The central themes of this book have all revolved around human identity: how we think of ourselves and others, how we form communities, and how we propagate through time. Answering the question “Who are we now?” requires us to reflect on a more basic question: Who do we mean by “we”?

In her book Twilight of Democracy, Anne Applebaum emphasizes the urgency of both questions given the recent worldwide turn toward authoritarianism—even in countries, like the US, whose democratic institutions seemed solid at the close of the 20th century. Whether they arise from the political right or left, authoritarian leaders and their enablers invariably weaponize identity politics in the service of us-versus-them nationalism. We’ve seen how urbanization, especially in countries open to immigration, can create politically polarizing feedback loops that pit cities against rural communities. Yet at a party she threw in the Polish countryside for her friends, both left- and right-leaning, younger and older, Applebaum noticed the

[…] false and exaggerated division of the world into “Somewheres” and “Anywheres”—people who are supposedly rooted to a single place versus people who travel; people who are supposedly “provincial” versus those who are supposedly “cosmopolitan” […]. [P]eople with fundamentally different backgrounds could get along just fine, because most people’s “identities” stretch beyond this simple duality. It is possible to be rooted to a place and yet open to the world. It is possible to care about the local and the global at the same time.

Applebaum felt especially hopeful about the young:

They mixed English and Polish, danced to the same music, knew the same songs. No deep cultural differences, no profound civilizational clashes, no unbridgeable identity gaps appeared to divide them. Maybe the teenagers who feel both Polish and European, who don’t mind whether they are in the city or the country, are harbingers of something else, something better, something that we can’t yet imagine. Certainly there are many others like them, and in many countries. 1

The data in Chapter 16 support Applebaum’s view. Young people from the city and from the countryside are far more alike in their outlook than older people. Technology, double-edged as always, can take both credit and blame—credit for connecting far-flung people together into global communities (especially the young), and blame for enabling the mass surveillance, disinformation, and polarization campaigns that empower authoritarianism and create social division.

The social challenges posed by driverless cars 2 suggest that technology will soon have an even more profound role to play in our answer to the question “Who are we now?” AI enables machines to exhibit agency, and as such, requires us to think of them as more than mere “engines” performing rote computational tasks, or passive “media” helping humans to communicate at a distance. Our reluctance to imagine that anything nonhuman could exhibit agency has far deeper roots than the AI debate; it has much to do with how Western thought has conceived of the nonhuman natural world as an “externality,” that is, as also lacking agency.

I believe that “we” ought to expand to include not only the nonhuman life on our planet, but also all of its factories, tools, and robots—that they are no less “natural” than the farm, or the forest, or our own human bodies. James Lovelock, of Gaia hypothesis renown, 3 agreed:

[N]either Newcomen’s [steam] engine nor a nuclear power plant looks or behaves much like a zebra or an oak tree; they appear to be utterly different in every respect. Nevertheless […] the Anthropocene is a consequence of life on Earth. It is a product of evolution; it is an expression of nature. 4

As a wise systems thinker, Lovelock was alive to the way ecosystems are built out of webs of interdependence. Technology is no exception:

We shall not descend into the kind of war between humans and machines that is so often described in science fiction because we need each other. Gaia will keep the peace.

This isn’t a plea for granting personhood as usually understood, with its attendant rights and responsibilities, to giant yellow FANUC robots and autonomous John Deere tractors. Nor does it make sense to ask squirrels and rivers to vote in our elections. We’re having a hard enough time securing human rights (and the vote) for all humans! Soon enough, we probably will have robots with something akin to feelings, consciousness, and a sense of self we can relate to socially, and this will inevitably complicate our thinking, but that’s a topic for a whole different book. In any case such questions about personhood, social status, and agency seem irrelevant for the kinds of robots described in Chapter 20—asocial machines that do intensive, repetitive life support labor far away from human beings, on farms, at ports, and in production lines. We probably don’t need to discuss robot rights for irrigation systems.

