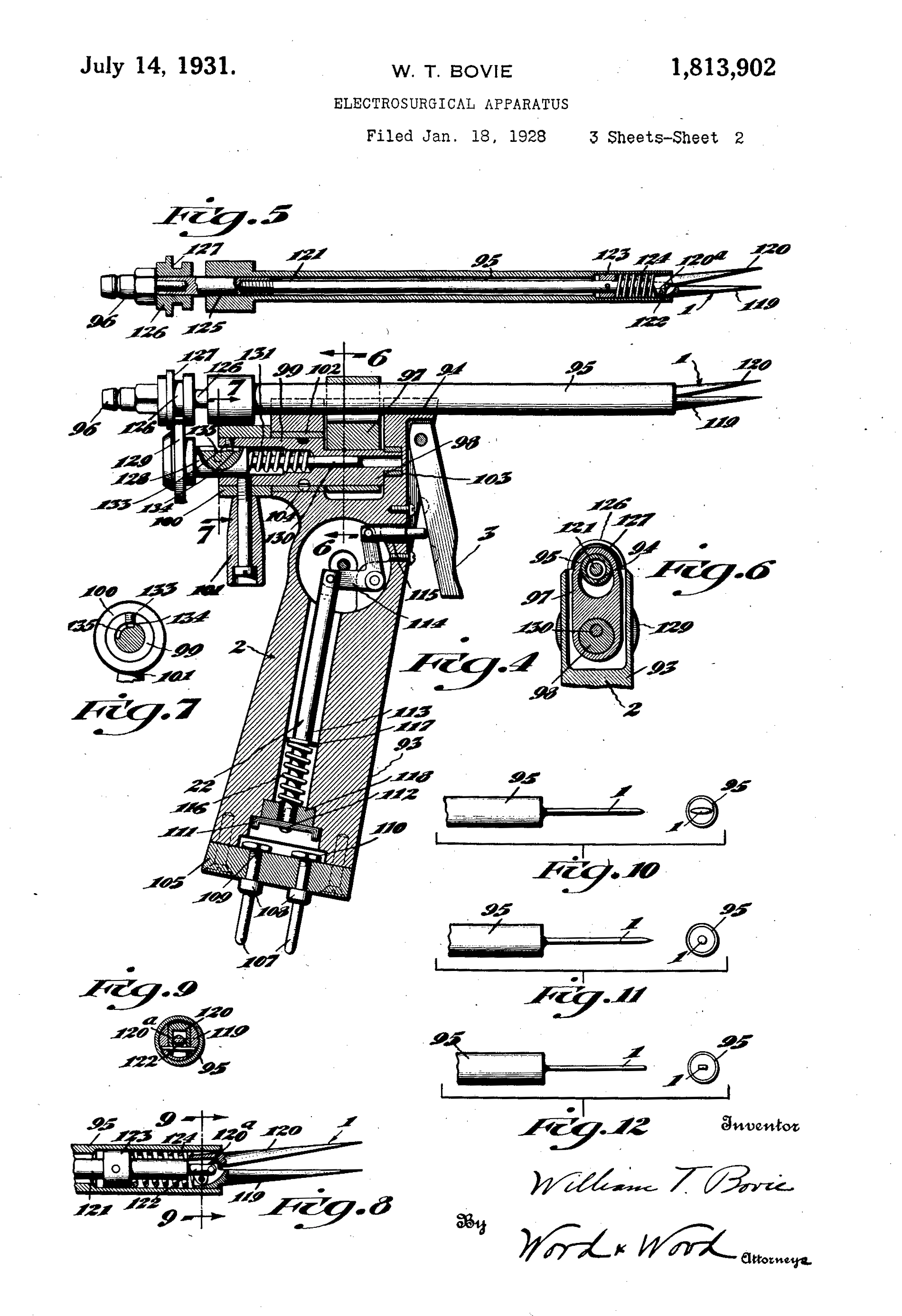

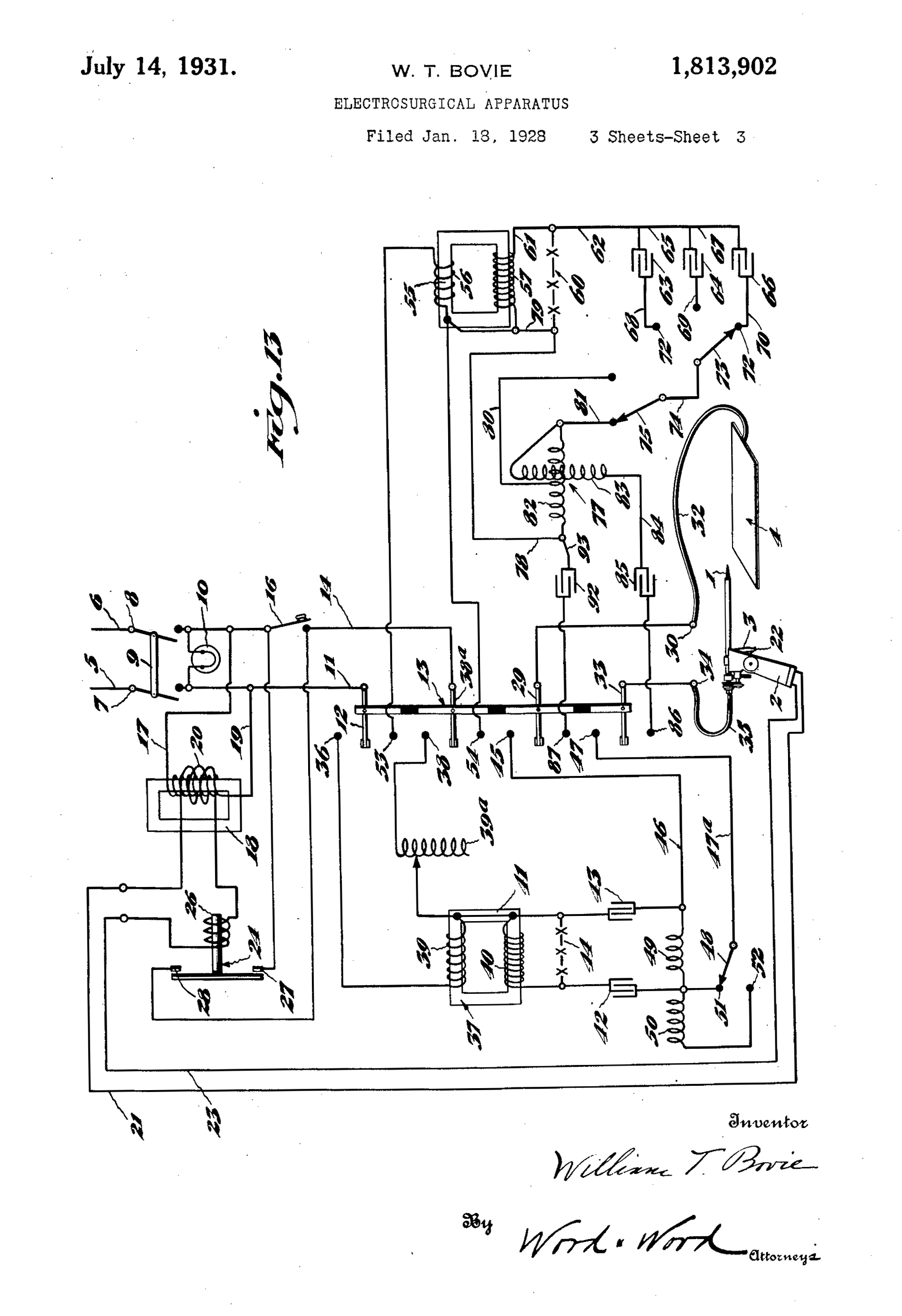

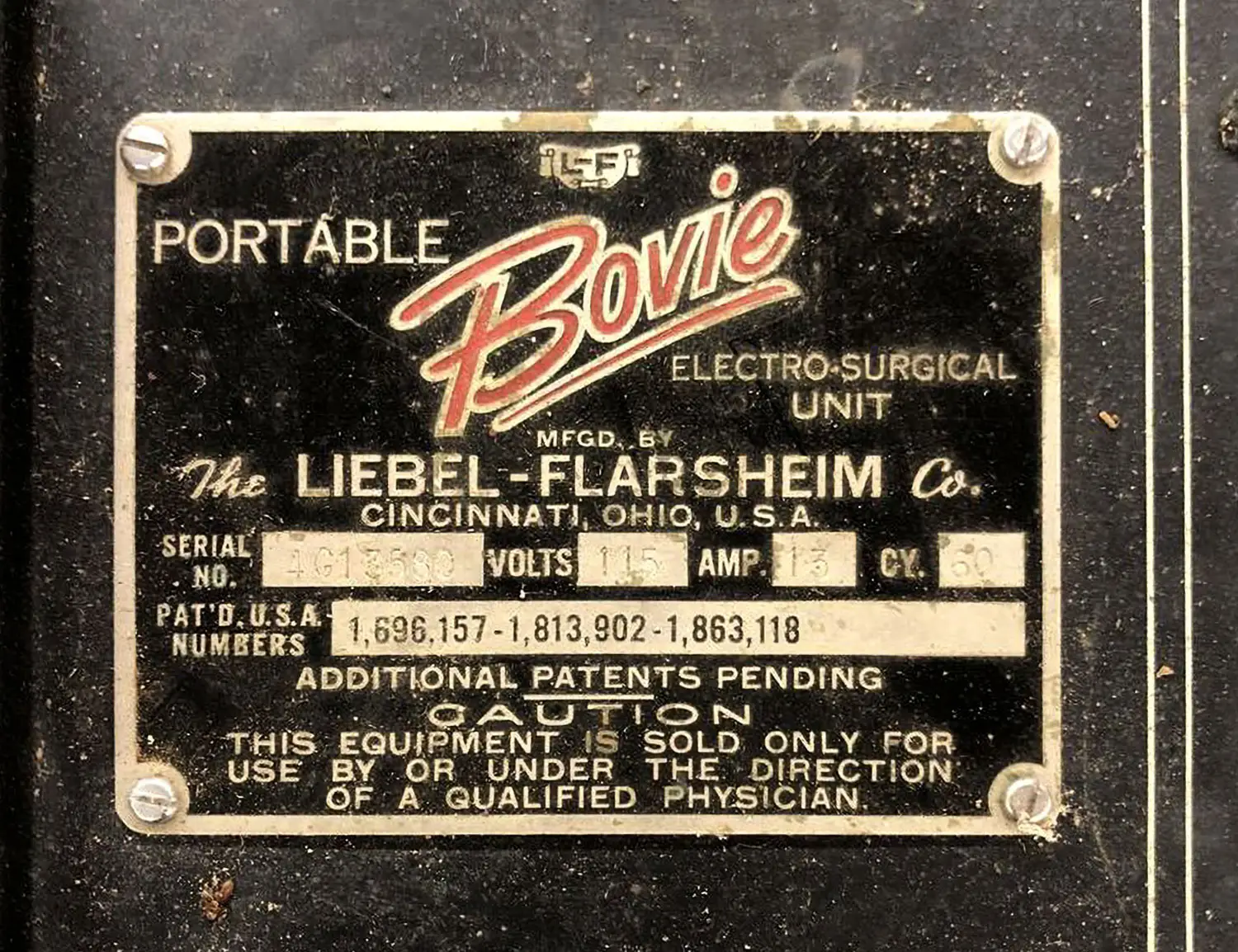

Had the details of David Reimer’s story been more widely known before the late 90s, it would likely have changed the course of treatment for thousands of other children. 1 For one thing, the kind of electrocautery device that injured him continued to be used for circumcision, and led to total destruction of the penis in an unknown number of other infants and small children too.

As recently as 2017, a retrospective paper titled Electrosurgery Use in Circumcision in Children: Is it Safe? concluded rather belatedly that the kind of “monopolar” device used for Reimer’s circumcision was, in fact, not safe. The authors added, “We believe that complications from using monopolar diathermy for circumcision are underreported.” 2 Worse still, parents and doctors of mutilated infants found themselves facing the same quandary that the Reimers had; but now, they thought they had a best practice to follow. Misinformed by the myth of a happy outcome in that case, a 1989 paper in the Journal of Urology 3 was still arguing for making Reimer’s treatment standard procedure:

Four patients who had traumatic loss of the penis were managed after the initial injury with a feminizing genitoplasty. Patient reconstruction ranged from 6 months to 3 years. […] Immediate results were considered to be cosmetically satisfactory in all patients. Followup ranged from 8 months to 23 years […]. The long-term results have been particularly gratifying in 2 individuals who have been observed for more than 18 years. Early feminizing genitoplasty offers an excellent method of reconstruction of the external genitalia in the child with traumatic loss of the penis who is assigned a female sex of rearing.

The Reimer story is of course a single anecdote, not real data. The four patients cited in this 1989 article are also far too few for strong conclusions—and I, for one, am leery of nominally expert claims that an outcome is “particularly gratifying,” which can paper over the same kinds of methodological and reporting biases Money’s claims did. The only people whose “gratification” should matter are the patients themselves, and I’d want to see their unfiltered feedback.

Nonetheless, it’s interesting that surgical and hormonal feminization of unambiguously male infants may sometimes “work,” even if it’s far from a best practice for male infants whose penises have been destroyed. The truth about whether a person’s eventual gender identification is alterable—whether at birth, in infancy, or even later in life—may depend more on individual circumstances than either John Money or his most vocal opponents would have it.

