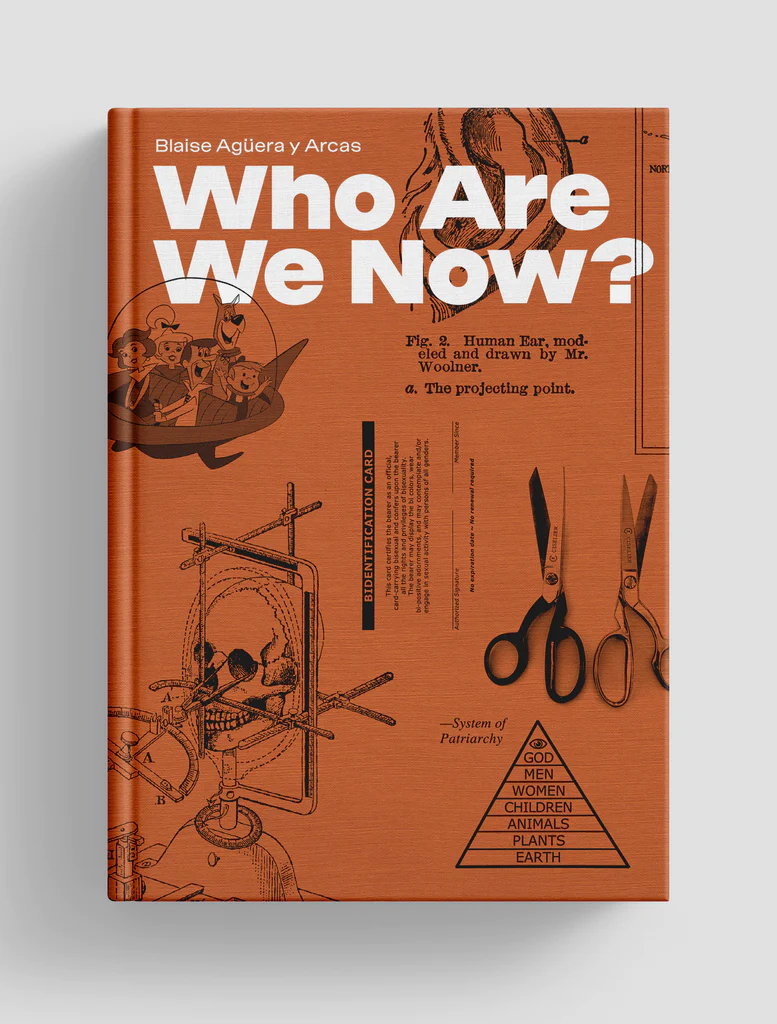

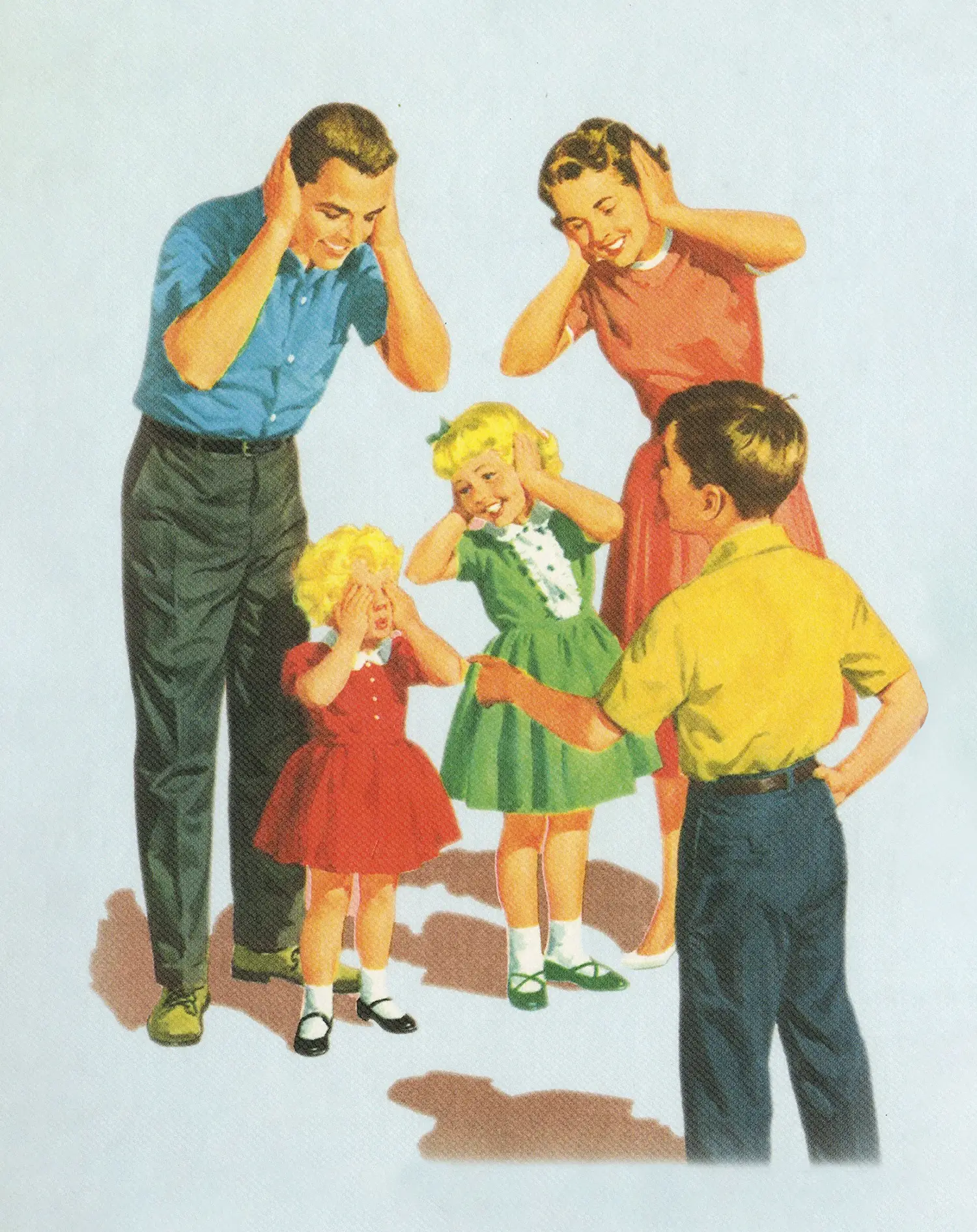

This is a book about human identity: the frontline in today’s culture wars. The book’s backbone consists of a set of surveys I conducted between 2016 and 2022, asking tens of thousands of anonymous respondents all over the United States simple, at times intimate, questions about their identity and behavior, and especially about gender and sexuality. The surveys open a window into people’s lives a bit like the one opened in the middle of the 20th century by sex researcher Alfred Kinsey and his collaborators. Their wonky, questionnaire-based reports scandalized postwar America. Though methodologically flawed, the Kinsey reports correctly concluded that, to use today’s language, people were a lot queerer than had been assumed, and less easily categorized. Cracks were showing in the façade of the white, middle-class, heterosexual “normalcy” on display in popular media—Dick and Jane in the 1950s, the Flintstones and the Jetsons in the 1960s, the Brady Bunch in the 1970s.

By the 2020s, it has become clear not only that the cracks have widened, but that the whole edifice was an artifact of its historical era, long gone. We’re living in a different world now, and probably, under the social surface, we always were. Sex and gender are complicated. Suppressing their complexity with received moral wisdom about what is and isn’t “natural” has become increasingly untenable. Young and urban people, especially, are not buying it.

But what motivated me to conduct these surveys? My own gender, sexuality, and family life are unremarkable, even by last century’s standards. Neither am I a sexologist, sociologist, or anthropologist. I work on artificial intelligence at a big tech company, which on the face of it seems unrelated. Digging a bit deeper, though, the rapid advance of AI has forced my colleagues and I to think hard about humanity. How do we envision our future? Who are “we,” anyway? Does we include collective identity groups as well as individuals? Nonhuman animals and plants? Governments and corporations? Will it soon include robots?