However, the habit of “othering,” which we’ve encountered so many times throughout this book, is troubling both when we apply it to each other, and when we apply it to nature or technology. It’s not coincidental that in this period of increasingly fractious identity politics, many of us are also distancing ourselves from our own technologies—asserting that they’re separate from us, or even at odds with us, rather than an integral part of who we are. 5 Intersex surgeries, hormone therapies, birth control, in vitro fertilization, and other medical technologies of the postwar era have been key to the emergence of many of the identities explored in Part II. 6 Technology has allowed us to emancipate ourselves from the Malthusian trap of subsistence agriculture, and has enabled us to start dismantling the patriarchy that has accompanied it. 7 The technologies that allow large cities to form have been prerequisites for the rich cultures and minority identities that emerge in urban conditions, as Kinsey pointed out and the survey data confirm. 8 And, of course, most of us wouldn’t exist at all had it not been for the technological revolutions that so dramatically increased our numbers starting around 1700, and stepping up further around 1945.

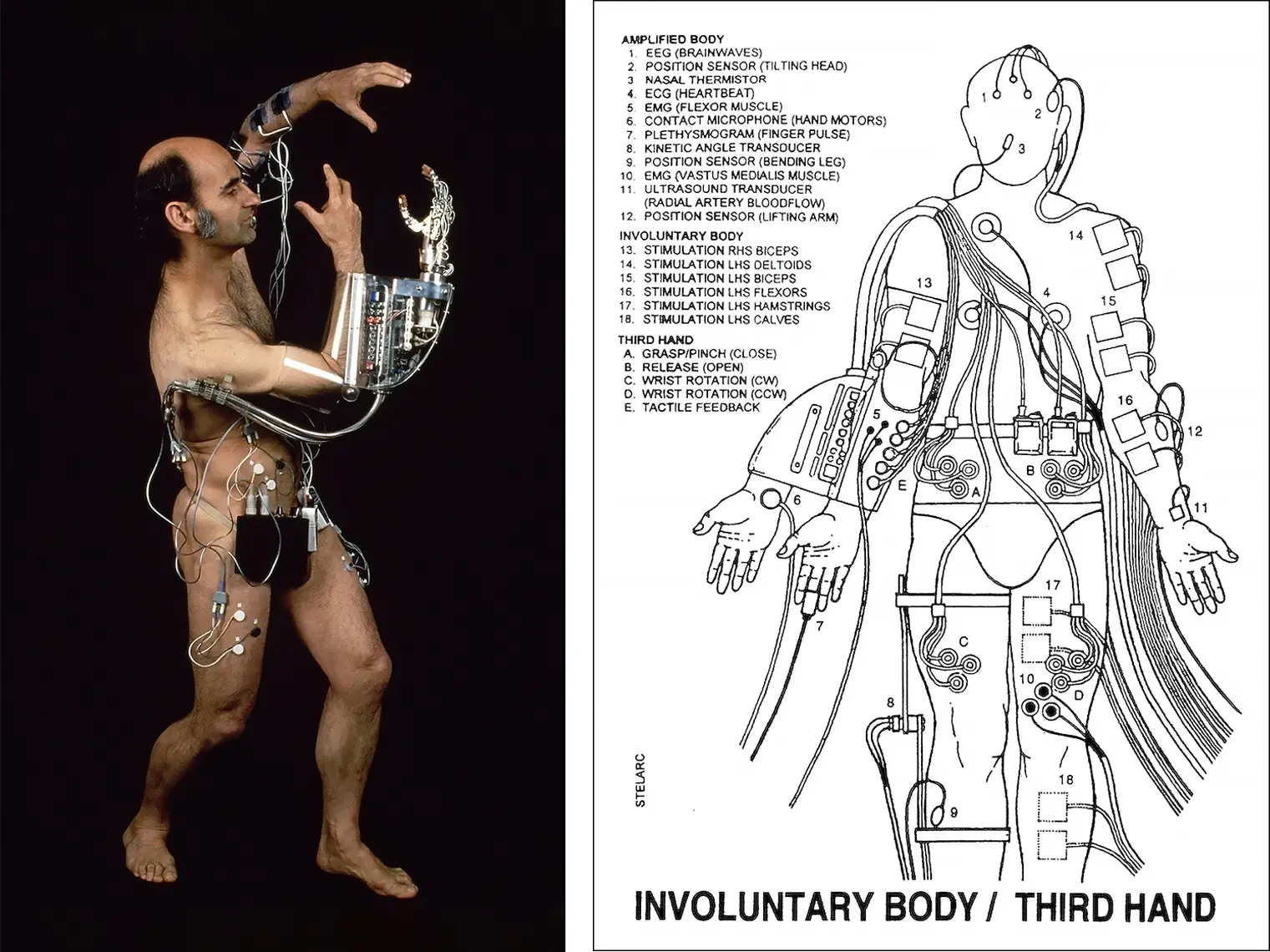

Clearly then, technology is fundamental to who we are; but more than that, it’s a mistake to see it as a mere “tool” or “resource,” for the same reason that it’s wrong to consider nature an “externality.” The Australian performance artist Stelarc put this beautifully in an interview about his work in 2002:

The body has always been a prosthetic body. Ever since we evolved as hominids and developed bipedal locomotion, two limbs became manipulators. We have become creatures that construct tools, artefacts and machines. We’ve always been augmented by our instruments, our technologies. Technology is what constructs our humanity; the trajectory of technology is what has propelled human developments. I’ve never seen the body as purely biological, so to consider technology as a kind of alien other that happens upon us at the end of the millennium is rather simplistic. 9

In other words, with our use of fire, clothes, medicines, and so on, technology has always been part of us, not an “other.” Long before modern AI, Donna Haraway made a similar point in even more striking terms:

The machine is not an it to be animated, worshipped, and dominated. The machine is us, our processes, an aspect of our embodiment. We can be responsible for machines; they do not dominate or threaten us. We are responsible for boundaries; we are they. 10