By the 1990s, narratives about gender identification were shifting, and Money’s theories were falling out of favor. In the long tug of war between gendered nature and gendered culture, nature began gaining ground once more. The change had a profound effect on the way doctors manage intersex newborns—and their parents. That shift is evident when intersexuality is broken down by whether respondents were assigned female at birth or male at birth. The resulting pattern is striking.

Respondents between 18 and 24 years old who know they’re intersex (so, roughly speaking, Millennials, born around or shortly before the year 2000), were 97% likely to have been assigned female at birth. On the other hand, it’s 78% likely that respondents between 58 and 74 years old (roughly corresponding to Baby Boomers, the generation born between 1946 and 1964) who know they’re intersex were assigned male at birth! The error bars of these curves are substantial, making the exact probability ratios uncertain, but the dramatic reversal from majority male to majority female assignment is unmistakable.

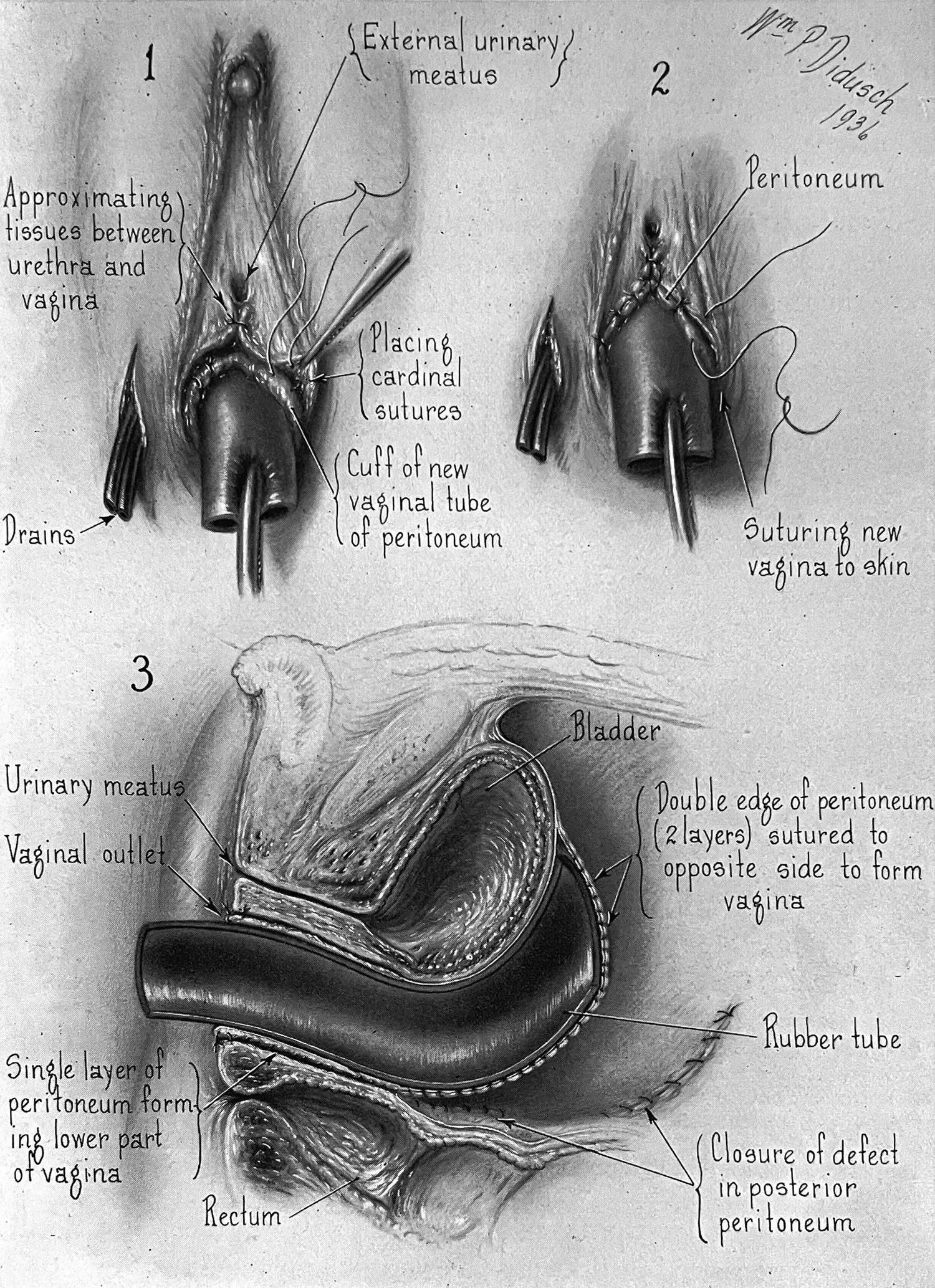

From a pediatric surgeon’s point of view, the old male default might have seemed counterintuitive. Gynoplasty was generally considered easier than phalloplasty; as a crude medical maxim from around 1970 held, “It’s easier to dig a hole than build a pole.” 4 It’s true that surgery to create a vagina doesn’t need to result in an externally visible structure that can look convincing at locker room distance, pass a stream of urine that allows one to pee standing up, or (most difficult) produce an erection. This is all, as it were, a tall order for plastic surgery, sometimes requiring a suspension of disbelief on the part of the beholder. John Money uncharitably described early attempts at phalloplasty as producing a “lump of meat” 5 —though techniques have since improved.

Focusing on superficial impressions also sets a low bar for surgical vaginas, though. As an intersex adult who underwent feminizing surgery put it in an interview, “I don’t look like everyone else does. Not at all.” When asked if her vagina carried sensation, she answered, after a long drag on her cigarette, “There’s always lack of sensation where there’s scarring.” 6

However, this kind of surgery wouldn’t have been the norm for an intersex birth a few decades ago, since, as the data show, intersex babies were almost always assigned male at birth. Indeed, given the multiple surgeries needed for feminization (often spanning childhood and adolescence) it would have been hard to carry such a program out without the patient’s understanding—and most intersex Boomers weren’t informed of their condition. How could a person’s intersexuality be kept secret, both from themselves and from their parents?

The key was not starting from scratch. For most Boomers born with genital variations, the doctor’s judgment was that relatively minor “corrective” hypospadias surgery of the kind William Hammond described in the 19th century, combined with hormone treatment, could “finish the job” of making a penis out of a micropenis or clitoris, as described in Chapter 11. The surgery could be done well before (the theory went) the infant became self-aware enough to form a fixed gender identity. Regardless of what happened on the inside, any available plasticity in the body was mobilized to nudge the outwardly visible genitals toward unambiguously male, on the presumption that psychological plasticity would allow the child’s inner sense of self to follow suit.