Such questions are far from academic. Regarding the last, for instance: computers have become enmeshed in our personal lives, moving in just a few years from being office furniture to living in our purses and pockets, mediating our most intimate relationships. The intersection of AI and privacy, one of my team’s main areas of research, has thus become an urgent concern. Beyond that, computers are starting to look less like tools than like extensions of our bodies and minds, always on and always connected, as if telepathically. Online, our presentation can become increasingly decoupled from our physical selves. Neural nets are now able to model human language and interact with us on our own terms, which will soon lead to all sorts of novel human-AI relationships. What kind of strange hybrid world will our kids grow up in?

EDIT.webp)

It’s telling that “the future” and “our children” seem like phrases joined at the hip. Their association, suffused with nurturing, protective values, has sometimes been called reproductive futurism. 1 It’s hard to argue against being “pro child,” especially if the alternative sounds selfish, uncaring, or short-sighted. Children are sweet, and we hold them in a state of grace, because they either haven’t had the chance yet to make truly bad choices, or they aren’t old enough to take full responsibility for them. 2 For obvious evolutionary reasons, many of us are powerfully compelled to nurture and protect them, especially when we believe they’re “ours”—which might mean nationally or tribally, and can of course include adoption, but most often means genetically. In this sense, reproductive futurism is bound up in heterosexuality, in having and raising kids who will propagate our genes—and in the old days, the more the better.

Increasingly, though, it’s becoming clear that for civilization on our planet to survive, we need fewer kids, not more. This isn’t about curtailing our future, but about embracing it. Civilization comprises far more than the sum of its human reproductive lineages; it’s about our relationships with one another, the knowledge and cultures we’ve built up over thousands of years, our institutions, our cities and our countryside, our sciences and technologies, our languages and our art.

