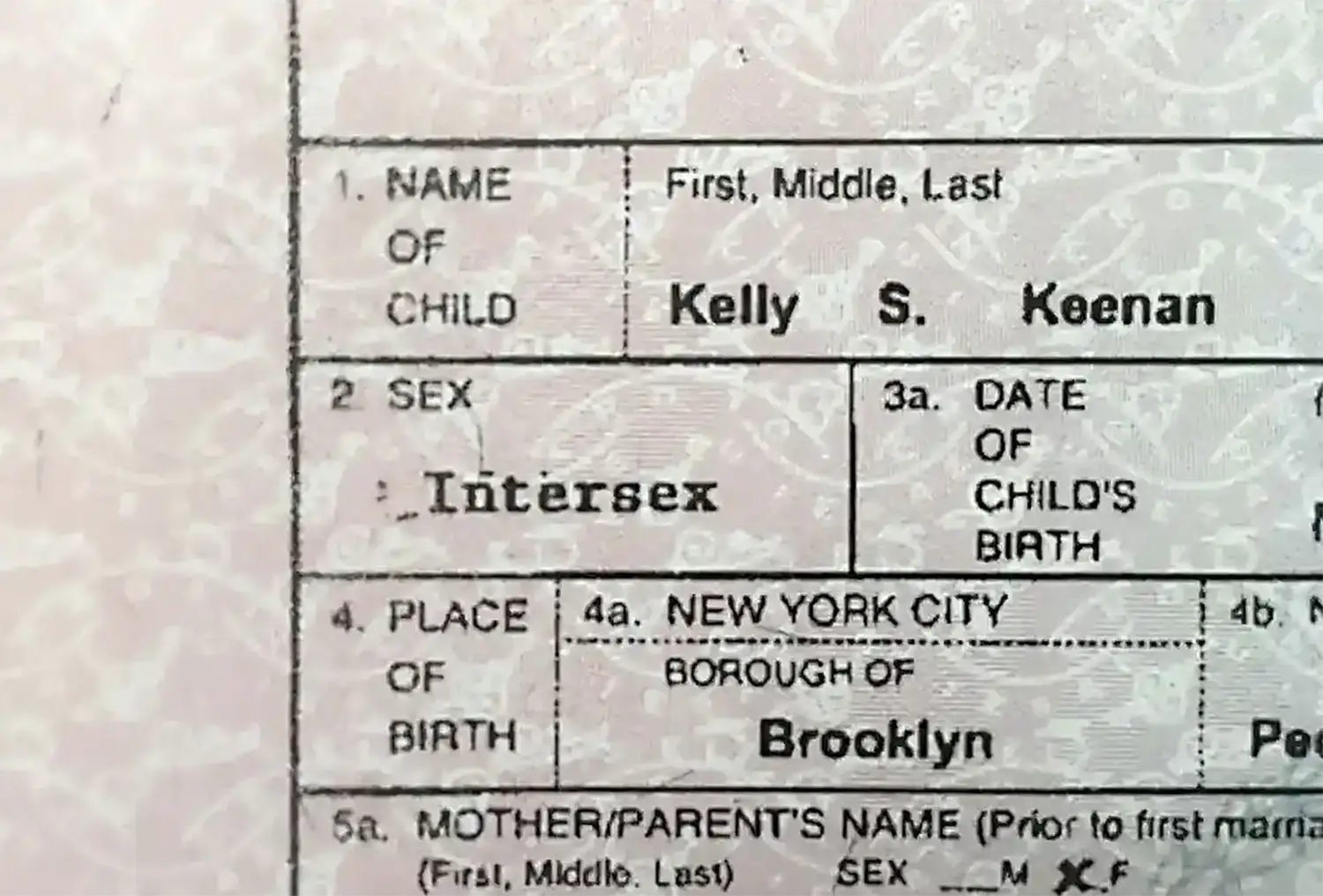

Until recently, “male” or “female” were the only options on US birth certificates, allowing (or compelling) parents to always have a binary answer to that inevitable first question: “boy or girl?” In 2012, Ohio became the first state to formally recognize intersexuality on a birth certificate, and New York followed suit in 2016, 1 but such official recognition remains extremely rare.

The lack of recognition is hard to square with the actual incidence of intersexuality in the population, which the survey suggests is close to 2%—a figure consistent with the medical literature, though the range of estimates is broad due to varying definitions, just as with ambidexterity. The rate of reported incidence is far from constant across ages, though; it rises from barely above 0% at 18 years old to near 2% at age 30 or so, but then drops again to below 1.5% in middle age. At first glance, the finding is puzzling. Making sense of it requires a deeper look at both the biology and the medical history of sex determination.

There’s much more to intersexuality than genital variations, but those are a good place to start, since for many thousands of years the “Boy or girl?” question has been answered within seconds, by visual inspection. For the majority of babies, sex is still determined in a visual snap judgment right after birth, and that determination goes on to influence nearly every aspect of a child’s upbringing and place in the world.

Most people don’t see each other naked too often these days—at least, not in real life. We can stare all day at a parade of fully sex-differentiated adult genitals on the internet, in unlimited numbers and in high definition. Online, sex differentiation tends to exaggeration, featuring unusually large breasts and penises, dramatically developed muscles for men, extreme hip-to-waist ratios for women, hairy parts strategically lush or smoothly shaven, heavily dimorphic faces selectively enhanced with makeup. (Camera angle turns out to be an important hidden variable, as will be discussed in Chapter 14.) In short, the sex binary in most porn is cartoonish, and visibly intersex genitals are exceedingly rare.