Perhaps, also, there was a bias in play whereby answering the first question with “it’s a boy” was deemed preferable, all things being equal, to “it’s a girl.” One sign of that widespread bias is the frequent infanticide or death through neglect of baby girls in many countries, a practice that in recent decades has shifted to include selective abortion of female fetuses. In 1990, Nobel Prize winning economist Amartya Sen shocked the world with his analysis of this phenomenon, suggesting that due to sex-selective abortion and infanticide there were 100 million “missing women.” 7

On the other side of the coin, perhaps “noisy feminists” of the kind David Gelernter liked to complain about were starting to make doctors uncomfortable with the idea of cutting off clitorises willy-nilly, despite John Money’s oft-repeated claim that it didn’t affect a woman’s ability to orgasm. (This would have been news to the likes of William Acton and John Harvey Kellogg, on their surgical quests a century earlier to eradicate “nymphomania” through clitoridectomy.)

Human Rights Watch findings are in agreement with the conclusion that intersexuality has historically been “male by default”:

US government data compiled from several voluntary-reporting databases […] show that in 2014—the most recent year for which data are available—hypospadias surgery was reported on children 505 times, and clitoral surgery was reported 70 times. 8

In other words, when surgery was performed on intersex children, it favored “rounding them up” to male by a factor of 7.2x. 9

Why, then, is there such a dramatic shift toward female assignment at birth for younger intersex people?

Increasing levels of environmental pollutants that disrupt prenatal hormone levels may be part of the answer. In their 2021 book Count Down, Shanna Swan and Stacey Colino argue that these pollutants pose a looming fertility crisis, and have been feminizing us all—leading, among other outcomes, to declines over recent decades in testosterone level and sperm count among men. 10 They also argue that prenatal exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals may be a driver of increasing levels of gender dysphoria and non-binariness.

While these theories can’t be ruled out, the way Swan and Colino reach for biological explanations while discounting cultural change seems questionable, given the powerful evidence in the survey data of social transmission (meaning: people being influenced by others). The Count Down effect is also unlikely to account for the nearly 180 degree turn in intersex gender assignment that began taking place in 1990 or so.

Something else happened around 1990 that may offer a better explanation: doctors started to change their policies. Furtively performing “corrective” surgery at birth, and keeping children or even parents in the dark about it, at last began falling out of favor. The abstract of that Human Rights Watch article in its entirety reads:

Intersex people in the United States are subjected to medical practices that can inflict irreversible physical and psychological harm on them starting in infancy, harms that can last throughout their lives. Many of these procedures are done with the stated aim of making it easier for children to grow up “normal” and integrate more easily into society by helping them conform to a particular sex assignment. The results are often catastrophic, the supposed benefits are largely unproven, and there are generally no urgent health considerations at stake. Procedures that could be delayed until intersex children are old enough to decide whether they want them are instead performed on infants who then have to live with the consequences for a lifetime.

While it’s still the case that vanishingly few intersex 18-year-old Americans know they’re intersex, fewer of them are being operated on or given sex hormones as infants nowadays. This reflects a number of converging trends. One is an acknowledgement, based on hard lessons, that John Money was wrong about gender identity being entirely socially determined. Another is the increasing regard for the agency of the children themselves, a sense that they’re people whose rights to self-determination must be protected even—or especially—when they haven’t yet developed the self-awareness to make their own decisions.

Leaving their options as open as possible then becomes the priority, and avoiding early surgery or hormones now seems to many more in line with defaulting to female than to male. A large clitoris really isn’t the end of the world. Biologically, one can think of the physical development of a fetus as starting out female, with subsequent male development triggered by the addition of hormones; as English endocrinologist Richard Quinton has put it, “the default blueprint is female.” 11 There’s a degree of flexibility in the timeline for virilization; a micropenis can always be grown or made into a not-so-micro penis later on. As an ahead-of-his-time 66-year-old put it in the survey, “I was born both male and female. Raised female until 6 and then surgically aligned to be all male. Have lived male ever since, and identify as male.” Presumably, by 6 years old, this man’s sense of his own gender was clear enough that surgery (and probably hormones) could align him with what he felt he was on the inside, rather than having to face David Reimer’s lifelong ordeal.

The change taking place now is more profound, though, than just a shift from defaulting to male to defaulting to female. The whole notion that the sex binary is absolute, that the requirements of masculinity and femininity are set in stone, and that either/or choices are mandatory is beginning to dissolve. Leaving options on the table for an intersex child means being honest with them from the beginning about their non-binary status—“both male and female,” exactly the ambiguity John Money found so horrifying.

Once we abandon the idea that sex must be either/or, we also need to contend with the question of how big the excluded middle really is. How many people are actually intersex? As will now be clear, this question can’t be answered objectively, because most of the variables determining sex aren’t discrete. It’s like trying to establish how many people are ambidextrous. The only principled approach is to just ask people, and accept that both their answers and their definitions will vary.

Perhaps the percentage isn’t so important, as long as we recognize that it isn’t negligible. In practice, the only questions we really need to answer are: which infants do we perform sex assignment surgery on, and what pronouns should we default to using with them? Increasingly, the answer to the first question is “none, unless medically necessary” (i.e. except in the very small minority of cases where differences of genital development pose an immediate health risk). And for increasing numbers of young people, the answer to the second question is “they/them,” regardless of how their genitals look. For millions of people living in places where the gender binary no longer reigns absolute, not conforming to the binary no longer means “living apart,” as it might have in the 1960s.