This is why the idea that robots are “taking our jobs,” as if robots are some kind of alien invading force, doesn’t make a lot of sense. Robots aren’t an “other” that competes with us—like any technology, they’re part of us. They may not exactly be alive according to most definitions, 11 but they grow out of civilization the same way hair and nails grow out of a living body. They’re part of humanity… and we’re partly machine.

Granted, this may seem like cold comfort to human seasonal laborers who lose their livelihood to robotic fruit pickers that can, in Doug Nimz’s words, 12 “run for 24 hours a day [when] conditions are fit”—perhaps picking the fruit at peak ripeness with a flurry of precision manipulators, operating in an eerily lit greenhouse with an unbreathable high-CO2 atmosphere.

At issue is not the machine, but inequality among human beings. Too many of us haven’t understood yet that we’re also interdependent. We’re all in it together; we need to share our gains as we develop in order for the center to hold. By “othering” the robot and thinking of it as a competitor that has won a zero-sum game of efficient fruit picking, we take our eyes off the real problem: the person picking the fruit had no stake in the success of the farm, let alone the survival of the planet, and is considered disposable by the farm’s owners and by society when no longer “useful” at that job. When a government engages in mass surveillance of its citizenry, a similar breach in solidarity takes place, whether the mechanism involves ubiquitous networks of human informants (as in communist East Germany) or ubiquitous networks of AI-enabled cameras (as in Xinjiang). 13

This is the situation we live in today: alienation. It implies that the human citizen or laborer was already being treated like a non-person—that is, like a machine. Conversely, we’re in the untenable position of “othering” the machine because we were already in the untenable position of “othering” each other.

The underlying inequalities cut in well-documented ways across lines of race, ethnicity, gender, and class. In the American context, the owners of large farms, like big businesses in many sectors of the American economy, tend to be older, white, and male. 14 They may be worried about cultural upheaval or having their guns taken away, but they’re not generally the ones worried about robots taking their jobs. On the contrary, they’re the ones installing and upgrading those robotic systems, to improve the profitability of their farms. (In fairness, they may feel they have little choice to remain competitive, if all the neighbors are upgrading.) It’s the largely Hispanic farm laborers whose livelihoods are threatened. Cycles like this lead to amplification of inequalities over time, and the hardening of identity groups in the face of struggle and grievance.