It’s unsurprising, then, that most of us have no idea what genitals that are “both,” “neither,” “a combination,” or “somewhere in between” might look like. Of course there is plenty of porn featuring trans people, who may have any combination of vulvas, penises, testicles, and breasts. But these bodies don’t shed as much light on intersexuality as you might think; in fact their penises and breasts, when present, also tend to be highly developed. Trans identity will be explored more deeply in Chapter 12, but for now, suffice it to say that most visibly trans bodies in porn are made possible by modern medicine, often including hormone treatments and surgery, not to mention lucky genes, a careful diet, and lots of time in the gym and at the salon.

Then again, much the same holds for most porn performers, trans or not. It would be optimistic to guess that 1–2% of us look like that with our clothes off. So, intersexuality is both more common than the extreme body types we generally see in porn and, paradoxically, more obscure. Yet intersexuality has been a part of life not only for us, but for every species that reproduces sexually, going back hundreds of millions of years. Shulamith Firestone’s “yin and yang” turn out not to be so sharply defined.

.webp)

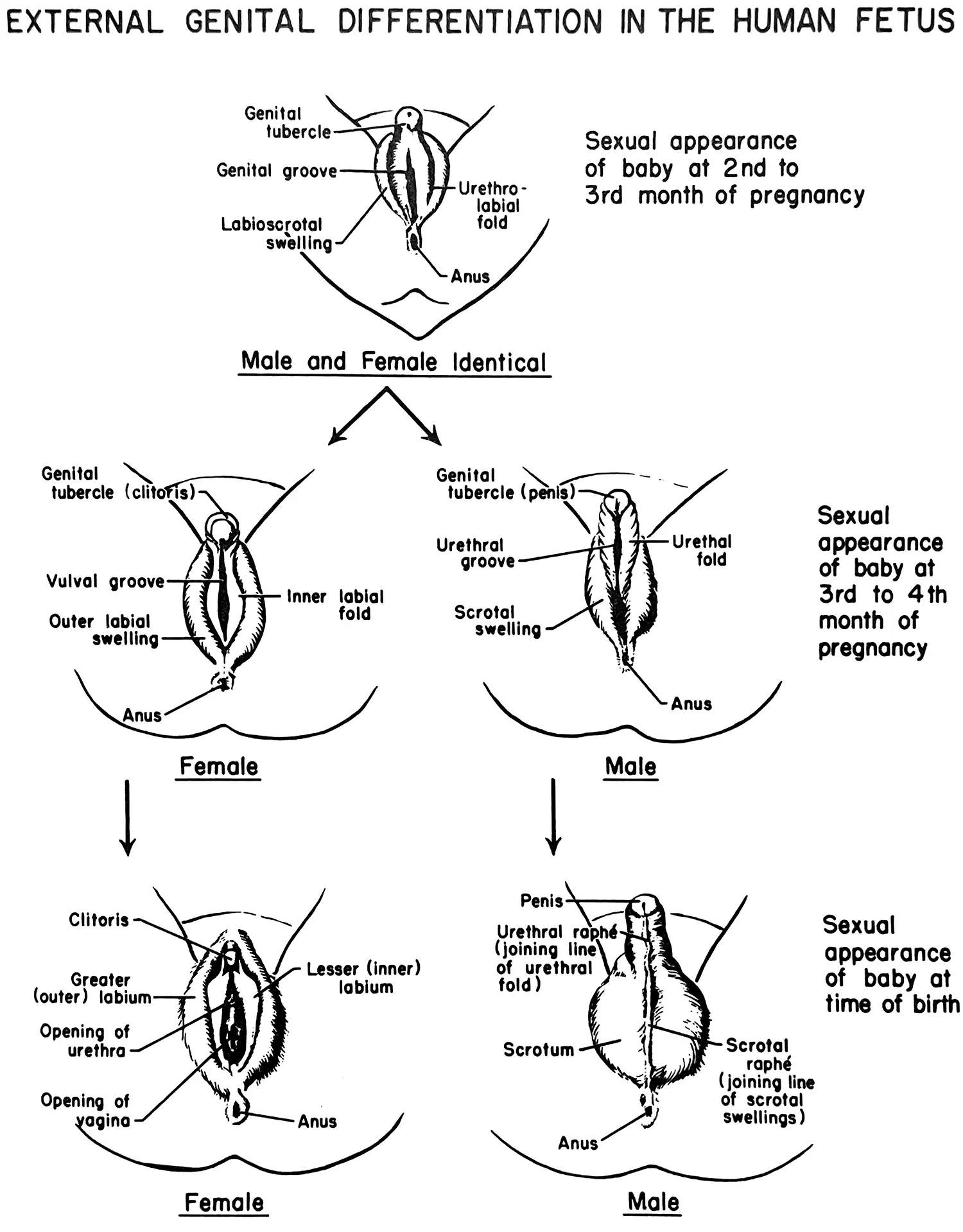

As embryos, we don’t begin with strongly differentiated genitals, but with primordial structures that can develop either way. The ovaries or testicles (or, if undifferentiated, “ovotestes”) start off as a pair of small organs within the abdomen. In female differentiation, a pair of internal structures called the Müllerian ducts develop into the uterus, fallopian tubes, and upper part of the vagina, while in male differentiation the ducts disappear, so that these organs don’t develop—though for those with “persistent Müllerian duct syndrome” (PMDS), the ducts remain, resulting in men with uteruses. PMDS is considered a rare disorder, with only 250 cases documented in the medical literature, but the reality is that we have little sense of how common it is, since the uterus is an internal organ and will only be noticed during medical imaging or surgery. 2 We know that PMDS can cause infertility, undescended testes (meaning testicles that remain in the abdomen), and increased risk of eventual cancer in the uterine or testicular tissue, all of which can motivate imaging and surgery. But an unknown number of cases—and, for all we know, it could be a great majority—don’t lead to these problems, hence may never be discovered.