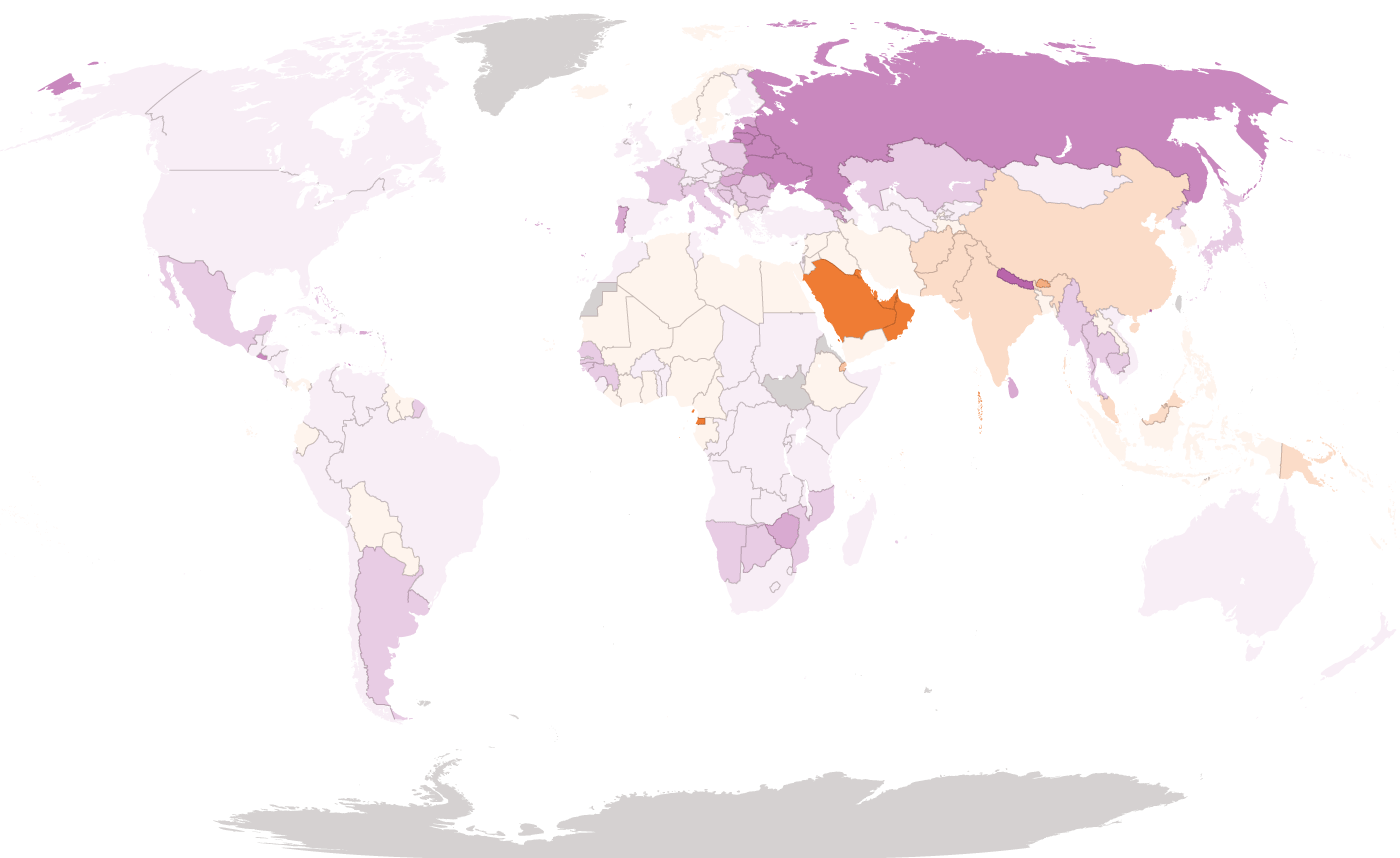

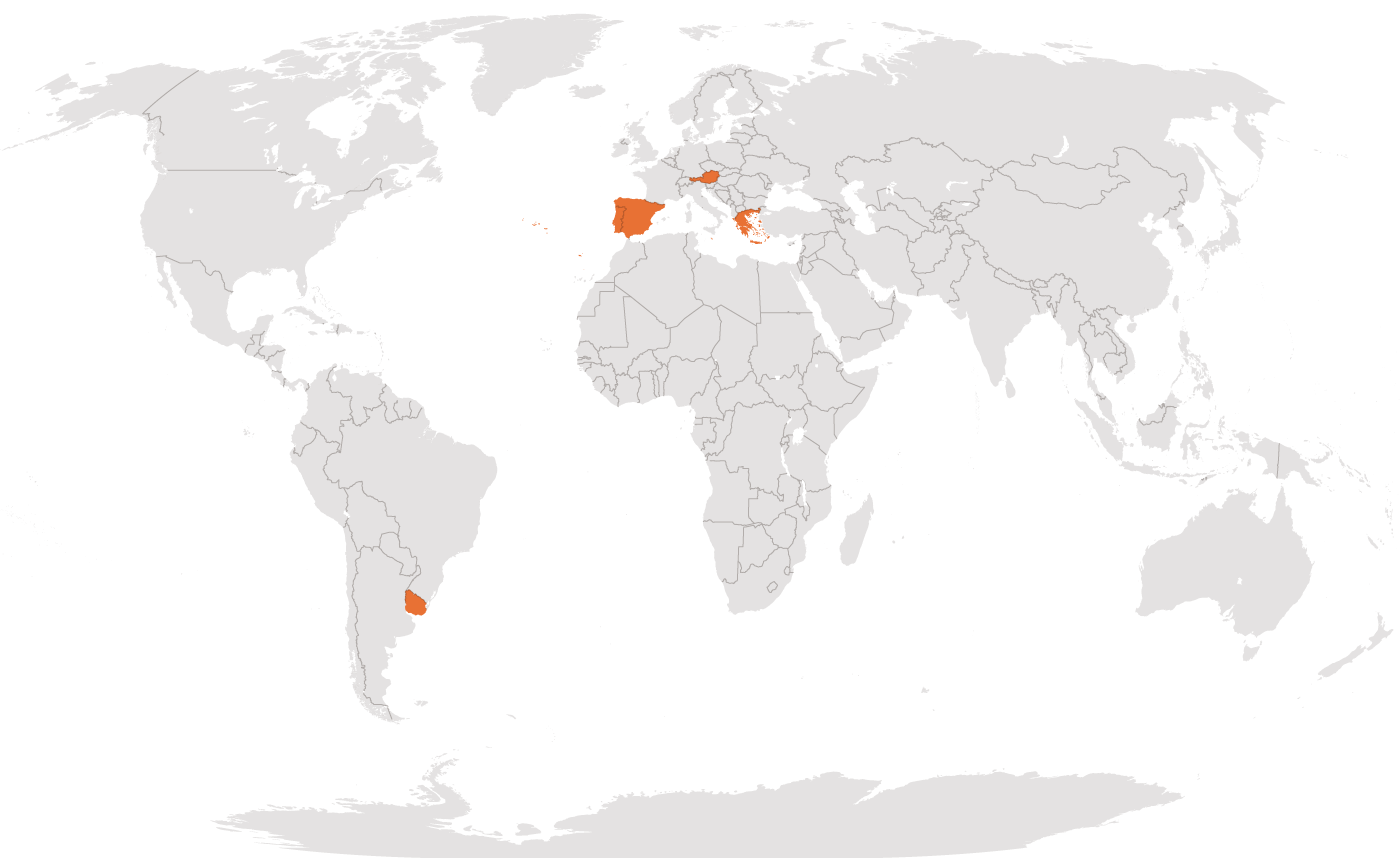

Medical practice is well ahead of government regulation with regard to sex assignment surgery for infants, but laws have slowly started to change too. In recent years, a tiny handful of countries 12 —spurred by intersex activists—have made it illegal for medically unnecessary surgeries to be done at birth, or more broadly, non-consensually. In this view, consent is necessary for such surgeries to be regarded as gender confirmation as opposed to genital mutilation. And newborns can’t give consent. This is consistent with the most basic statement of the Hippocratic oath, which medical students have been taking in one form or another for millennia: “First, do no harm” (Primum non nocere). David Reimer’s doctors violated the oath catastrophically, not once, but twice.