This implies a shift from reproductive futurism to something more like ecological and civilizational futurism. The shift implies that gender and sexuality have a different role to play now, with biological reproduction no longer center stage—which is precisely what we see happening. Is that a coincidence? Queer and trans identities are rapidly on the rise. Nontraditional relationships of all kinds are becoming far more common too, and many of them aren’t focused on making babies. Even for young people who are heterosexual and fairly traditional, the likelihood of marrying and having kids is in sharp decline worldwide, especially in cities and in the more economically developed countries. 3

Not everyone is happy with these changes. One of the more traditionally minded survey respondents wrote, “all these homos will burn in hell. What would happen to a animal species that went gay, I’ll tell you, they would all go extinct… bunch of dipshits.” 4 Birth control and access to abortion have of course played a much larger role in the shift than “going gay,” so unsurprisingly, these practices, too, have become flashpoints in the culture wars. Meanwhile, despite (or perhaps, partly, because of) ubiquitous connectivity, loneliness and isolation have become endemic, both in small towns with dwindling populations and in increasingly anonymous big cities. Sexuality itself, both partnered and solo, seems to be in decline. 5 Is this the way we’re meant to live?

At their core, the culture wars are about who we are now, how we define what’s “natural” and whether that’s actually desirable, and to what extent we can redefine ourselves over time without becoming something entirely unnatural, alien… other. Since everyone alive today would likely seem thoroughly alien to a paleolithic human, perhaps our cultural divide is about differences in people’s maximum comfortable rates of change.

Consider, for example, how the struggle to define and delimit humanity in some elusive “natural” state animates a long-simmering debate about the Olympics. Such high-stakes physical competitions are fraught with contradiction, in that they harness human ingenuity and our capacity for self-modification to select for and continually expand the limits of what bodies can do. Somewhat arbitrarily, caffeine and high altitude training are allowed, but blood doping 6 and steroids are not.

Meanwhile, the Paralympic games, originally a gesture toward greater human inclusivity, have turned the tables. Paralympians with prosthetics are now beating Olympians at running, and as technology improves, they’ll doubtless do so in other events too. Where do we draw the line? Decisions to allow or prohibit specific technologies will come to look increasingly absurd—as will decisions to allow or prohibit people, or to classify them “fairly.”

For instance, in order to allow women to compete meaningfully as runners, their events have been segregated from the men’s since the early 20th century; yet doing so made it likely that people with intersex characteristics would rise to the top of certain women’s events. 7 Over the years, committees were then put in place to attempt to rigorously define and enforce sex boundaries—a practice, this book will argue, that is not only humiliating for athletes, but downright impossible. 8 Similar controversies have broken out on a much more local scale over trans kids competing in gendered school sports programs. At some point, we’ll need to admit to the futility of trying to police categories like women versus men, or natural versus augmented. We’re all augmented in so many ways—physically, intellectually, and societally.

On optimistic days, I imagine natural systems, together with blended human and machine intelligence, converging into something smart, intentional, and planet-wide. I don’t think of AI and human intelligence in opposition, or of one as subservient to the other in some kind of medieval Chain of Being; rather, I think that all intelligence on Earth is part of a larger whole, and that individual freedom and grand collectivity are compatible.

I hope that we can think and act soon on a planetary scale, because the great challenges we now face are all planetary in scale too—and largely of our own making: climate collapse, pollution, pandemics, loss of habitable land, surging inequality, desperate mass migrations. We live in the Anthropocene, a geological era defined by human activity.

We’ve gotten into this pickle thanks to the advanced technologies civilization has developed over thousands of years, enabling us to explode in numbers, burn fuels, and consume resources far in excess of what can be sustained. It’s not just human bodies that are burning and consuming too much, but cows, factories, jet engines, and crops—a multispecies, cyborg lichen whose reach has, for the moment, exceeded its grasp. Major changes will be needed—and they are possible, with ideas and partial solutions already glimmering here and there. Our challenge is that while our technologies may be products of our collective imagination, our actions, our will, and the ways we identify are still not collective enough.

Edelman, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive, 3, 2004.

Legally, this is the very definition of childhood.

Kulu, “Why Do Fertility Levels Vary Between Urban and Rural Areas?,” 2013; Ortiz-Ospina and Roser, “Marriages and Divorces,” 2020; Roser, “Fertility Rate,” 2014.

A 33-year-old man from Kalamazoo, Michigan. When quoting survey respondents, I’ll usually do so verbatim, neither correcting spelling and grammar nor adding the obnoxious “[sic]” disclaimer.

Herbenick et al., “Changes in Penile-Vaginal Intercourse Frequency and Sexual Repertoire from 2009 to 2018: Findings from the National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior,” 2022.

Meaning: taking drugs or getting transfusions to increase an athlete’s red blood cell count.

Intersexuality is a complex topic, discussed in Chapters 11-13 of this book. Women with certain intersex variations have elevated androgens, which are strongly correlated with elite athletic performance; see Bermon et al., “Serum Androgen Levels Are Positively Correlated with Athletic Performance and Competition Results in Elite Female Athletes,” 2018 and Bermon and Garnier’s “Serum Androgen Levels and Their Relation to Performance in Track and Field: Mass Spectrometry Results from 2127 Observations in Male and Female Elite Athletes,” 2017.

Jensen, Schorer, and Faber, “How Is the Topic of Intersex Athletes in Elite Sports Positioned in Academic Literature Between January 2000 and July 2022? A Systematic Review,” 2022.