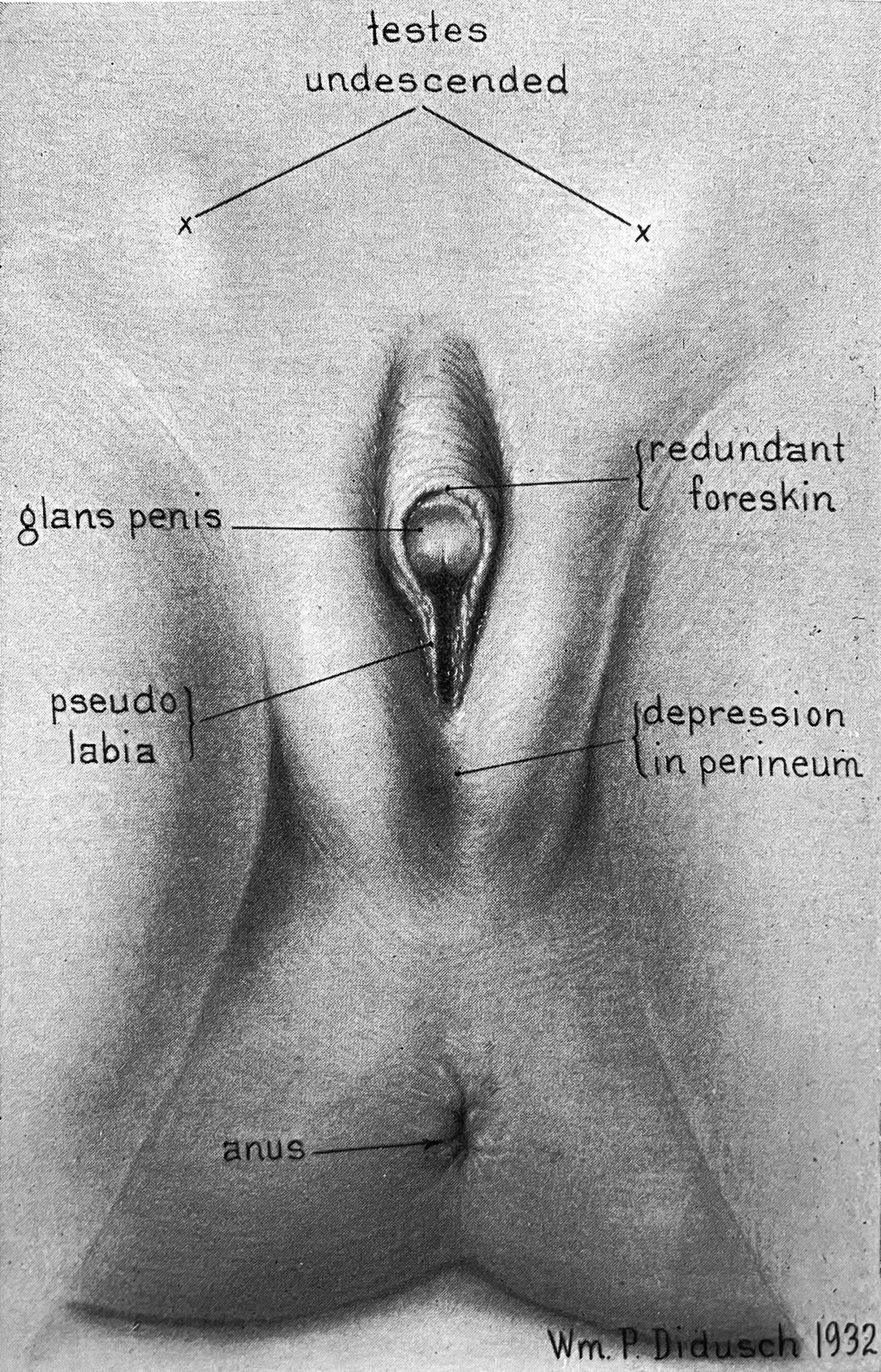

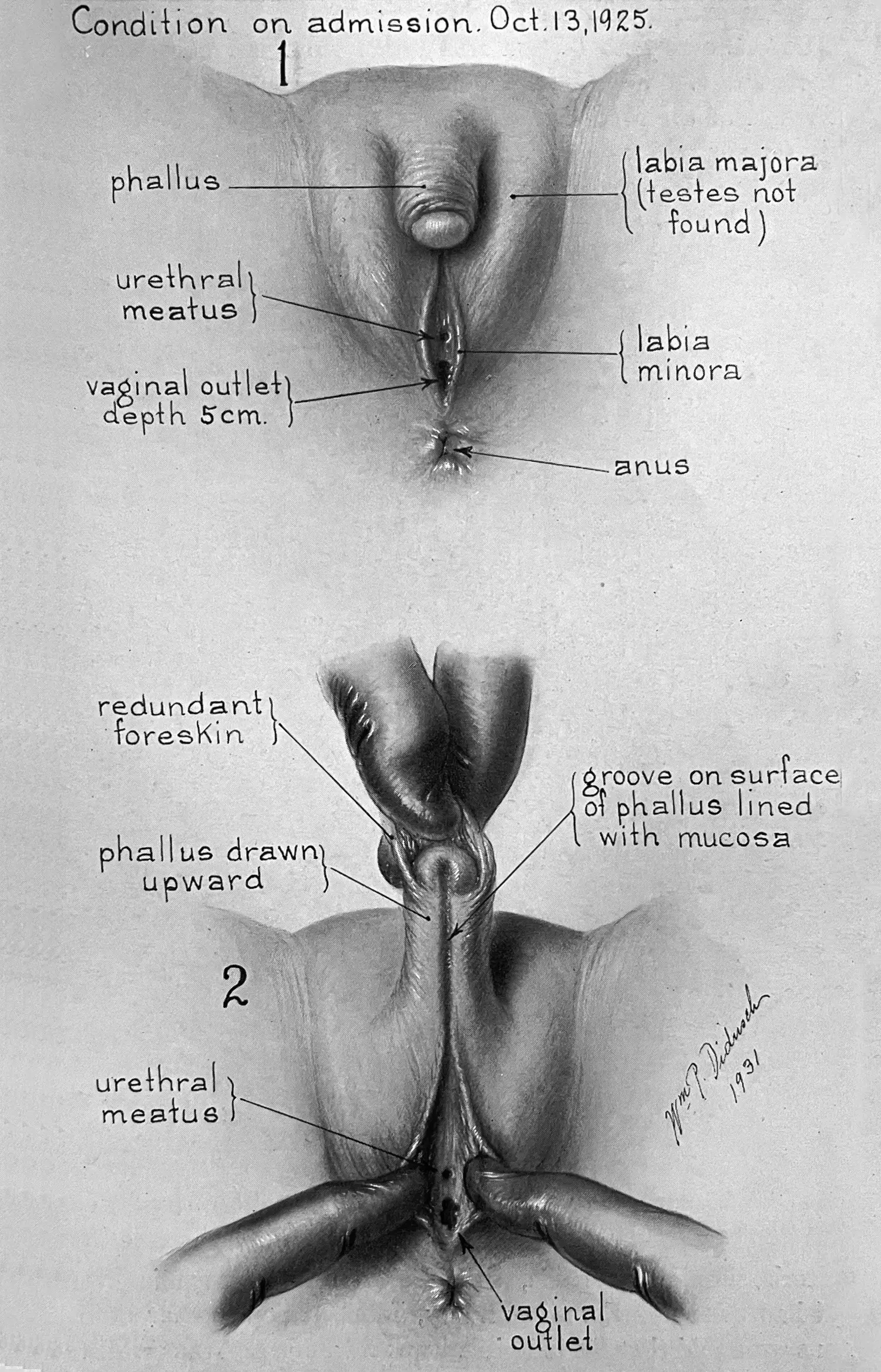

When a variation in fetal development affects the external genitals, it’s harder not to notice. The visible part of the clitoris and the head of the penis are the same structure, but during male development, the inner labia fuse to create the bottom surface of the penis, the outer labia fuse to form the scrotum, and the testes descend into the scrotum. If some of these steps happen but others don’t, or some steps happen halfway, the resulting genitals will vary.

A few different diagnostic tools have been developed over the years to help doctors grade these in-between cases, such as the “Prader scale” and the “Quigley scale.” The latter is shown here. When pediatric endocrinologist Charmian Quigley and colleagues introduced this scale in a 1995 paper, 3 they explained that “Grades are numbered l-7 in order of increasing severity (more defective masculinization)”; grade 1 is “normal masculinization in utero,” grade 2 is a “male phenotype with mild defect in masculinization,” grade 4 is “severe genital ambiguity,” and so on. Such language suggests a value judgment, with the fully differentiated penis as the gold standard and anything else lesser and defective. Is a clitoris really nothing more than a defective and underdeveloped penis?

Before rushing to your own outraged judgment, though, keep in mind that Quigley’s article focuses on one particular set of genetic routes to intersexuality, the Androgen Insensitivity Syndromes (AIS). These involve mutations that cause the body to respond less or not at all to androgens, the key virilizing (meaning, “masculinizing”) hormones during development. Insofar as AIS is considered a medical condition (an analogue would be diabetes caused by insensitivity to insulin, also a hormone), words like “defect” and “severity” make sense—though of course they imply teleology.

People with AIS are in fact genetically male, with XY chromosomes. The real biases in this paper and many others like it are not so much about the superiority of the penis, as about the following assumptions:

sex is naturally binary, hence

intersexuality is a medical disorder, meaning

it should be diagnosed and treated by doctors, and finally