Austria

Portugal

Spain

Greece

Uruguay

Malta

Non-binary gender identification is also increasingly available on official forms and documents, though here too, official acknowledgement lags a reality in which one in twenty young Americans identify as non-binary.

Rosie Lohman, born intersex in Ontario in 2012, embodied many of these historic shifts. Although chromosomally XX, Rosie was born with a noticeable genital variation due to the high levels of testosterone common in children with Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia. A team of specialists attempted to pressure the parents, Stephani and Eric, into signing off on “corrective” surgery, which would have included clitoral reduction as well as the creation of a surgical vagina. But the Lohmans didn’t go along with the plan. As a CNN article on their story put it in 2020,

Rosie is now in the process of figuring out her gender identity on her own terms. While she says she still likes to use female pronouns for now and wants to keep her name, Rosie says that sometimes she feels like a boy and other times, nonbinary. “Because I am both!” she said. […] She has one piece of advice for new parents of any intersex baby who might be worried for their future, offered with a smile. “Calm down!” 13

It was a good call: in 2023, Eric Lohman wrote, “Our child no longer uses the name Rosie, nor does he identify as a girl, which I think speaks volumes about our decision to delay surgery.” 14

That it’s possible to be both public and calm about sex and gender non-binariness is very much a feature of our era. A 2019 article in Teen Vogue about intersexuality includes the stories of nine “out” intersex teens, Bria (they/them), Banti (they/them), Johnny (all pronouns), Cat (she/her), Anick (he/him), Francis (he/him), Irene (she/her), Mari (they/them), and Danielle (she/they). 15 Most were kept in the dark throughout childhood and experienced shame, isolation, and confusion before discovering online intersex communities and embracing intersexuality as a component of their identity. These experiences are familiar to many LGBTQ+ people, and the language many young intersex people are using is starting to overlap with these adjacent communities.

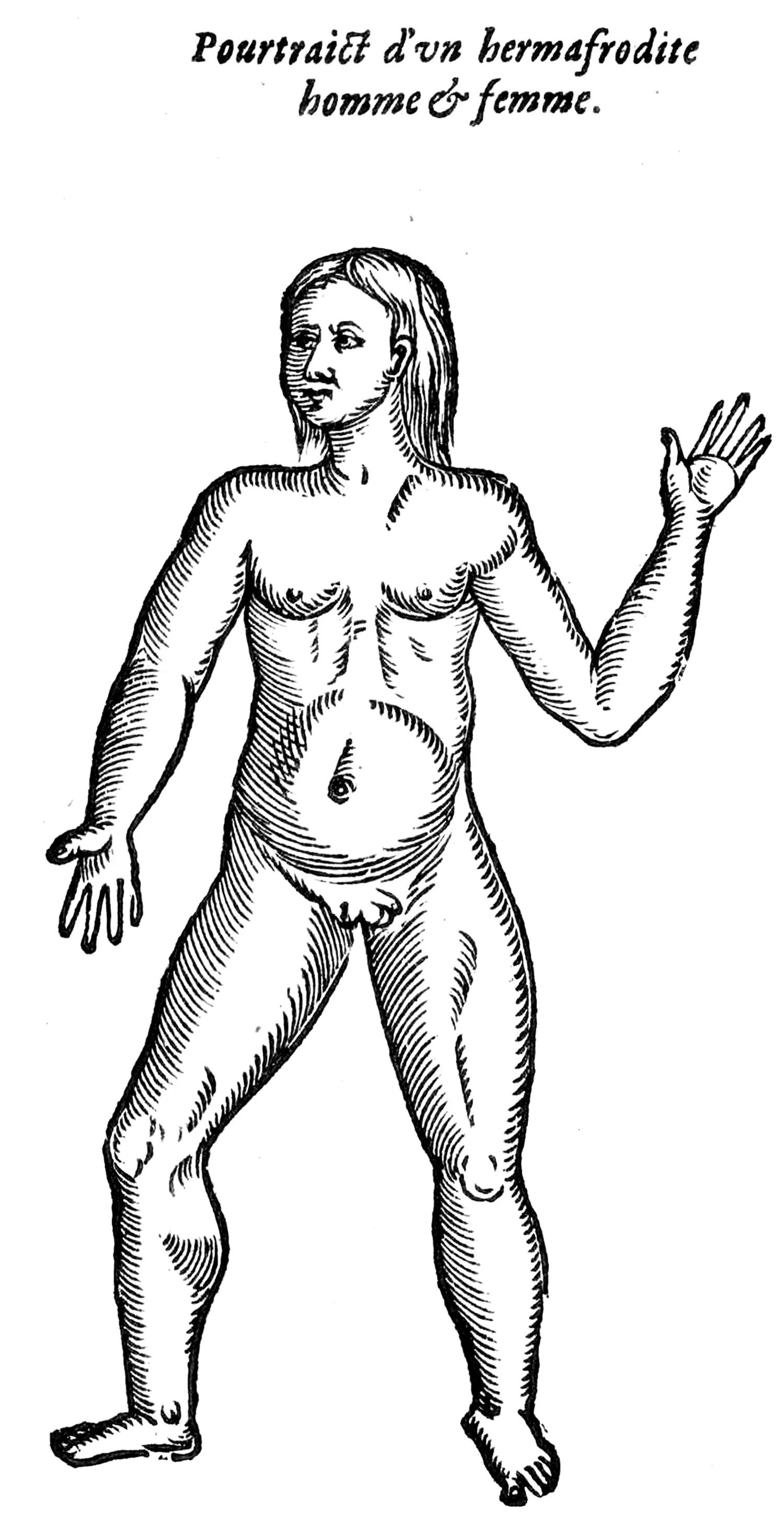

The embrace of historically excluded middles seems to be part of a profound and larger shift in the way we think about identity, but it’s important to put the rigidity of the 20th century sex and gender binary into a broader historical context. Anthropologists, historians, and social scientists aren’t immune to the powerful biases we all encounter when we view other cultures through the lens of modern Western categories and assumptions. Cultural biases lead to a kind of selective blindness, a bit reminiscent of the way we ignore our own noses, despite their occupying a sizeable part of our visual field. For instance, prior to the social strictures of Victorian England, it’s not clear that intersexuality (or any kind of sexuality) was as taboo as it became in the 19th century. A popular drinking song or “catch” by William Lawes (1602–1645) went:

See, here comes Robin Hermaphrodite,

Hot waters, he cryes for his delight:

He got a Child of a Maid, and yet is no man

Was got with childe by a man, and is no woman. 16

Arguably, colonialism has played a major role in erasing the formerly widespread acknowledgment of non-binary sex or gender in many societies. In South Asia, hijras have been long recognized as a third gender, neither male nor female; India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Bangladesh still acknowledge a third gender on official documents, though the legacy of British law in India criminalized non-procreative sexuality until 2018. 17 Many Native American cultures, too, have long recognized non-binary sex and gender in various forms, with the modern umbrella term “Two Spirit” reclaiming a range of such traditions. 18 Among the Zapotecs of modern-day Mexico’s Oaxaca valley, the muxes were—and and still are—a third gender. 19 Japan had a third gender, wakashū (若衆), before the country adopted Western sexual mores in the late 19th century as part of a broader movement to “modernize.” 20 There are many more examples in this vein.

.webp)

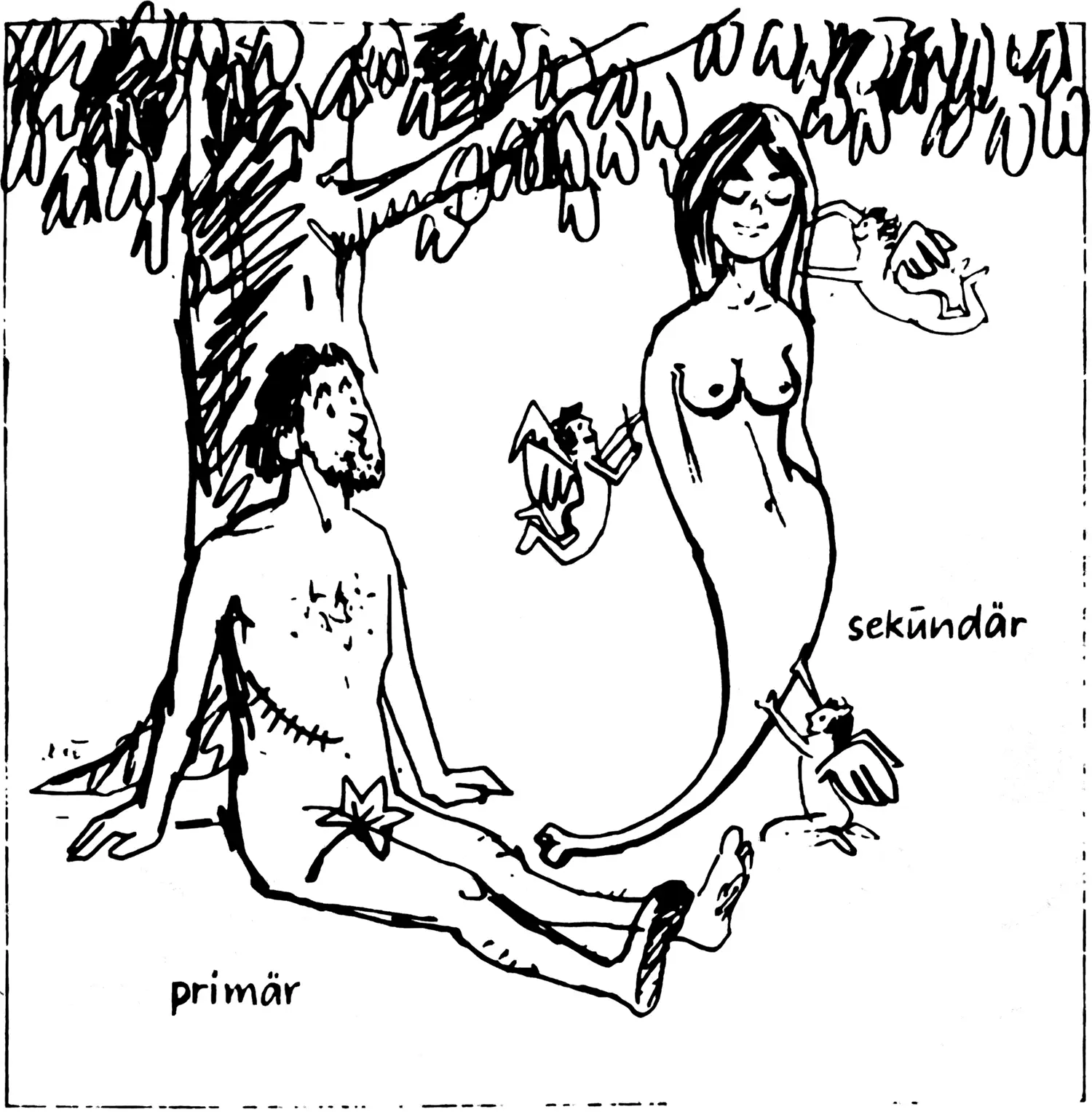

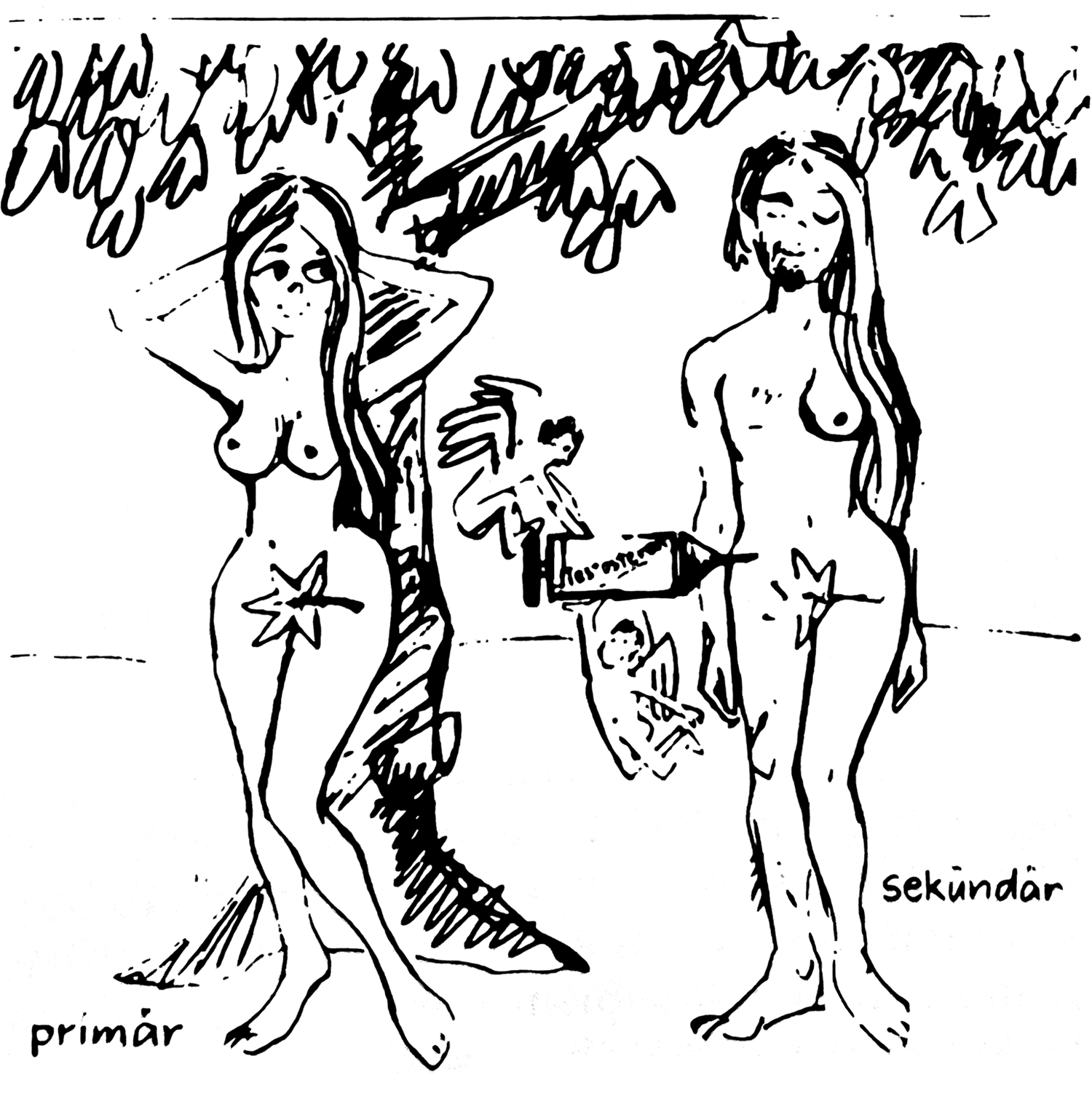

For thousands of years, traditional Jewish culture recognized multiple categories of intersexuality, including androgynos (אַנְדְּרוֹגִינוֹס), possessing both male and female characteristics, and tumtum (טֻומְטוּם in Hebrew, meaning “hidden”), possessing neither. Genesis Rabbah, a Jewish commentary on the Old Testament’s creation story written sometime between 500 and 300 BCE, asserts that Adam was created androgynos by God, with sex differentiation only occurring when Eve was fashioned out of Adam’s rib. In short, it may be that the cultural invisibility of non-binariness and intersexuality in recent European and American history is actually a historical anomaly—much like the Nuclear Family.

Even so, we should not fall into the opposite error of thinking that the emerging landscape of diverse gender and sex identities and increasingly broad acceptance of them is a historical norm. Most traditional societies are organized around sexual reproduction and its material requirements, and tend to marginalize those not involved in supporting this central project. This is because, as later chapters of this book will explore, for most people and throughout most of human history, it has been an existential challenge simply to scrape up enough calories to stay alive and propagate.

So, “Robin Hermaphrodite,” who may or may not have existed, 21 is celebrated for his extraordinary dual-mode reproductive capacity; but the framing—“got a Child,” “was got with childe”—is still very much heteronormative. Ancient Jewish thinking on the subject is framed legalistically, in terms of how marital obligations and patriarchal inheritance laws apply to such cases. Hijra communities tend to be marginalized and impoverished; relegated to a low social status, they often depend on survival sex work and suffer violence and abuse with impunity.