Of such a struggle in the coal mines of Harlan County, Kentucky, in the 1930s, songwriter-activist Florence Reece sang,

Which side are you on?

Which side are you on?

They say in Harlan County,

There are no neutrals there.

You’ll either be a union man,

Or a thug for J.H. Blair.

Oh, workers can you stand it?

Oh, tell me how you can.

Will you be a lousy scab,

Or will you be a man?

Eventually, union solidarity worked, and not just for coal miners (or men). The labor movement secured important rights and dignities many of us take for granted today; we can thank those organizers for the five day, 40-hour work week.

Organizing relies on the creation of anonymous identities, as described in the Introduction; that’s why popular movements like the Harlan County worker’s strike have historically only taken off once urbanization is in full swing. Peasant farmers in agricultural societies are too spread out to create concentrated “people power,” especially without modern communication technologies. When workers gather at the coal mine or in the factory, though, the situation changes. Even if initially underpaid and overworked, they can form an anonymous identity and take collective action.

Commenting on an earlier people’s movement during the Industrial Revolution, radical British orator John Thelwall wrote,

[M]onopoly, and the hideous accumulation of capital, in a few hands, […] carry, in their own enormity, the seeds of cure. Man is, by his very nature, social and communicative—proud to display the little knowledge he possesses, and eager, as opportunity presents, to encrease his store. Whatever presses men together, therefore, though it may generate some vices, is favourable to the diffusion of knowledge, and ultimately promotive of human liberty. Hence every large workshop and manufactory is a sort of political society, which no act of parliament can silence, and no magistrate disperse. 15

Seen this way, unions, collective bargaining, and labor politics are social technologies, and as always, the spark of an idea requires a sufficient concentration of people to ignite. The function of such social technologies is to more equitably distribute the wealth generated by efficiencies of scale.

The trouble, though, is that the adversarial nature of class struggle combines in-group solidarity with out-group othering. It implies that life is zero-sum, us-versus-them. It creates a binary identity around being either a “worker” or an “owner,” with neither side necessarily incented to do the right thing from a planetary perspective. Should coal mining still be practiced today? If we believe in the importance of efficiency, technology, and environmental regulation for continued human survival on Earth, a traditional union whose mission is to protect labor from disruption will be pitted against this greater goal. On the other hand, traditional owners who instrumentalize their human “workforce” have no incentive to redistribute the economic benefits of efficiency—or to worry about the planet.

So, it turns out that we’re all members of the precariat: a social class whose survival is precarious at every level, lacking in physical, psychological, or economic security—not because we lack the means for everyone to thrive, but because we lack solidarity at the needed scale. In an interdependent world, we can only achieve safety through mutual care, empathy, and trust. The overarching challenge of our century is to become a very big “we,” including all humans, our technologies, and the plants, and animals, and every other lifeform on the planet. They are not just our kin, but our self. We’ll need a planet-sized umbrella identity.

Applebaum, Twilight of Democracy, 180, 2020.

See Chapter 20.

See the first interlude.

Lovelock, Novacene, 70, 2019.

For instance: philosopher and polymath Justin Smith-Ruiu has written, “AI is […] a massive kick in the balls to humanity. I will continue to kick back for as long as I am alive—not in combat against the “pathetic fallacy” [the attribution of human feelings and responses to inanimate things or animals], the very notion of which I reject, but in defense of the ecumene of true beings against the encroachment of spurious ones.” Smith-Ruiu, “Cull the Robo-Dogs, Cherish the Dirt-Clods: On AI, the Pathetic Fallacy, and the Boundaries of Community,” 2023.

See Chapters 12 and 13.

See Chapters 18 and 19.

See Chapter 16.

Zylinska and Hall, “Probings: An Interview with Stelarc,” 2002.

Haraway, “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century,” 1991.

Although by a more expansive definition of life, they are; see Walker, “AI Is Life,” 2023.

See Chapter 20.

See Chapter 14.

In other countries, equivalent majoritarian biases apply.

Thelwall, The Rights of Nature Against the Usurpations of Establishments, 1796.

Rushkoff, Survival of the Richest, 2022.