a person’s genes are the ground truth telling us whether they’re “really” men or women. 4

These assumptions are widely held by laypeople too, and reflect the way modern medicine and genetics have influenced popular mental models. The belief that sex and gender are binary (and equivalent) is in keeping with many longstanding religious traditions; as a pious 35-year-old woman from Opelika, Alabama put it,

God is the supreme Ruler and Creator of this world. He gets to make the rules, not us. His order of creation was to form male and female. I’m female. That’s really all there is to it. People are trying to come up with their own “rules” regarding sexuality, and it’s just not our place to do that. Our Holy God is the Sovereign Lord, not us. We get to do things His way, not ours.

Nettie Stevens and Edmund Beecher Wilson independently discovered the XX (female) and XY (male) sex chromosomes in 1905, putting this religious conviction in binariness on a seemingly rational scientific footing. “I’m a male because I have XY chromosomes, and nothing can change that. There are only 2 genders,” per a 36-year-old from Brighton, Colorado. “XX or XY, that’s all there is. The rest is BS,” agrees a 43-year-old man from Dallas, Texas. The idea that genes are inherently discrete or “digital” fits well with human language, which also deals in discrete identity categories like “man” and “woman.” Further, genes are instructions you’re born with, a bit like an inner Bible, or prayer scroll, inscribed in the curled-up genetic code of every cell in your body. Choices, malfunctions, complications, and obfuscations might happen afterward, but your God-given DNA must, so the thinking goes, be ground truth—the original instructions. Per a 36-year-old man from Kissimmee, Florida,

While I do not support any discrimination against LGBT or any other life choice people make, and respect any identity someone decides to claim as their own, the fact is that gender is not a social construct. There is a huge amount of variety to human beings, but “male” and “female” are scientific designations that involve the number of chromosomes one has, and someone’s biological origin cannot be changed. Leave people to do as they wish as long as it is not hurting anyone, but at the same time, don’t ignore science and common sense.