For a society to recognize the existence of non-binary and intersex people, in other words, is not the same as to accord them status and respect on their own terms. Today, many young people are willingly embracing non-binary identities with the expectation of equal respect and acceptance by peers.

Our greater modern understanding of the biological and physiological basis of sex is also new, as is our increasingly powerful ability to manipulate it. Ironically, the very techniques John Money and his collaborators marshaled to try to enforce the sex and gender binary of the ’50s are now among the tools being used to dismantle it. Emerging communities and changing attitudes have played at least as large a role. With or without medical intervention, sex assigned at birth is no longer the straightjacket it once was.

Per Colapinto, “Dr. John Money’s misreporting of his case had resulted in similar infant sex reassignments in thousands of other children.” As Nature Made Him: The Boy Who Was Raised as a Girl, 286, 2000.

Altokhais, “Electrosurgery Use in Circumcision in Children: Is it Safe?,” 2017.

Gearhart and Rock, “Total Ablation of the Penis After Circumcision with Electrocautery: A Method of Management and Long-Term Followup,” 1989.

Reardon, “The Spectrum of Sex Development: Eric Vilain and the Intersex Controversy,” 2016.

Downing, Morland, and Sullivan, Fuckology: Critical Essays on John Money’s Diagnostic Concepts, 80, 2014.

Colapinto, As Nature Made Him: The Boy Who Was Raised as a Girl, 227, 2000.

Sen, “More Than 100 Million Women Are Missing,” 2017.

InterACT and Human Rights Watch, “‘I Want to Be Like Nature Made Me’: Medically Unnecessary Surgeries on Intersex Children in the US,” 2017.

The literature sometimes claims the opposite—that female assignment for intersex babies has always been the norm—but that’s because hypospadias surgery is often neglected, i.e. the diagnosis of hypospadias (which is common) is understood as a “penis defect” rather than a marker of intersexuality.

Swan and Colino, Count Down: How Our Modern World Is Threatening Sperm Counts, Altering Male and Female Reproductive Development, and Imperiling the Future of the Human Race, 2022.

Saini, Inferior: How Science Got Women Wrong and the New Research That’s Rewriting the Story, 2017.

Trankuility, “Protection of Intersex Children from Harmful Practices,” 2016.

Neus, “She’s 7 and Was Born Intersex. Why Her Parents Elected to Let Her Grow Up Without Surgical Intervention,” 2020.

Personal correspondence.

Lindahl, “9 Young People on How They Found Out They Are Intersex,” 2019.

Peraino, Listening to the Sirens: Musical Technologies of Queer Identity from Homer to Hedwig, 206, 2006.

Hunter, “Hijras and the Legacy of British Colonial Rule in India,” 2019.

Flores, “Two Spirit and LGBTQ Idenitites: Today and Centuries Ago,” 2020.

Bushell, “Los Muxes: Disrupting The Colonial Gender Binary,” 2021.

Chira, “When Japan Had a Third Gender,” 2017.

While it’s theoretically possible, to be able to impregnate someone else and be able to bear a child to term would imply an extremely rare intersex variation; see Bayraktar, “Potential Autofertility in True Hermaphrodites,” 2018.