So, does DNA always tell us whether someone is a man or a woman? Firstly, there are a number of fairly common viable chromosomal variations other than XX and XY, including XXX, XXY, and XYY, X0 (only an X chromosome), and rarer variations like XXXY, XXYY, XXXYY, and so on. Many people with these variations have intersex characteristics.

But this is just the tip of the iceberg.

I found a curious short comment among the survey responses from a 61-year-old man: “chromosomal mix, xx and xy. fusing of fraternal twin eggs.” This remarkable phenomenon is called chimerism, after the chimera of Greek mythology, an imaginary creature composed of the parts of other animals (traditionally, a lion’s head, a goat’s body, and a serpent’s tail). The survey respondent was originally a pair of twins in the womb, each a different egg fertilized by a different sperm cell, which fused early in development to form a single fetus. In such cases, there’s a 50% chance that the fused fraternal twins won’t be the same sex, as happened here. In adulthood, each of his body’s cells has a lineage tracing back to one or the other embryo, so genetically, his body is a mosaic of male and female cells! How those cells are distributed throughout the body depends on the timing and details of the fusion. In some cases the result is a sharp boundary between the left and right halves of the body; in others, cell lineages cluster in patches or in whorls.

Chimerism is possible for any multicellular organism, including plants. Many calico or tortoiseshell cats are chimeras. So-called gynandromorphs, half female and half male, are especially striking in animals that are more sharply sexually dimorphic than humans—that is, where the sexes differ dramatically in size or coloration, as with peacocks and pea hens, or butterflies.

Like PMDS, chimerism in humans is supposedly very rare; there are only about a hundred documented cases. 5 Singer-songwriter Taylor Muhl is one. To raise awareness of the condition, she has posted selfies on social media showing the striking change in coloration between the left and right sides of her abdomen, revealing the different genetic origins of those cells.

If chimerism in humans were really so rare, it would be remarkable luck for one of these near-mythical people not only to have taken my gender survey, but also to have thought to write about their chimerism in the comment field. But wait: a second such individual responded too! She’s a 26-year-old from Stafford, Texas:

FAAB, 6 woman in gender, born with chimeric teste in place of right ovary. I like to joke I ate my twin brother in the womb. I’ve named this prototeste Conrad the Gonad.

It’s hard not to conclude that the real rate of human chimerism must be far higher than those 100 documented cases suggest, especially since, again like PMDS, the great majority of chimeric people are unlikely ever to find out that they’re chimeric, and only half of those with chimeric genes will be gynandromorphic. It’s not possible to pin down a real frequency for chimerism from the survey data, but I’d guess that 1 in 1,000 is a better order of magnitude estimate than the “almost never” one would naïvely get by dividing the 100 documented cases by the world population.

All of which is to say that even if one were to assume that genes were the ground truth for sex—and there’s good reason to doubt this—many more chromosomally ambiguous cases exist than one would think, because quite a few people are walking around with some cellular mixture of Conrad the Gonad and his twin sister.

Intersexuality poses an even more fundamental challenge to the idea of sex being binary in the first place, or being determined by chromosomes. The biological and social machinery of sex and gender differentiation is just complicated; it has many moving parts and feedback loops, all of which can vary from person to person to produce different results. For instance, everybody with an Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome is genetically male, including people with complete insensitivity (grade 7 on the Quigley scale), most of whom are—by their account and pretty much everyone else’s—obviously women. Their bodies look female at birth, they are raised as girls and grow into women, and indeed many will never learn that they don’t have uteruses or a second copy of the X chromosome in their cells. Those discoveries typically only take place if they decide to have children, try for a while, and ultimately go to a fertility clinic to understand why they aren’t conceiving. (Note, also, that this implies wanting children and either living in a country with socialized medicine or belonging to the kind of upper middle class milieu where visiting the fertility clinic is a done thing.)

At the clinic, they will learn that they’re sterile. Of course this won’t suddenly render them “not women,” any more than a hysterectomy would. But they will also now know that they’re intersex. Doctor’s visits like these are almost certainly why positive responses to “Are you intersex?” rise from near zero to a high water mark during the years between 18 and thirtysomething. After menopause, of course, the odds of finding out will decline.

There’s every reason to believe that, insofar as it’s meaningful to talk about a “real” rate of intersexuality, it’s even higher than the survey’s numbers suggest. A 24-year-old woman from Monroe, Louisiana, wrote, for instance, “Sometimes I wonder if I’m genderfluid or intersex, but I’m not confident enough in the former and have never been tested for the latter.” A 25-year-old woman from Bella Vista, Arkansas, wrote in more detail about her experience, which is far from uncommon:

I don’t consider myself trans-anything, but I’ve always been fairly ‘masculine’ in my attitude, interests, desires and the way I express emotions (though I do have a feminine side). I suspect I have hormone problems, which gave me facial hair and makes me feel very unattractive as a female. I think I’d probably make a better guy because then maybe people wouldn’t notice the hair, but I don’t really ‘want’ to be a guy. I just don’t want to be an anomaly.

The fact that almost nobody grows up knowing they’re intersex, but some may then find out they are in a doctor’s office later in life, goes some way toward explaining the continuing invisibility of intersexuality. Since it’s widely understood as a medical diagnosis, being intersex tends to fall under the veil of privacy reserved for medical matters. It’s not anyone else’s business. Intersex people may seek out support groups, but they’re unlikely to “come out” to friends, family, or colleagues, let alone adopt intersexuality as an identity, especially if (as is often the case) they feel themselves to be men or women, and present that way to others too. In some cases, that feeling is unambiguous. In other cases, it isn’t, but there’s often a desire to “pass” anyway. As a 23-year-old man from Port Huron, Michigan, wrote, “intersex people don’t want recognition, it puts a huge target on us for abuse.”

Unfortunately this secrecy perpetuates the stigma surrounding intersexuality, as well as the mistaken belief on the part of most people that it’s vanishingly rare (if they’ve even heard of it). At roughly 2%, being intersex is at least as common as having red hair. Almost certainly, you know intersex people. However, very likely, you don’t know you know them.

It’s widely assumed that intersexuality is lifelong, and that it crops up at some constant rate—some fixed number of births out of every thousand. These assumptions are reasonable, but let’s hold them only tentatively. For one thing, definitions may be too slippery for any single number to be objectively correct, or to remain constant as our understanding evolves. Also, mounting (though still inconclusive) evidence points to environmental factors altering the odds over time.

Studies have found, for example, that estrogen-mimicking compounds in wastewater have been both changing the sex ratio and increasing the numbers of feminized intersex frogs in suburban neighborhood ponds. 7 Something like that could be happening to humans too. It’s one of many ways our reshaping of the environment seems to be coming back around to reshape us in a feedback loop of unintended consequences.

Setting this speculation aside, though, let’s suppose that people at all times and of all ages have an equal probability of being intersex. If so, the large variability in responses to “Are you intersex?” by age is presumably a function of how many people know they’re intersex, as opposed to how many of them actually are.

The real number of intersex people is then at least as high as the peak of this curve, near 2%. (The incidence probably is higher still, since surely fewer than 100% of intersex 29-year-olds know that they are.) You might suppose older would mean wiser, but from age 42 onward, only about two thirds as many people seem to know as at age 29.

Why does the percentage of people who know they’re intersex drop among the older population? Presumably they haven’t forgotten! The decrease most likely reflects evolving attitudes and practices regarding intersex births, and these changes may have far-reaching implications. To understand them, let’s return once again to the 19th century.

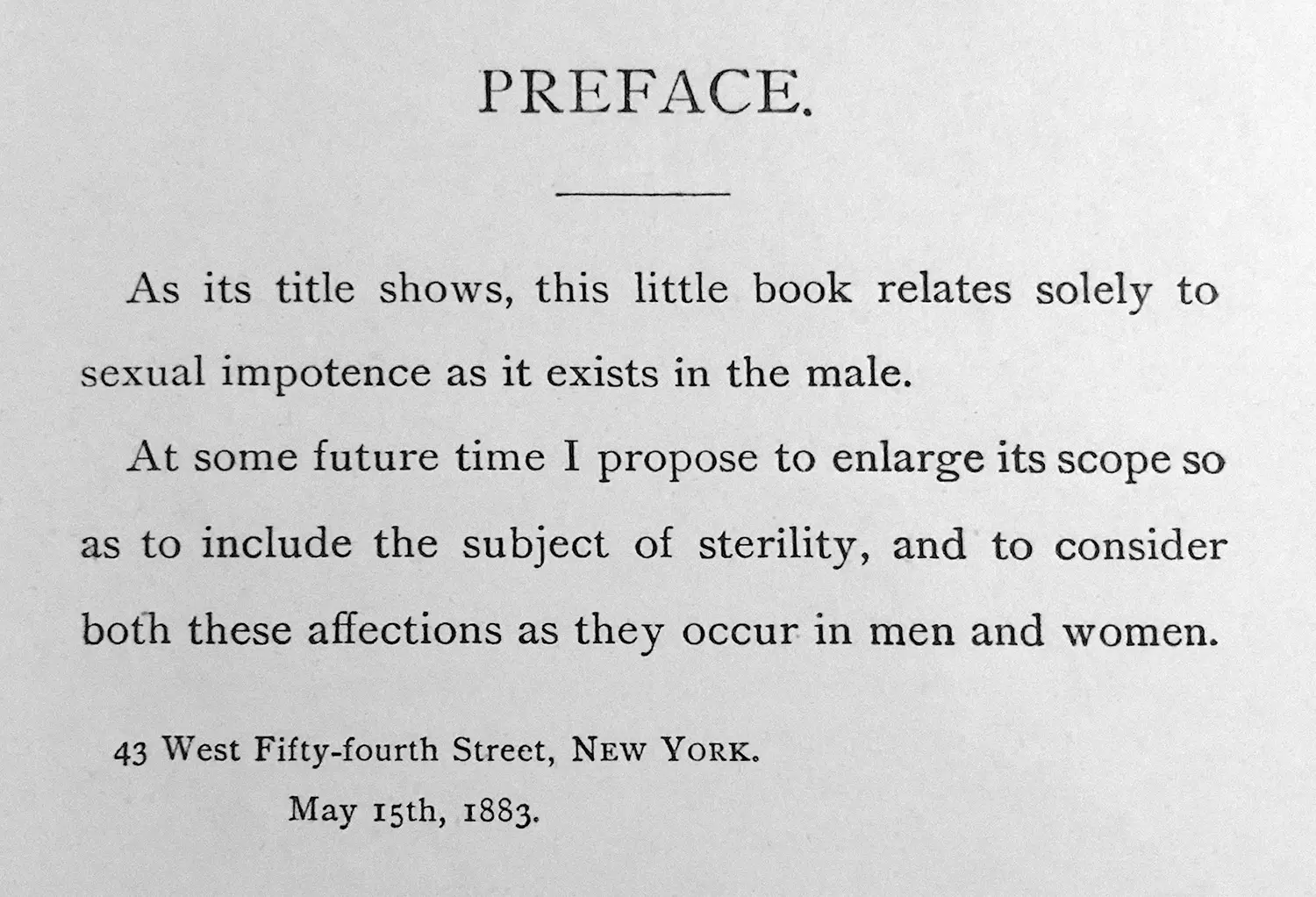

In 1883, before the genetic basis of sex was understood, US Army Surgeon General William Hammond published a book called Sexual Impotence in the Male. In case the title wasn’t clear enough, he noted in the preface that the book “relates solely to sexual impotence as it exists in the male,” adding that he might later enlarge it to “include the subject of sterility, and to consider both these affections [disorders] as they occur in men and women.” 8 But in describing congenital presentations of the genitals that could result in “sexual impotence in the male,” he covers a number of cases we now understand to be intersex. Hammond variously describes Quigley’s grades 2 through 4, for example, as “hypospadias” and “suture of the penis.” 9 He also describes the absence of testicles, or undescended testicles, and a tendency in some such cases to assume “in many respects the mental and physical attributes of the female sex.” 10

Interestingly, this kind of characterization views nearly every part of the excluded middle as a defective kind of masculinity—just as the Quigley scale would in the next century. While some of Hammond’s case studies were probably people with XY chromosomes and an Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome, others were likely people with XX chromosomes and a different set of genetic variations leading to virilizing effects, such as Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH)—which is also considered rare but, as with the other conditions mentioned earlier, is likely underreported. Perhaps in the near future some high tech national health system will begin doing full genetic sequencing of all newborns; only then (chimerism aside) will we really know.

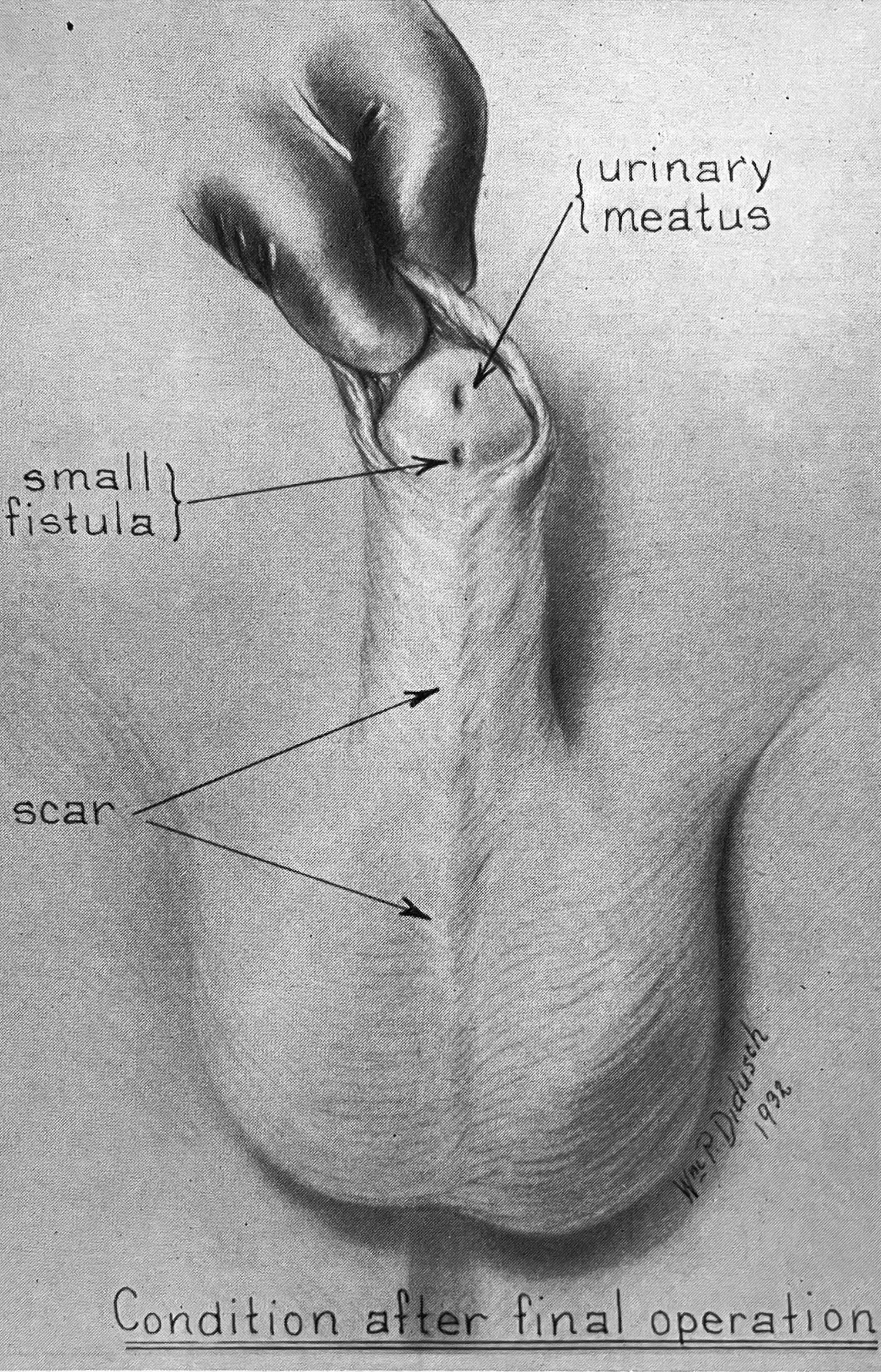

In any event, when a (usually male) doctor in the late 19th or early 20th century delivered a baby with genitals that looked like a Quigley 2 or 3, the verdict was invariably “it’s a boy,” with the caveat that cosmetic plastic surgery might be needed to render the baby more “normal looking,” not unlike a cleft lip or palate. “Hypospadias surgery” could be quite minor, little more than a bit of sewing up of what would become the lower surface of a penis.

Throughout the 20th century, surgery became increasingly sophisticated and doctors came to better understand the role of hormones in sex differentiation. Administering hormone therapies to either virilize or feminize babies and children became possible. This made it increasingly straightforward to treat many intersex births as boys whose penises simply needed a bit of surgical and hormonal “help” to develop “properly.” It was an age of… medical cockiness.

For intersex babies on the far right end of the Quigley scale, though—regardless of chromosomes or other factors—no matter how hard the doctors squinted, they couldn’t see a penis. Instead, they saw an oversized clitoris, or “cliteromegaly.” And as a 1963 article on intersexuality explains, “In border-line cases with hypertrophy of the clitoris, amputation of the clitoris may be necessary for cosmetic reasons.” 11 So, a century after Acton’s enthusiastic endorsement of surgical removal of the clitoris to deny women pleasure, doctors were still keen on cutting off clitorises—but now just for appearance’s sake.

It’s telling that upon deciding a baby was female, “normalizing” the way the genitals looked took precedence over any sexual pleasure they might provide. 12 One can’t help wondering whether the conclusion would have been the same if a similar procedure were needed to conform to “normal” male appearance? For girls, removal of the clitoris might be a necessary aesthetic sacrifice, but for boys, as we’ll soon see, removal of the penis was an unthinkable tragedy. 13

In cases of so-called testicular feminization (today referred to as Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome), the 1963 article goes on to recommend that children be

[…] brought up as females in spite of their male gonads and chromosomal sex. They should never be told they have testes, or that they are hermaphrodites, but we always do explain to them that they are sterile, and will remain so, and that they will never menstruate. Usually they accept this knowledge very well. Most married women either adopt children or take part in extra-household activities which they often pursue with great success because of their above average intelligence. 14

Passages like these are rife with the biases that pervaded medicine’s approach to gender in the 20th century. For one, the throwaway comment about “above average intelligence” is based on the notion that the XY chromosomes would, despite any outward appearance of femininity, result in a more “male,” hence more intelligent, brain! 15

Setting this eye roller aside, the article’s advice to doctors sheds further light on why young people who are intersex almost never know they are. Standard practice for doctors delivering an intersex baby was to make a measurement with a ruler and, based on clitoris/penis size, decide whether to “sew them up” and (sometimes) administer virilizing hormones, or amputate and (sometimes) administer feminizing hormones. 16 This was all done as young as possible, ostensibly in order to avoid exposing the child to any gender ambiguity growing up—either in their family relationships or in their underwear.

The results could be devastating. In the 1990s, sex activist Annie Sprinkle wrote,

In my last workshop, we had a woman who was born with hermaphroditic genitals. At one and a half years old, the surgeons mutilated her. They removed her penis, which was really an enlarged clitoris, and her inner labia. Now she has horrible vaginal and psychological pain, and has never experienced orgasm. […] She’s very angry about having been mutilated, so now she’s organizing other people like herself through a newsletter. Unfortunately, this is very common, but rarely addressed. People who are not stereotypically male or female suffer so much. 17

Ironically, these practices were based on an idea that seemed progressive in the postwar years: that gender was not innate or biologically predetermined, but was rather an emergent phenomenon, constructed socially and psychologically. The ideological pendulum had swung from pure nature to pure culture.

Scutti, “‘The Protocol of the Day Was to Lie’: NYC Issues First US ‘Intersex’ Birth Certificate,” 2016.

“Persistent Müllerian Duct Syndrome,” 2021, link.

Quigley et al., “Androgen Receptor Defects: Historical, Clinical, and Molecular Perspectives,” 1995.

Especially in his later work, Quigley himself expressed a more nuanced take, e.g. in Liao et al., “Determinant Factors of Gender Identity: A Commentary,” 2012.

Wolinsky, “A Mythical Beast. Increased Attention Highlights the Hidden Wonders of Chimeras,” 2007.

Female Assigned At Birth.

Lambert et al., “Suburbanization, Estrogen Contamination, and Sex Ratio in Wild Amphibian Populations,” 2015.

Hammond, Sexual Impotence in the Male, 1883.

Hammond, 220–21.

Hammond, 247.

Hauser, “Testicular Feminization,” 273, 1963.

John Money, soon to be introduced, argued for “no evidence of a deleterious effect [on erotic sensation] of clitoridectomy,” based on the reported experiences of a dozen women with CAH who underwent the procedure at an older age and consensually. Money, Venuses Penuses: Sexology, Sexosophy, and Exigency Theory, 144, 1986. There are, however, some obvious reasons to treat this assertion with a grain (or more) of salt.

Similarly, John Harvey Kellogg might have gotten away with cutting off the foreskins of boys who were caught masturbating one too many times, but he certainly couldn’t have gotten away with cutting off the whole thing.

Hauser, “Testicular Feminization,” 273, 1963.

A couple of contemporary studies attempted to prove this rather dubious assertion, but they wouldn’t pass muster by any modern evidentiary standard. Chapter 15 will offer a more informed perspective.

Springer, van den Heijkant, and Baumann, “Worldwide Prevalence of Hypospadias,” 2016; Keays and Dave, “Current Hypospadias Management: Diagnosis, Surgical Management, and Long-Term Patient-Centred Outcomes,” 2017.

Brown and Novick, Voices from the Edge: Conversations with Jerry Garcia, Ram Dass, Annie Sprinkle, Matthew Fox, Jaron Lanier, & Others, 38, 1995.